MCU Assembly Language Tutorial: A Beginner’s Guide to Low-Level Programming

Introduction

In the world of embedded systems and microcontroller programming, high-level languages like C and C++ often take center stage. However, beneath the abstraction layers lies the foundational language of the hardware itself: Assembly Language. Mastering MCU (Microcontroller Unit) Assembly Language is not just an academic exercise; it is a powerful skill that provides unparalleled control over hardware resources, enables optimization for critical performance and power constraints, and offers deep insight into the machine’s true operation. This tutorial is designed for beginners with basic programming knowledge, aiming to demystify assembly language and provide a practical starting point for your journey into low-level microcontroller programming. By understanding the core concepts presented here, you will build a solid foundation for writing efficient, compact, and powerful code for resource-constrained devices.

Part 1: Understanding the Core Concepts of MCU Assembly

Before writing your first line of assembly code, it’s crucial to grasp the environment in which it operates. Unlike high-level languages, assembly provides a nearly one-to-one correspondence with the machine code instructions executed by the microcontroller’s Central Processing Unit (CPU).

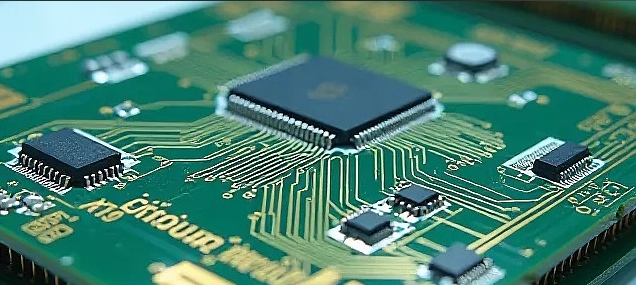

At its heart, an MCU consists of key components like the CPU, memory (Flash for program storage, RAM for data), and various peripherals (timers, communication interfaces). The CPU contains registers—small, ultra-fast storage locations directly within the processor. These registers are the primary workspace for assembly operations. Common register types include the Program Counter (PC), which points to the next instruction to execute, the Stack Pointer (SP), which manages the call stack, and general-purpose registers (like R0-R31 in many architectures) for data manipulation.

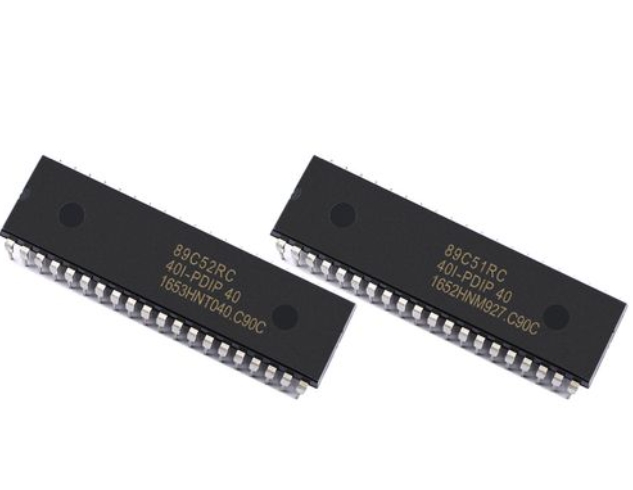

Assembly language is specific to a processor’s architecture. The two most common families in the MCU world are ARM Cortex-M (using ARM Thumb/Thumb-2 instruction sets) and various AVR cores (found in Arduino boards like the ATmega328P). While their syntax differs, the fundamental concepts remain consistent. An assembly program is essentially a sequence of mnemonics—human-readable abbreviations for instructions (like MOV for move, ADD for addition)—that operate on registers or memory addresses.

The primary advantage of assembly is direct hardware control and deterministic execution. You know precisely how many clock cycles each instruction takes, allowing for exact timing-critical operations. Furthermore, you can write extremely size-efficient code, stripping away all overhead, which is vital for devices with limited Flash memory. To effectively learn and experiment, you will need a development environment consisting of an assembler (like avr-as for AVR or arm-none-eabi-as for ARM) to convert your source code into machine code, a hardware programmer/debugger, and a target development board or simulator.

Part 2: Essential Instructions and Programming Structure

Let’s dive into practical programming by examining common instruction types and program flow. We’ll use generic examples inspired by common architectures.

Data Transfer Instructions form the backbone of most programs. The MOV (Move) instruction copies data from a source to a destination, typically between registers. For example, MOV R1, R0 copies the contents of register R0 into R1. To work with memory, load (LDR/LD) and store (STR/ST) instructions are used. For instance, LDR R2, [R3] might load R2 with data from the memory address held in R3.

Arithmetic and Logic Instructions perform calculations. Core instructions include ADD, SUB (subtract), AND, OR, and EOR (exclusive OR). These often operate on registers: ADD R0, R1, R2 could mean R0 = R1 + R2. The compare (CMP) instruction is vital; it subtracts two values without storing the result but sets status flags in the CPU’s status register based on the outcome (zero, negative, carry). These flags control program flow.

Control Flow Instructions direct the execution path. Unconditional jumps (B or JMP) move execution to a label elsewhere in the code. Conditional branches use status flags. After a CMP R0, R1, you might use BEQ Label (Branch if EQual, i.e., if Z flag is set) to jump only if R0 equaled R1. Other conditions include BNE (Branch if Not Equal), BGT (Branch if Greater Than). Subroutine calls use CALL/BL (Branch with Link) to jump to a function, saving the return address. The RET instruction returns from it.

A basic program structure includes: 1. Initialization: Set up the stack pointer, clear registers. 2. Main Loop: The primary application logic. 3. Subroutines/Functions: Reusable blocks of code. 4. Data Section: Define constants and variables in memory.

Here’s a conceptual snippet that adds two numbers stored in memory and stores the result:

LDR R0, =ValueA ; Load address of ValueA into R0

LDR R1, [R0] ; Load the actual data from that address into R1

LDR R0, =ValueB

LDR R2, [R0] ; Load ValueB into R2

ADD R3, R1, R2 ; R3 = R1 + R2

LDR R0, =Result

STR R3, [R0] ; Store result back to memory

Loop: B Loop ; Infinite loop to stop execution

ValueA: .word 0x15 ; Define data in memory

ValueB: .word 0x27

Result: .space 4 ; Reserve 4 bytes for result

Part 3: Practical Applications and Advanced Techniques

Moving beyond basics, assembly shines in specific real-world scenarios where its precision is paramount.

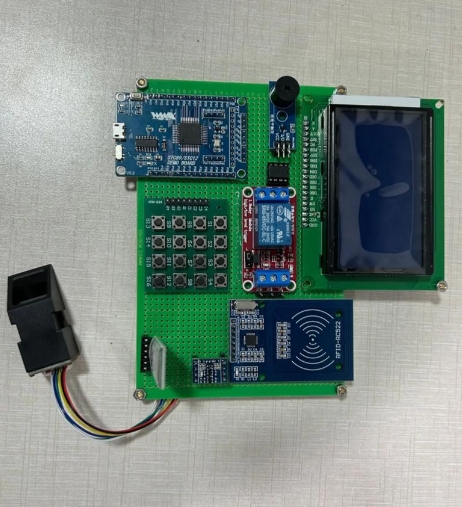

Direct Peripheral Control is a major application. Consider blinking an LED connected to a specific GPIO pin. In a high-level language, you might call digitalWrite(). In assembly, you directly manipulate the microcontroller’s hardware registers: 1. Configure the pin as an output by writing a ‘1’ to the correct bit in the Data Direction Register (DDR). 2. Drive the pin high or low by writing to the Port Output Register.

This involves using bit manipulation instructions like ORR (OR Register) to set bits and BIC (Bit Clear) to clear them without affecting others—a technique known as “read-modify-write.”

Writing time-critical delay loops is another classic use case. Since you know each instruction’s cycle count (from the datasheet), you can create precise software delays:

Delay: MOV R5, #DELAY_COUNT ; Load loop counter

Loop_Delay: SUBS R5, R5, #1 ; Decrement counter & set flags

BNE Loop_Delay ; Branch back if not zero

RET ; Return after exact delay

This provides deterministic timing without relying on hardware timers.

For more complex tasks like Interrupt Service Routines (ISRs), assembly offers optimal performance. An ISR must save the CPU context (registers), service the interrupt quickly, restore context, and return using a special instruction like RETI. Writing this in assembly minimizes latency.

As your programs grow, embrace structured programming: use clear labels for subroutines and data sections (main_loop, delay_ms, data_table). Comment liberally—assembly code can become opaque quickly. A comment should explain why an operation is done more than what it does (; Clear watchdog timer before timeout reset vs. ; Write 0x5A to WDTCR).

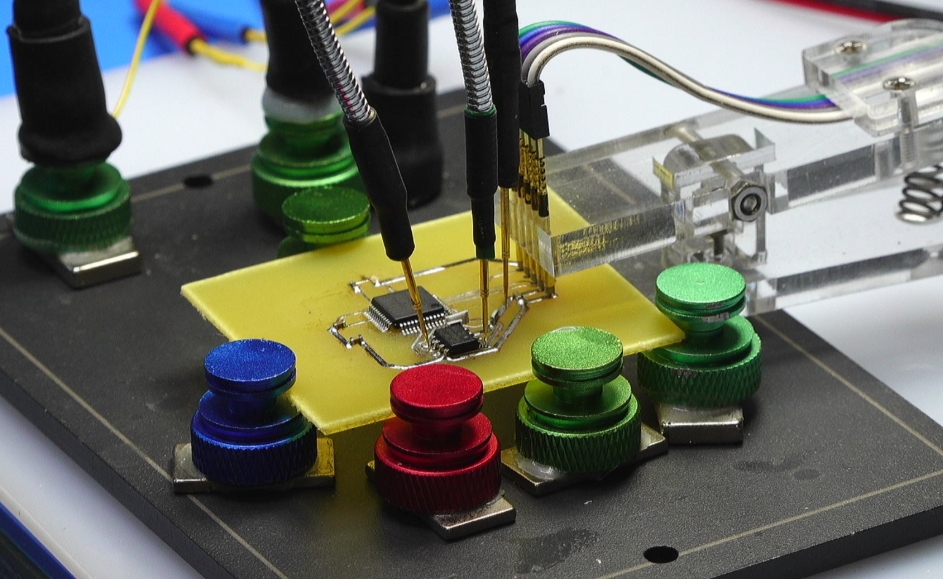

Finally,debugging requires a methodical approach. Use a simulator or hardware debugger to single-step through instructions while monitoring register and memory changes—a process that reinforces your understanding of program flow at its most fundamental level.

Conclusion

Embarking on the journey of learning MCU Assembly Language opens a door to truly understanding how software interacts with silicon. While it presents challenges in readability and development speed compared to high-level languages,its unparalleled efficiency,direct hardware mastery,and educational value make it an indispensable tool for serious embedded systems developers. You begin to think like the machine,fostering skills that will improve your code even in higher-level languages.Start with simple tasks like GPIO control and timing loops on a common platform like AVR or ARM Cortex-M.Use simulators extensively before moving to hardware,and always consult your MCU’s datasheet—it is your ultimate guide.Remember,the goal isn’t always to write entire applications in assembly,but to know how to wield it when performance,margin,and control are non-negotiable.For developers seeking curated resources,tools,and deeper dives into efficient embedded programming practices across various architectures,a platform like ICGOODFIND can serve as a valuable aggregator,saving significant research time by highlighting quality tutorials,toolchains,and community insights.