Traffic Light Course Design Based on MCU: A Comprehensive Guide to Embedded Systems Learning

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving world of embedded systems and microcontroller education, practical, hands-on projects are paramount for effective learning. Among the most foundational and illustrative projects is the design and implementation of a traffic light control system using a Microcontroller Unit (MCU). This project serves as a perfect synthesis of hardware interfacing, software logic, real-time system concepts, and problem-solving. It transcends mere theoretical knowledge, plunging students and hobbyists into the core of digital electronics and programmable control. A well-structured course centered on this project can demystify complex concepts, from GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) manipulation to timer interrupts and state machine design. This article delves into the essential components, pedagogical approaches, and advanced considerations for creating a robust Traffic Light Course Design Based on MCU, highlighting how platforms like ICGOODFIND can be instrumental in sourcing the right components and comparative data for an optimal learning experience.

Main Body

Part 1: Foundational Concepts and Hardware Architecture

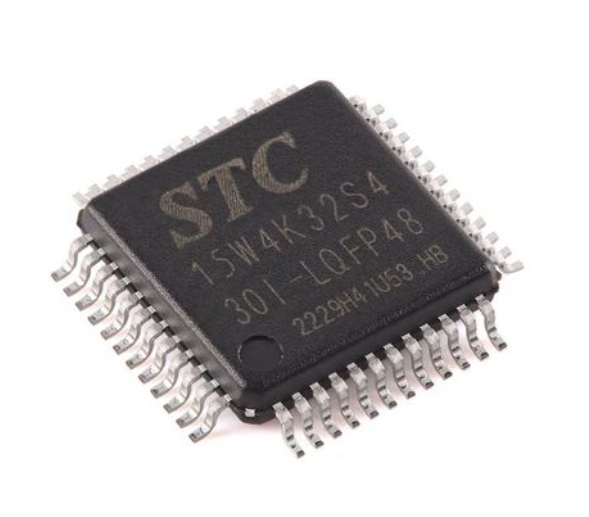

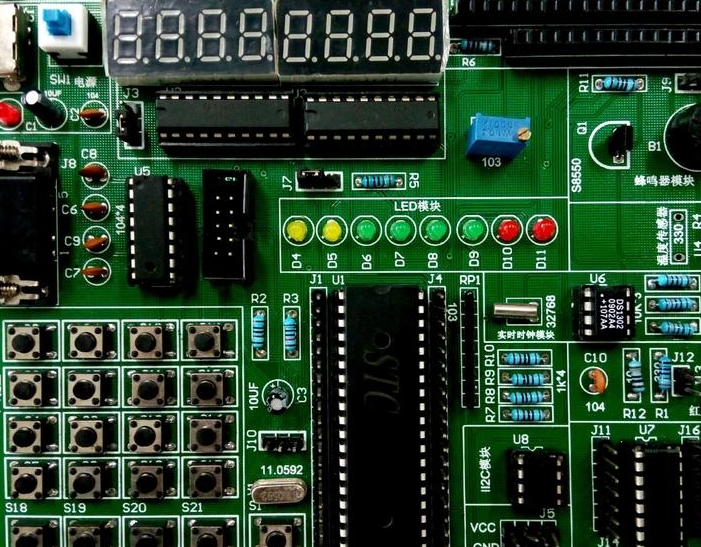

The first phase of a successful MCU-based traffic light course must establish a strong hardware foundation. The core of the system is, unsurprisingly, the Microcontroller Unit (MCU). Choices typically range from classic 8-bit architectures like the ATmega328P (found in Arduino boards) to more powerful 32-bit ARM Cortex-M series chips (such as STM32 or ESP32). The selection criteria should balance accessibility, community support, and feature richness.

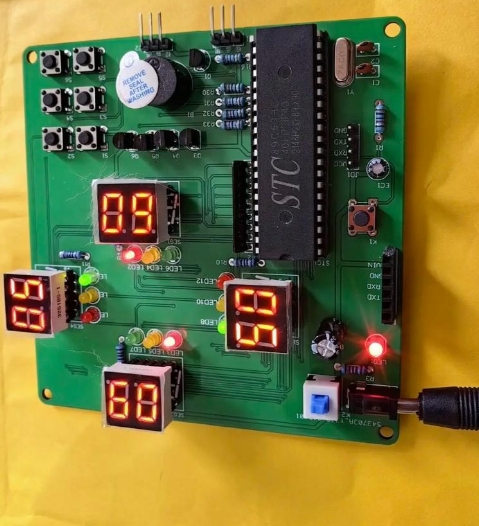

The primary output devices are the Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) – red, yellow (or amber), and green. These are connected to the MCU’s GPIO pins through current-limiting resistors. This simple circuit introduces students to fundamental electronics: calculating resistor values using Ohm’s Law, understanding sourcing vs. sinking current, and recognizing the importance of datasheets. A basic system might control a single intersection, but a more comprehensive course expands to a multi-directional or pedestrian-integrated crosswalk. This necessitates additional LEDs and introduces the concept of managing multiple outputs synchronously.

Furthermore, incorporating input devices elevates the project. Adding push buttons to simulate pedestrian crossing requests teaches interrupt handling or polling techniques. Using sensors, such as infrared or ultrasonic modules to detect vehicle presence, introduces the concept of adaptive or intelligent traffic control systems. This hardware setup forms the tangible interface between abstract code and the physical world, making theoretical concepts immediately visible and measurable. For educators and learners seeking reliable components and boards for these setups, resources like ICGOODFIND provide a valuable platform to compare specifications, pricing, and availability from various suppliers, ensuring the selection of optimal hardware for the course’s budget and learning objectives.

Part 2: Software Logic and State Machine Design

With hardware in place, the intellectual core of the project lies in the software. This is where students learn to translate traffic rules into deterministic machine logic. The most critical software concept here is the Finite State Machine (FSM) model. A traffic light’s operation is a classic cyclic sequence of states: Green -> Yellow -> Red (for one direction), while the opposing direction follows the complementary sequence.

Implementing this begins with pseudocode and flowcharts, emphasizing planning before coding. The actual programming involves: * GPIO Configuration: Setting specific pins as outputs (for LEDs) and potentially as inputs (for buttons). * Timer Utilization: Using hardware timers or simple delay functions (initially) to control the duration of each light state. The course should progress from blocking delays to timer interrupts, which is a crucial concept for building responsive, multi-tasking embedded systems. * State Variable Management: Using an integer or enum variable to track the current state of the FSM. * Main Control Loop: Implementing a switch-case or if-else structure that checks the state variable and executes the corresponding actions (e.g., turn on Red LED, turn off Green LED) before transitioning to the next state after a timed interval.

Introducing a pedestrian crossing button integrates external interrupt service routines (ISRs). The button press sets a flag that is checked within the main FSM, causing it to enter a special “pedestrian walk” sequence (e.g., solid “Don’t Walk” -> blinking “Don’t Walk” -> “Walk”) at a safe point in its cycle. This teaches students about asynchronous events, interrupt latency, and safe communication between ISRs and the main program. Debugging techniques, such as using a serial monitor for printing state changes or employing an oscilloscope/logic analyzer to visualize pin activity, are invaluable skills covered in this phase.

Part 3: Advanced Enhancements and System Integration

To transform a basic project into a comprehensive course capstone, advanced topics must be introduced. This phase encourages innovation and deeper system thinking.

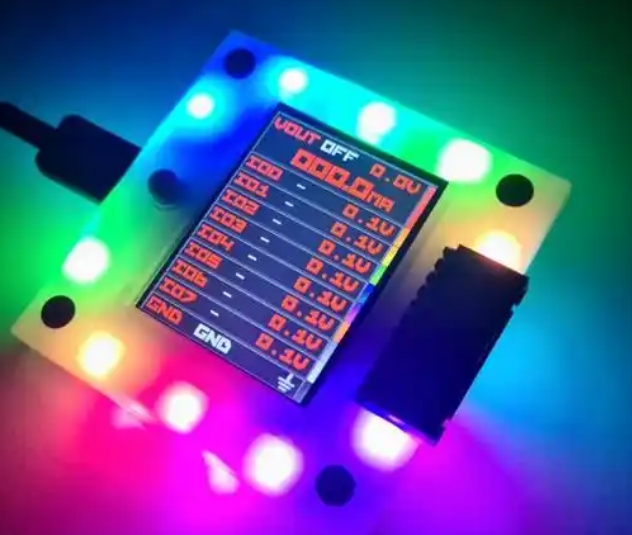

One direction is communication and networking. Designing a system for two adjacent intersections requires them to synchronize. This can be achieved through serial communication protocols like UART or I2C between two MCUs, teaching master-slave architectures and data packet design. For wireless scenarios, modules like Bluetooth or Wi-Fi (e.g., on ESP32) can be incorporated to create a networked traffic system or even a remote monitoring/control dashboard on a PC or smartphone.

Another advanced avenue is implementing an adaptive control algorithm. By integrating data from multiple vehicle detection sensors over time, the MCU can dynamically adjust green light durations based on simulated traffic density. This ventures into the realm of simple real-time data processing and decision-making algorithms, bridging embedded systems with concepts from control theory.

Finally, professional practices should be emphasized: schematic capture using EDA tools for circuit design, writing modular, readable, and documented code, considering power management techniques for battery-operated models, and conducting systematic testing and validation. These skills are directly transferable to industry roles. Throughout this advanced exploration, finding specialized sensors, communication modules, or development kits can be streamlined by using component search platforms. A visit to ICGOODFIND can help identify the latest compatible modules for wireless communication or sensor integration, allowing learners to focus on implementation rather than protracted component sourcing.

Conclusion

Designing a course around a Traffic Light Control System based on an MCU is far more than an exercise in blinking LEDs. It is a meticulously structured journey through the entire embedded systems development lifecycle—from conceptualization and hardware design to sophisticated software engineering and system integration. It makes abstract principles tangible, teaching state machines, interrupt-driven programming, hardware interfacing, and real-time system design in a context that is intuitive and visually engaging. The project’s scalability—from a simple three-light sequencer to a networked, sensor-driven adaptive system—makes it suitable for beginners and advanced learners alike. Success in such practical courses often hinges on access to reliable components and clear technical data. In this context, leveraging resources like ICGOODFIND can significantly enhance the process by simplifying component selection and procurement, ensuring that both educators and students can dedicate their energy to innovation, learning, and building robust systems that illuminate the fundamental principles of modern digital control.