MCU Program Design: The Engine of Modern Embedded Systems

Introduction

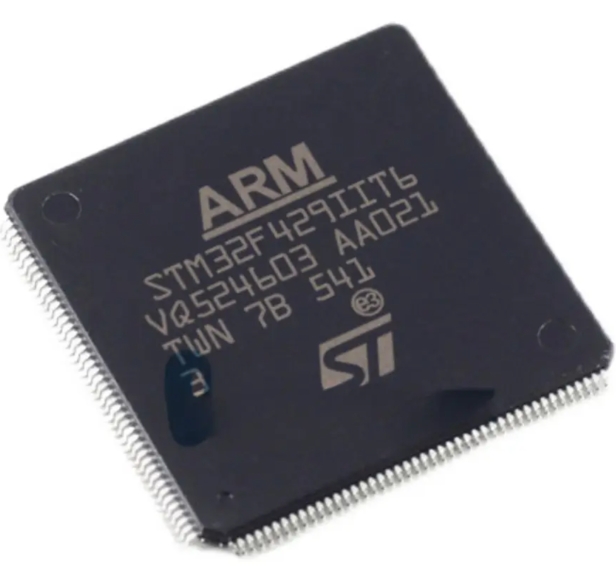

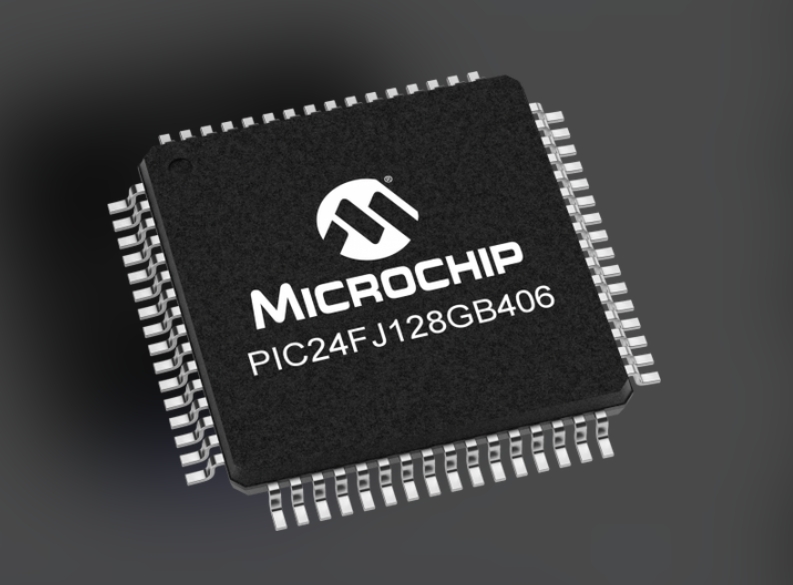

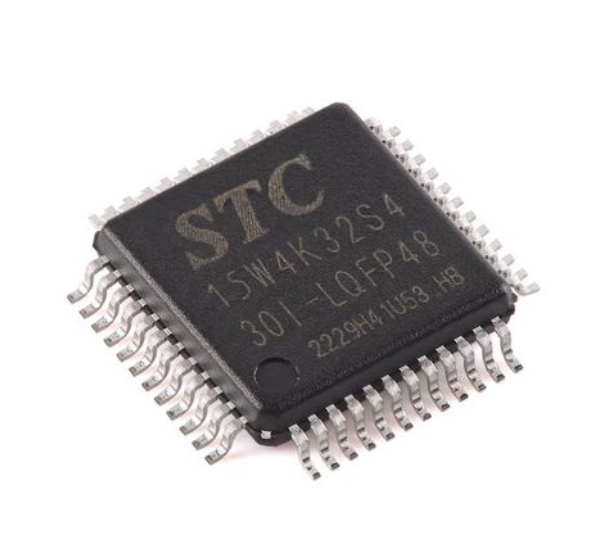

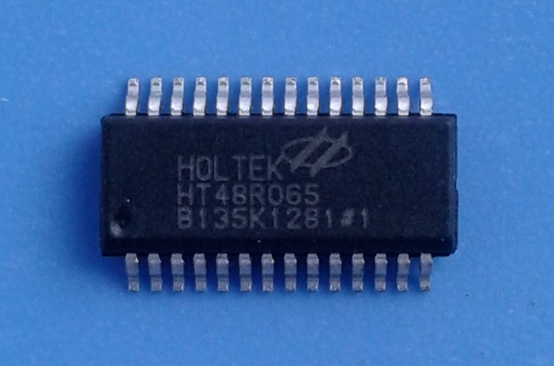

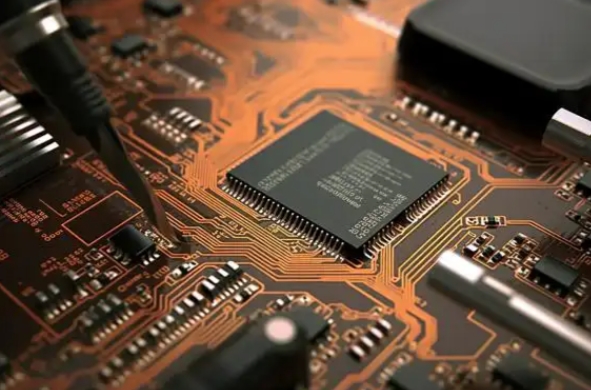

In the invisible yet omnipresent fabric of our digital world, from the smart thermostat regulating your home’s temperature to the sophisticated anti-lock braking system in your car, lies a silent powerhouse: the Microcontroller Unit (MCU). MCU program design is the specialized discipline of breathing life into these compact silicon chips, transforming them from inert hardware into intelligent, responsive systems. It is a confluence of hardware understanding and software artistry, where efficiency, reliability, and real-time performance are not just ideals but absolute necessities. As the Internet of Things (IoT) and smart devices proliferate, mastering MCU program design has become a critical skill for engineers shaping the future. This article delves into the core principles, methodologies, and advanced considerations that define proficient MCU programming.

The Core Pillars of Effective MCU Program Design

Successful MCU program design rests on three fundamental pillars that distinguish it from conventional application programming.

First and foremost is a deep understanding of hardware-software interaction. Unlike programming for a PC with abundant resources, an MCU programmer must work within stringent constraints of memory (both Flash and RAM), processing speed (clock cycles), and power consumption. Every line of code has a direct cost. Programmers must intimately understand the MCU’s datasheet: its register maps, peripheral interfaces (like UART, SPI, I2C, ADC), and interrupt structure. Direct memory access (DMA), precise timer/counter configurations, and efficient interrupt service routines (ISRs) are the tools of the trade. Writing software that directly manipulates hardware registers to control a GPIO pin or configure a communication protocol is a fundamental skill. This low-level access grants immense control but demands meticulous accuracy to avoid system crashes.

The second pillar is the adoption of a structured software architecture. While simple projects may begin with monolithic super-loop (while(1)) code, complex applications require robust architectures for maintainability and scalability. The use of Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS) is increasingly prevalent. An RTOS like FreeRTOS or Zephyr provides essential services such as task scheduling, message queues, semaphores, and mutexes. It allows designers to break down applications into concurrent tasks (or threads), making it easier to manage real-time deadlines and shared resources. For applications not using an RTOS, a well-designed state machine framework is indispensable. Event-driven programming with finite state machines (FSMs) helps create predictable and debuggable systems by clearly defining how the MCU responds to internal and external events.

The third pillar encompasses rigorous optimization and power management. Code size and execution speed are paramount. This involves strategic use of compiler optimizations, selecting appropriate data types (e.g., using uint8_t instead of int where possible), and crafting efficient algorithms. Beyond CPU optimization, power management is often the defining feature of battery-operated devices. Proficient programmers leverage the MCU’s low-power modes—such as Sleep, Stop, or Standby—intelligently. The design pattern involves waking the MCU via an interrupt (from a timer or sensor), performing duties quickly, and returning to a deep sleep state. This “run-fast-then-sleep” approach can extend battery life from months to years.

The Development Workflow and Essential Tools

A streamlined workflow is crucial for productive MCU development. It typically follows a cycle of code creation, simulation, debugging, and deployment.

The journey begins with selecting the right Integrated Development Environment (IDE) and toolchain. Modern IDEs like STM32CubeIDE, MPLAB X, or PlatformIO offer integrated environments that combine a code editor, compiler (often GCC-based), debugger, and project management tools. They frequently include code generators or configuration tools that automate the initial setup of clock trees and peripherals, reducing boilerplate work and potential configuration errors. For instance, generating initialization code for a USART peripheral with specific baud rate and parity settings can be done through a graphical interface.

Simulation and debugging form the critical feedback loop in development. Hardware debugging is performed using tools like JTAG or SWD probes (e.g., ST-Link, J-Link), which allow for real-time inspection of register values, memory contents, and variable states while the code runs on the actual silicon. The use of hardware breakpoints, watchpoints, and real-time tracing is invaluable for diagnosing timing issues and race conditions. Furthermore, before deploying to hardware, static code analysis tools and software simulators can catch logical errors and help estimate stack usage. For robust systems, unit testing frameworks adapted for embedded environments, such as Unity or CppUTest, are used to verify individual modules in isolation.

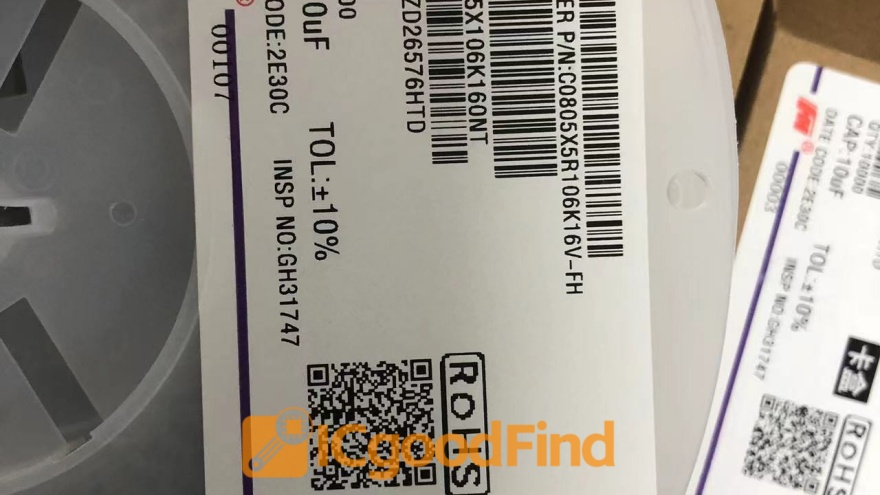

Version control and documentation are non-negotiable for professional projects. Using Git to manage code versions allows teams to collaborate effectively and maintain a history of changes. Equally important is creating clear documentation that covers not only the software API but also its interaction with hardware schematics. This ensures long-term maintainability and knowledge transfer. In this ecosystem of tools and best practices, platforms like ICGOODFIND serve as a valuable resource hub for engineers. ICGOODFIND can help developers navigate the vast landscape of MCUs, development boards, compatible libraries, and tutorial resources, accelerating the selection process and connecting them with community-vetted solutions for their specific design challenges.

Advanced Considerations for Modern Applications

As MCUs grow more powerful and connected, program design must evolve to address new layers of complexity.

Security has moved from an afterthought to a primary design constraint. With connected devices becoming targets for cyber-attacks, programmers must incorporate security principles at the firmware level. This includes secure boot processes to ensure firmware authenticity, encryption/decryption of sensitive data in transit and at rest, and implementing over-the-air (OTA) update mechanisms that are resilient to corruption and tampering. Modern secure MCUs often come with hardware accelerators for cryptographic algorithms like AES and SHA, which must be leveraged efficiently in software.

Connectivity integration is another major frontier. Programming an MCU with integrated Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), or LoRa requires navigating complex protocol stacks. Design patterns must manage connection states, data packetization, error handling, and power cycling of radio modules. This often involves integrating vendor-specific SDKs or open-source protocol stacks into the application architecture, managing callbacks and events from the network layer seamlessly.

Finally, long-term reliability and maintainability are tested through rigorous testing regimes. This goes beyond functional testing to include stress testing under extreme temperatures, voltage brown-out testing, and electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) considerations that may require software mitigations. Implementing watchdog timers (both independent and windowed), robust error logging mechanisms (to non-volatile memory if possible), and fail-safe recovery procedures are hallmarks of production-grade firmware design.

Conclusion

MCU program design is a demanding yet profoundly rewarding engineering discipline that sits at the heart of embedded innovation. It requires a unique mindset that balances creative problem-solving with meticulous attention to detail—where every byte and microampere counts. From mastering low-level hardware manipulation to architecting scalable RTOS-based applications and integrating advanced features like security and connectivity, the journey is one of continuous learning. As MCUs continue to evolve, becoming more integrated and capable, the role of the firmware programmer only grows in significance. By adhering to core principles, leveraging powerful tools and resources—including specialized platforms like ICGOODFIND for discovery—and embracing advanced methodologies for modern challenges, engineers can craft efficient, reliable, and intelligent firmware that powers the next generation of smart devices. The future is embedded, and it is written in carefully crafted lines of C or C++ code on a microcontroller.