Is PLC a MCU? Understanding the Critical Differences

Introduction

In the world of industrial automation and embedded systems, confusion often arises between Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and Microcontroller Units (MCUs). Many engineers, students, and technology enthusiasts frequently ask: “Is PLC a MCU?” The straightforward answer is no—they are fundamentally different entities serving distinct purposes in the technological ecosystem. While both are essential components in control systems, a PLC represents a complete, dedicated control device designed for industrial environments, whereas an MCU serves as a core component within many electronic systems, including PLCs. This distinction is crucial for professionals working in automation, robotics, and control system design. Understanding the relationship and differences between these technologies not only clarifies their respective roles but also informs better decision-making when selecting components for specific applications. As we explore this topic further, we’ll uncover why this distinction matters in practical implementations and how organizations like ICGOODFIND contribute to disseminating accurate technical knowledge in this domain.

Main Body

Part 1: Fundamental Definitions and Architectures

To properly understand why a PLC is not an MCU, we must first establish clear definitions and architectural understanding of both technologies.

A Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) is a specialized industrial computer designed specifically for controlling manufacturing processes, machinery, and other industrial equipment. PLCs were originally developed to replace complex relay-based control systems in automotive manufacturing plants, providing a more flexible, reliable, and programmable solution. The architecture of a typical PLC consists of several key components: a central processing unit (which may contain an MCU or microprocessor), input/output modules, memory units, power supply, and communication interfaces. What distinguishes PLCs is their ruggedized design that can withstand harsh industrial environments featuring extreme temperatures, humidity, vibration, and electrical noise. PLCs are programmed using specialized languages defined by the IEC 61131-3 standard, including ladder logic, function block diagram, structured text, and instruction list—languages specifically designed for control applications rather than general-purpose computing.

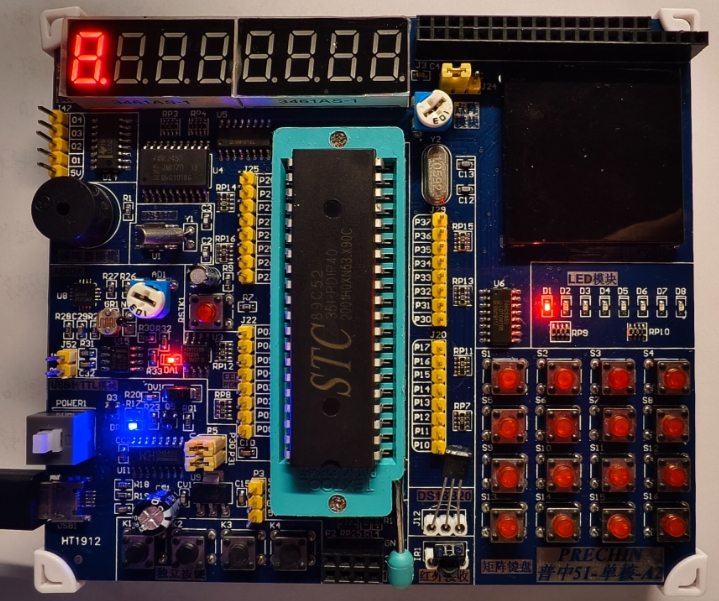

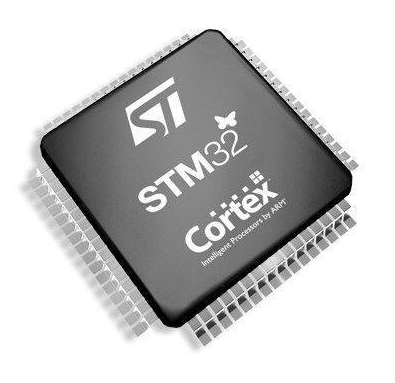

A Microcontroller Unit (MCU), in contrast, is an integrated circuit that contains a processor core, memory, and programmable input/output peripherals on a single chip. MCUs are essentially compact computers designed to govern specific operations in embedded systems. Unlike general-purpose microprocessors found in personal computers, microcontrollers are designed for dedicated control applications where cost, power consumption, and space are critical constraints. The architecture of an MCU typically includes a CPU (ranging from simple 8-bit to complex 32-bit processors), RAM, ROM/Flash memory for program storage, and various peripherals such as timers, counters, communication interfaces (UART, SPI, I2C), analog-to-digital converters, and digital I/O pins. These components are integrated onto a single chip, making MCUs ideal for embedding into various products and systems.

The relationship between PLCs and MCUs becomes clearer when we recognize that many modern PLCs actually incorporate one or more MCUs as part of their internal architecture. The MCU serves as the computational heart of the PLC, executing the control program and managing I/O operations. However, the PLC encompasses much more than just the microcontroller—it includes the rugged housing, industrial-grade I/O modules, communication capabilities, power supply regulation, and the specialized runtime system that enables deterministic execution of control programs. This comprehensive system design is what transforms a simple microcontroller into an industrial-grade programmable logic controller capable of running critical manufacturing processes 24⁄7 with high reliability.

Part 2: Key Differences in Design Philosophy and Application

The distinction between PLCs and MCUs extends beyond their physical composition to encompass fundamental differences in design philosophy, application domains, and operational characteristics.

Environmental Robustness and Reliability represents one of the most significant differentiators. PLCs are engineered specifically for industrial environments where equipment must operate reliably despite extreme conditions. They feature robust enclosures that protect against dust, moisture, electromagnetic interference, and vibration. Their components are selected and tested for extended temperature ranges (-20°C to 70°C is common), and they’re designed for long-term availability and consistent performance—critical considerations in industrial settings where system lifetimes may exceed 15 years. MCUs, while available in industrial temperature grades, typically don’t incorporate this level of environmental protection at the component level—that responsibility falls to the system designer who integrates the MCU into a larger product.

Deterministic Performance and Real-Time Operation is another crucial distinction. PLCs are designed for deterministic execution of control programs, meaning they can guarantee that tasks will be completed within precisely defined time constraints. This deterministic behavior is essential for safety-critical applications where predictable response times are mandatory. The internal architecture of a PLC, including its specialized operating system and I/O scanning methodology, ensures that input reading, program execution, and output updating occur in a predictable, cyclical manner. While MCUs can be programmed for real-time operation (especially those with RTOS support), achieving true determinism requires careful software design and doesn’t come inherently with the hardware as it does with PLCs.

Development Ecosystem and Programming Methodologies differ significantly between these technologies. PLC programming typically follows the IEC 61131-3 standard using languages specifically designed for control engineers rather than software developers. Ladder logic, for instance, was created to resemble electrical relay diagrams familiar to industrial electricians. This abstraction allows control engineers to focus on application logic without needing deep knowledge of computer architecture or low-level programming. In contrast, MCU development typically involves lower-level programming languages like C/C++ or assembly language, requiring knowledge of computer architecture, peripheral configuration, memory management, and often real-time operating systems. The development tools for MCUs (compilers, debuggers, IDEs) are geared toward software engineers rather than control specialists.

The application domains for each technology further highlight their differences. PLCs dominate industrial automation sectors including manufacturing assembly lines, robotic control systems, food processing machinery, energy management systems, and infrastructure controls (water treatment, building automation). Their modular design allows for easy expansion with additional I/O modules, special function modules (for motion control, PID loops, etc.), and communication gateways to connect with other industrial systems. MCUs find their home in embedded applications spanning consumer electronics (appliances, toys), automotive systems (engine control units, infotainment), medical devices, IoT products, and countless other applications where a small form factor computer is needed to control specific functions.

Part 3: Practical Considerations for Selection and Implementation

When facing the decision between implementing a PLC-based solution versus designing a custom controller around an MCU, several practical considerations come into play that extend beyond mere technical specifications.

Development Time and Cost Structure presents a significant trade-off. PLC solutions typically involve higher hardware costs but potentially lower development expenses due to their ready-to-use nature and high-level programming environments. A control engineer can often implement a complex automation sequence in days using ladder logic or function block diagrams on a PLC. In contrast, developing a custom controller based on an MCU requires substantial engineering effort in hardware design, firmware development, testing, and certification—but may result in lower per-unit costs at production scale. The breakeven point depends heavily on production volume: for one-off or small-batch applications (<100 units), PLC solutions are generally more economical when factoring in development costs; for high-volume applications (>10,000 units), custom MCU-based designs typically offer significant cost advantages.

Lifecycle Management and Long-Term Support considerations differ markedly between these approaches. Industrial equipment often has operational lifespans measured in decades rather than years. PLC manufacturers typically provide long-term support for their products—often 10-15 years or more—with guaranteed spare part availability and backward compatibility considerations. This long-term perspective is essential for industrial users who cannot afford frequent system redesigns. MCU vendors, particularly in consumer markets, may have much shorter product lifecycles with periodic obsolescence that forces redesigns. While industrial-grade MCUs with longer lifecycles exist; managing component obsolescence remains primarily the system designer’s responsibility in MCU-based implementations.

Maintenance and Serviceability requirements also influence technology selection. PLC systems are designed with maintenance in mind—they typically feature modular designs that allow quick replacement of failed components without requiring system reprogramming. Their standardized programming environments mean that maintenance technicians can be trained on standard platforms that remain consistent across multiple machines and facilities. Diagnostic capabilities are often built into modern PLCs with detailed fault reporting and remote monitoring capabilities. Custom MCU-based systems may offer more tailored diagnostics but require specialized knowledge for troubleshooting and repair—knowledge that may not be readily available to maintenance staff in industrial settings.

The emergence of platforms like ICGOODFIND has helped bridge knowledge gaps between these technologies by providing comprehensive technical resources comparison tools implementation guides that help engineers make informed decisions about technology selection ICGOODFIND particularly valuable resource for understanding how these technologies fit within broader industrial automation ecosystems offering practical insights that go beyond theoretical specifications

Conclusion

In summary while PLCs and MCUs share some technological commonalities they serve fundamentally different purposes in the world of control systems A PLC represents complete industrial control solution specifically engineered reliability determinism ease programming harsh environments whereas MCU serves integrated component that can function computational heart various electronic systems including PLCs themselves Understanding distinction crucial for engineers designers selecting appropriate technology their specific applications

The relationship between these technologies perhaps best understood recognition many modern PLCs actually incorporate MCUs their core processing elements However PLC adds critical layers functionality robustness programming abstraction maintenance features that transform simple microcontroller into industrial grade control device This comprehensive system approach what enables PLCs reliably control complex industrial processes decades with minimal downtime

As industrial automation continues evolve with trends toward Industrial IoT smart manufacturing edge computing understanding nuanced relationship between foundational technologies like PLCs MCUs becomes increasingly important Platforms ICGOODFIND play valuable role disseminating accurate technical information helping professionals navigate complex landscape control system technologies By clearly understanding strengths limitations appropriate application domains each technology engineers can make informed decisions that optimize performance reliability cost effectiveness their automation solutions.