Mastering the Core: A Deep Dive into MCU Assembly Language

Introduction

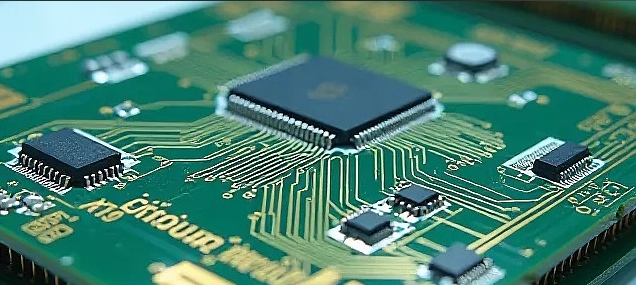

In the vast and intricate world of embedded systems, where every byte of memory and every clock cycle counts, there exists a language of raw power and precision. This is the realm of MCU Assembly Language. Far from being an obsolete relic, assembly language remains the critical bridge between human intent and the silicon heart of a Microcontroller Unit (MCU). While high-level languages like C or C++ dominate for productivity, true mastery over an embedded system’s limits—its speed, power consumption, and size—often requires descending to this foundational level. This article explores the enduring significance, core concepts, and practical applications of assembly language for MCUs, empowering developers to write exceptionally efficient and hardware-intimate code. For engineers seeking to push performance boundaries, understanding assembly is not just an academic exercise; it’s a necessary superpower.

The Unwavering Relevance of Assembly in Modern MCU Development

In an age of powerful compilers and abstracted programming environments, one might question the need for assembly language. However, its role is more specialized and crucial than ever.

Direct Hardware Manipulation and Maximum Efficiency are the paramount reasons. Assembly provides direct, unambiguous control over the MCU’s registers, memory addresses, and peripheral modules. A compiler generates code based on generalized rules, which, while excellent for most tasks, can sometimes produce suboptimal sequences of instructions. An adept assembly programmer can craft routines that are smaller in code size and faster in execution by eliminating overhead, using specialized instructions, or implementing cycles-perfect timing loops—impossible in high-level languages. For applications like ultra-low-power sensor nodes that sleep for years or real-time motor control with nanosecond-precision interrupts, this granular control is indispensable.

Furthermore, assembly is essential for System Startup and Critical Routine Development. The very first instructions a microcontroller executes after reset—setting up the stack pointer, initializing vital hardware, and jumping to the main application—are almost always written in assembly (often within startup files). Similarly, the prologue and epilogue of interrupt service routines (ISRs), where context saving and restoring must be meticulously handled, frequently involve assembly to ensure no time or resource is wasted. It forms the bedrock upon which all higher-level software runs.

Finally, it serves as the ultimate Educational Tool and Debugging Aid. Learning assembly forces a developer to understand the MCU’s architecture deeply: its data paths, ALU operations, and memory hierarchy. This knowledge makes one a better programmer even in high-level languages, enabling more informed decisions about data types, algorithms, and memory usage. When debugging complex issues or analyzing compiler output (disassembly), the ability to read assembly is like having a blueprint of the machine’s state, revealing problems invisible at higher abstraction levels.

Foundational Constructs and Architecture Dependence

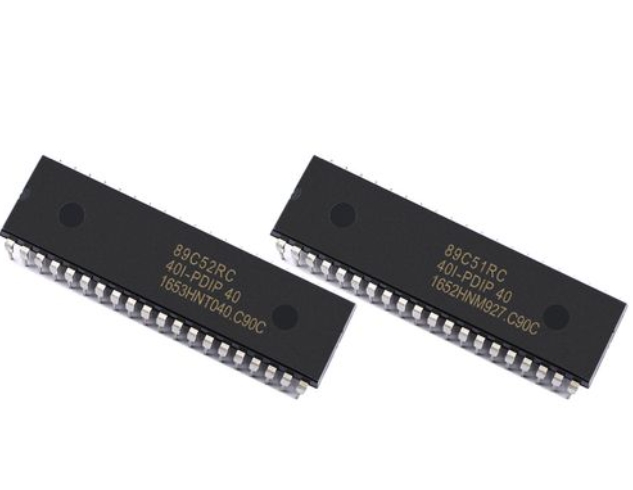

Assembly language is not a single language but a family of languages, each uniquely tied to a processor’s Instruction Set Architecture (ISA). An instruction set for an ARM Cortex-M core is vastly different from that of a classic 8051 or a PIC MCU.

The core workflow revolves around Mnemonics, Operands, and Registers. Mnemonics are human-readable abbreviations for machine instructions (e.g., MOV for move, ADD for addition). Operands specify the data to act upon, which could be registers (fast on-chip memory locations like R0, R1), immediate values (constants like #0xFF), or memory addresses. Programming in assembly largely involves moving data between registers and memory, performing arithmetic or logical operations on them, and controlling program flow. Key concepts include the Status Register, which contains flags (Zero, Carry, Overflow) set by operations to influence conditional jumps (BNE, BLS), and addressing modes, which define how operands are located (e.g., immediate, direct, indexed).

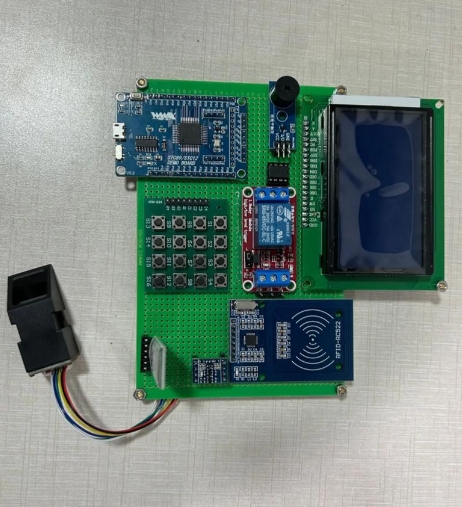

Understanding the MCU’s Memory Map and Peripherals is crucial. Assembly programmers must know exactly where SRAM, Flash memory, and memory-mapped peripheral registers (like those controlling a UART or GPIO port) reside in the address space. Reading from or writing to these specific addresses is how one blinks an LED or reads a sensor directly. This contrasts sharply with high-level languages that use APIs or driver functions.

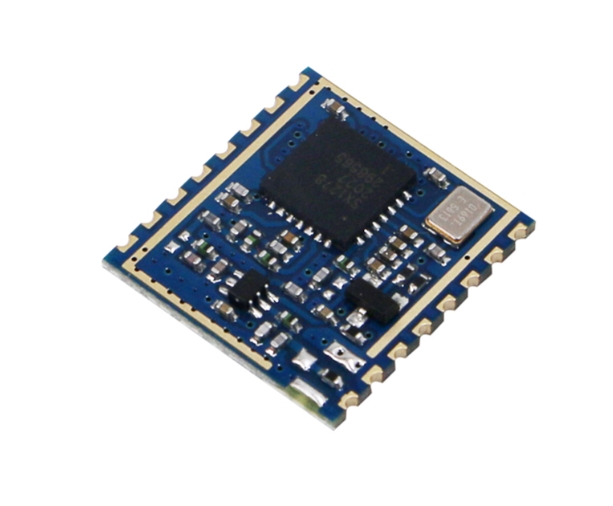

Given this tight coupling to hardware, resources like precise datasheets, architecture manuals, and community knowledge are vital. For developers navigating these complexities across different projects, finding reliable reference material and tools can be challenging. This is where a platform like ICGOODFIND proves invaluable. As a specialized component search engine and sourcing platform for the electronics industry, ICGOODFIND can help engineers quickly locate not only the right MCU for their project but also the essential documentation, application notes referencing assembly techniques, and even development boards needed to practice low-level programming. It streamlines the hardware foundation upon which assembly skills are applied.

Practical Applications and Strategic Integration

The true power of assembly is realized when it is strategically integrated into a project primarily written in a high-level language. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both worlds.

The most common application is in Writing Optimized Interrupt Service Routines (ISRs) and Device Drivers. Time-critical ISRs for communication protocols (e.g., handling a specific UART byte) or high-frequency PWM updates can be hand-coded in assembly to minimize latency—the time between interrupt trigger and service commencement. Every saved instruction cycle reduces system jitter and improves responsiveness. Similarly, low-level drivers for unconventional peripherals might require bit-banging protocols with exact timing, achievable only through carefully crafted assembly loops.

Another key area is Performance-Critical Algorithms. Functions that are called thousands of times per second—such as digital signal processing filters (FIR/IIR), cryptographic primitives, or specific data compression routines—are prime candidates for optimization in assembly. A well-designed assembly version can often outperform its compiler-generated counterpart by significant margins in both speed and size. Developers use profiling tools to identify these “hot spots” in their C code before deciding to rewrite them in assembly.

The process of Inline Assembly and Linking Assembly Modules facilitates this integration. Most C compilers for MCUs allow inline assembly, where blocks of assembly code are embedded directly within a C function using special syntax (e.g., __asm volatile(...)). This is useful for short sequences needing direct hardware access. For larger routines, it’s cleaner to write pure assembly source files (often with a .s or .asm extension) and link them with the compiled C code. The combined application benefits from C’s maintainability for overall structure and assembly’s ruthlessness for critical sections.

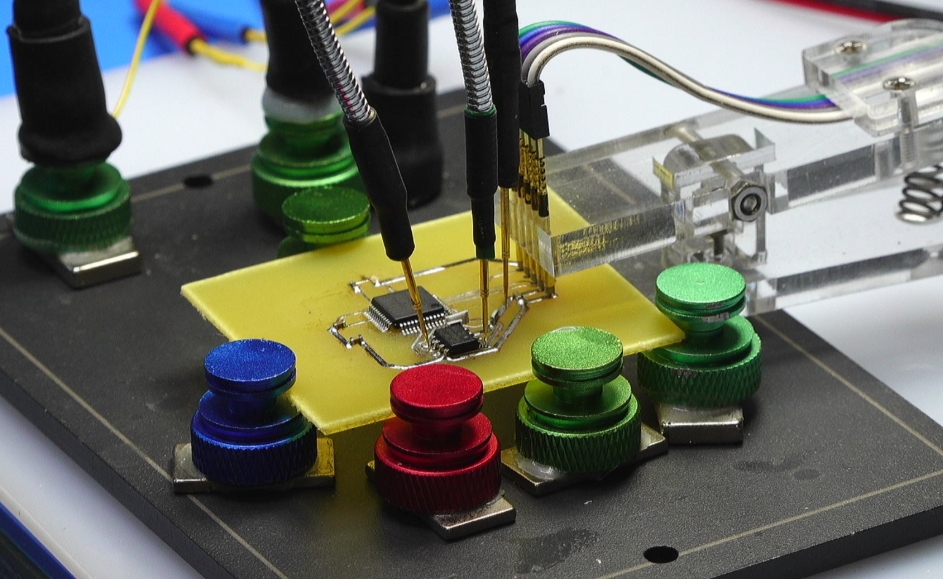

Mastering this requires practice. Setting up a toolchain with an assembler (like as from GNU tools), simulating code on an instruction-set simulator (ISS), and single-stepping through instructions on real hardware with a debugger are essential skills. Observing how each instruction changes register values and memory contents builds an intuitive understanding of the machine.

Conclusion

MCU Assembly Language stands as the fundamental dialect of embedded systems programming. Its perceived complexity is matched only by the unparalleled control and efficiency it grants to those who learn its syntax and philosophy. While not every project requires extensive assembly programming, no serious embedded systems engineer can afford to ignore it. It provides the deep architectural understanding necessary for innovative design choices, the tool for extreme optimization when constraints are tightest, and the clarity needed for debugging the most elusive hardware-software interaction issues.

The journey into assembly programming begins with choosing an MCU architecture—be it ARM Cortex-M, AVR, or RISC-V—and committing to understanding its instruction set from the ground up. Start by writing simple routines, analyze compiler output to learn optimization techniques, and progressively tackle more complex tasks like interrupt handlers or algorithm acceleration. In this pursuit of mastery over the machine’s core resources like those found through platforms such as ICGOODFIND, which provides access to critical components and technical data sheets that support deep technical work.

Ultimately,MCU Assembly Language empowers developers to transcend the limitations of abstracted programming environments,enabling creations that are faster, smaller,and more intimately connected to the physical world than ever before possible. It remains an essential skill in the high-performance,low-level toolkit of the modern embedded systems engineer.