The Ultimate Guide to MCU Electronic Clocks: Design, Function, and Applications

Introduction

In the intricate world of modern electronics, the humble clock remains a fundamental component, orchestrating the precise timing of operations in countless devices. At the heart of many contemporary timekeeping solutions lies the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) Electronic Clock. This sophisticated integration of hardware and software has revolutionized how we measure, display, and utilize time, moving far beyond simple alarm functions. An MCU-based electronic clock represents a convergence of precision timing circuits, programmable intelligence, and versatile input/output capabilities. From smart home appliances and industrial automation to wearable tech and automotive systems, these intelligent timekeepers are ubiquitous. This article delves deep into the architecture, operational principles, and vast application landscape of MCU electronic clocks, highlighting why they have become the preferred choice for engineers and developers. For professionals seeking specialized components or inspiration for their next project, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer invaluable resources to source the ideal MCU and peripheral circuits for advanced clock designs.

Main Body

Part 1: Core Architecture and Working Principle of an MCU Electronic Clock

The functionality of an MCU electronic clock hinges on a harmonious interplay between its hardware components and the embedded software that drives them. Understanding this architecture is key to appreciating its reliability and versatility.

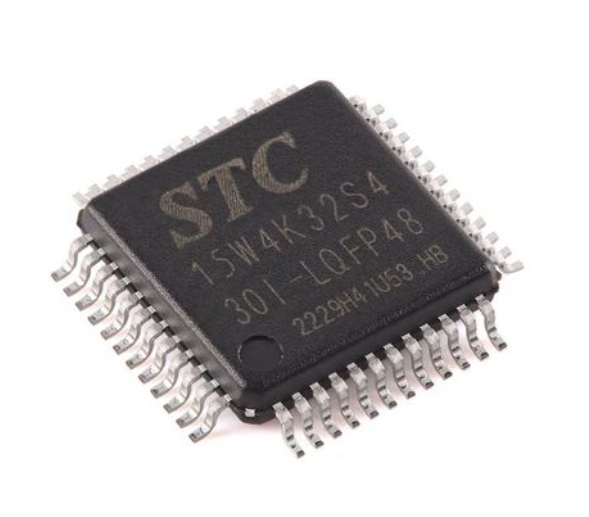

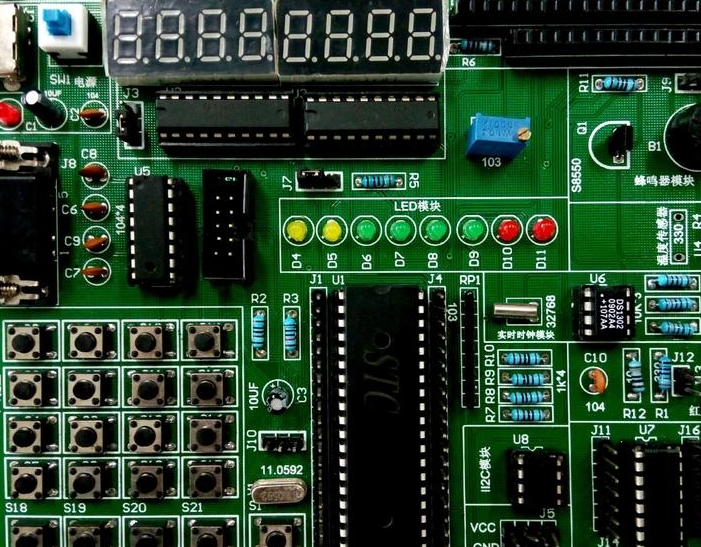

Hardware Foundation: The primary hardware component is, unsurprisingly, the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) itself. This is a compact integrated circuit designed to govern a specific operation. For clock applications, an MCU with a built-in Real-Time Clock (RTC) module is often preferred, though external RTC chips (like the DS1307) can be interfaced via I2C or SPI protocols for higher precision. The RTC is crucial as it continues to keep time using a backup battery (often a coin cell) even when the main power is disconnected.

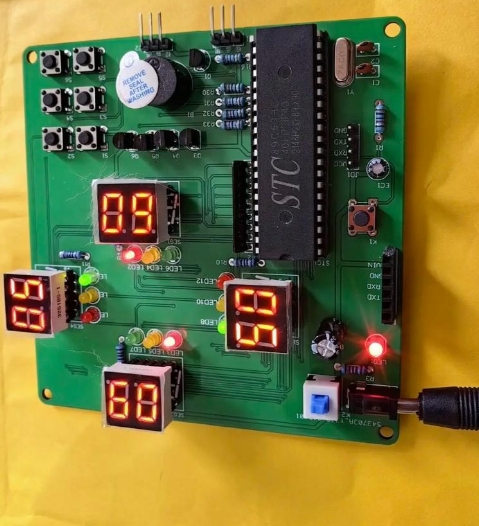

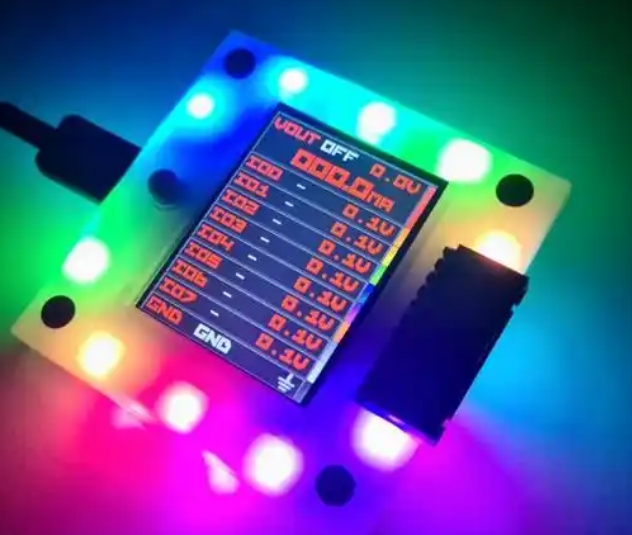

Supporting the MCU are several critical components: * Time Base Oscillator: This is typically a 32.768 kHz quartz crystal. This specific frequency is chosen because it is a power of two (2^15), making it easy for the MCU’s digital counters to divide down to exactly one pulse per second (1Hz), the fundamental unit of timekeeping. * Display Interface: The time data processed by the MCU must be presented to the user. Common displays include 7-segment LED displays (multiplexed to save pins), liquid crystal displays (LCDs), or even OLED panels for more graphical output. The MCU drives these displays directly or through driver ICs. * Input Interface: User interaction is facilitated through inputs like tactile buttons, rotary encoders, or touch sensors, allowing for time setting, alarm configuration, and mode changes. * Power Supply System: A regulated power supply circuit ensures stable voltage for the MCU and active components, while a backup battery circuit is essential for the RTC to maintain time during power outages.

Software & Firmware Intelligence: The hardware is inert without software. The firmware embedded in the MCU’s flash memory performs several core tasks: 1. Initialization: Configuring internal clocks, I/O pins, timers, and communication peripherals (like I2C for an external RTC) upon startup. 2. Timekeeping Algorithm: Reading counts from the RTC module or internal timers triggered by the crystal oscillator. It processes these counts into human-readable units: seconds, minutes, hours, day, date, month, and year, accounting for leap years. 3. Display Driver Routine: Continuously updating the display with current time data. In multiplexed LED designs, this involves a rapid scanning routine that creates the illusion of all segments being lit simultaneously. 4. Input Polling & Debouncing: Constantly checking the state of input buttons using efficient algorithms to filter out electrical noise (debouncing) and execute precise user commands like “hour advance.” 5. Alarm & Interrupt Handling: Comparing current time with user-set alarm times and triggering outputs (like sounding a buzzer or activating a relay) when a match occurs. This is often managed through interrupt service routines for efficiency.

The true power of an MCU-based design lies in this programmability. Adding features like multiple time zones, countdown timers, temperature display (with a sensor), or network synchronization becomes a matter of firmware development rather than a complete hardware redesign.

Part 2: Key Advantages Over Traditional Clock Mechanisms

The adoption of MCU electronic clocks over older mechanical or discrete digital logic designs is driven by several compelling advantages that impact performance, cost, and functionality.

Unmatched Precision and Stability: While mechanical clocks are susceptible to wear and environmental changes, an MCU clock’s accuracy is determined by the frequency stability of its quartz crystal oscillator. These oscillators exhibit minimal drift, often losing or gaining only a few seconds per month. Furthermore, software calibration routines can be implemented to correct even this minor drift, achieving long-term accuracy that mechanical systems cannot match.

Remarkable Flexibility and Feature Integration: This is arguably the most significant advantage. The functionality of an MCU clock is defined by its software. With firmware updates, a single hardware platform can serve as a simple desk clock, a complex industrial timer with multiple relay outputs, or a sports stopwatch. Features like programmable alarms (multiple, recurring), calendar functions until year 2099, daylight saving time auto-adjustment, and various display formats can be integrated seamlessly. This flexibility future-proofs designs and allows for mass customization.

Superior Power Efficiency: Modern MCUs are designed with power-saving at their core. In clock applications, the MCU can spend most of its time in a low-power “Sleep” or “Idle” mode, waking up only briefly (e.g., once per second) to update registers and the display. The dedicated low-power RTC modules can run for years on a small backup battery. This makes MCU clocks ideal for battery-powered portable devices, such as travel clocks or embedded timers in remote sensors.

Cost-Effectiveness in Mass Production and Enhanced Reliability: A single MCU replaces numerous discrete logic chips (counters, decoders, latches), reducing component count on the printed circuit board (PCB). This simplifies manufacturing, lowers assembly costs, minimizes physical size, and enhances overall system reliability by reducing potential points of failure. There are no moving parts to wear out as in mechanical clocks.

Part 3: Diverse Applications Across Industries

The versatility of MCU electronic clocks has led to their proliferation across virtually every sector of technology.

Consumer Electronics: This is the most visible domain. MCU clocks are integral to: * Home Appliances: Ovens, microwaves, washing machines, coffee makers—all rely on programmable timers for automated operation. * Personal Devices: Digital wristwatches (including smartwatches), alarm clocks with radio/smartphone integration. * Multimedia Systems: Televisions set-top boxes record programs based on precise internal clocks.

Industrial Automation and Control: Here, reliability and precision are paramount. * Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs): Use internal clocks to timestamp events sequence operations and schedule machine cycles. * Data Loggers: Precisely timestamp sensor readings (temperature pressure) for analysis. * Process Timers: Control duration of chemical reactions mixing cycles or conveyor belt operations in manufacturing.

Automotive Systems: Modern vehicles contain dozens of MCUs many with timing functions. * Instrument Clusters: Digital speedometers and trip computers with date/time display. * Infotainment Systems: Clock navigation ETA calculations. * Event Recorders & Diagnostics: Timestamp fault codes for maintenance.

Telecommunications & Networking: Synchronization is critical in this field. * Network Time Protocol (NTP) Clients: Devices like routers use internal RTCs as a time-keeping base before synchronizing with internet time servers. * Base Stations: Require extremely precise timing for signal transmission coordination.

For engineers designing solutions in any of these fields finding the right balance of MCU performance peripheral set power consumption and cost is vital. This is where component discovery platforms prove essential. A resource like ICGOODFIND can streamline the search allowing developers to efficiently compare specifications from various manufacturers source reliable components and accelerate the development cycle for their next-generation MCU clock application.

Conclusion

The MCU electronic clock stands as a testament to how embedded intelligence can transform a basic function into a cornerstone of modern technology. By merging the unwavering accuracy of quartz crystal oscillation with the boundless flexibility of programmable firmware it has evolved from a simple time-telling device into a critical subsystem enabling automation synchronization and smart functionality across global industries Its advantages in precision integration power efficiency and reliability make it an indispensable design choice As technology progresses towards greater interconnectivity in the Internet of Things (IoT) era the role of the intelligent synchronized MCU-based clock will only grow more central For innovators continuing to push boundaries in electronic design leveraging comprehensive resources to select optimal components remains a key step in bringing precise timely and innovative products to market.