Basic MCU Knowledge: Your Essential Guide to Microcontroller Fundamentals

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of technology, from smart home devices to advanced industrial automation, a silent yet powerful workhorse operates at the heart of countless innovations: the Microcontroller Unit (MCU). For engineers, hobbyists, and tech enthusiasts, understanding Basic MCU Knowledge is no longer a niche skill but a fundamental literacy in the digital age. This foundational knowledge unlocks the ability to create, customize, and troubleshoot the intelligent electronic systems that permeate our world. Whether you’re taking your first steps into embedded systems or seeking to solidify your core understanding, this guide serves as a comprehensive roadmap. We will demystify the core concepts, architecture, and practical applications of microcontrollers, providing you with the essential toolkit to navigate this critical field. For those looking to deepen their expertise with specialized components and advanced resources, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer invaluable access to component data, application notes, and sourcing information, bridging the gap between theory and real-world implementation.

Part 1: Understanding the Core - What is an MCU?

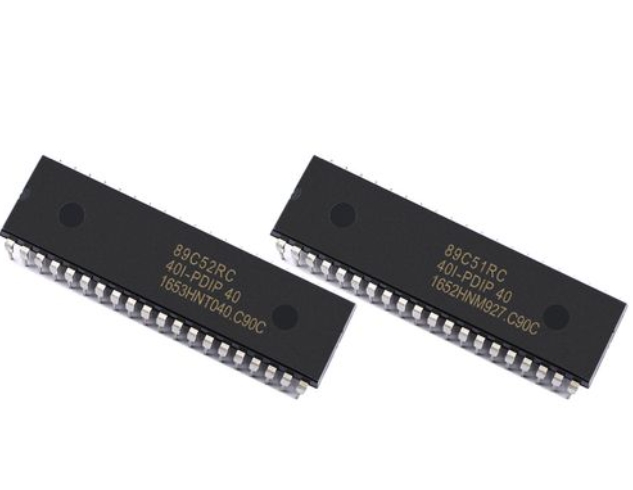

At its simplest, a Microcontroller Unit (MCU) is a compact, self-contained computer system on a single integrated circuit (IC). It is designed to execute specific tasks within an embedded system. Unlike a general-purpose microprocessor (like the CPU in your laptop) that requires external chips for memory and peripherals, an MCU integrates all core components onto one chip. This “all-in-one” design includes a processor core, memory (both volatile and non-volatile), and programmable input/output peripherals.

The key distinction lies in its application. A microprocessor is designed for broad computing tasks where performance and expandability are paramount. An MCU, however, is engineered for dedicated control tasks, emphasizing reliability, low power consumption, cost-effectiveness, and real-time operation. Think of it this way: a microprocessor is the brain of a complex system managing multiple applications, while an MCU is the autonomous nervous system controlling a specific function—like regulating your car’s engine temperature or reading sensor data in a smartwatch.

The basic architecture of an MCU consists of several critical components: * Central Processing Unit (CPU): Executes instructions from the program memory. * Memory: This includes Flash Memory (non-volatile, for storing the program code), SRAM (volatile, for temporary data during operation), and often EEPROM (non-volatile, for storing small amounts of data that must survive power cycles). * Input/Output Ports (I/O): Digital and sometimes analog pins that allow the MCU to interact with the external world—reading switches, sensors (input), and controlling LEDs, motors, or displays (output). * System Bus: The internal communication highway connecting all components. * Clock Generator: Provides the timing pulse that synchronizes all operations. * Peripherals: Integrated specialized circuits like Timers/Counters, Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADC), Serial Communication interfaces (UART, I2C, SPI), and Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM) controllers.

Grasping this integrated architecture is the first pillar of Basic MCU Knowledge. It explains why MCUs are so ubiquitous: their compactness and self-sufficiency make them ideal for embedding into products where space, power, and cost are constrained.

Part 2: The Building Blocks of MCU Operation

Moving beyond static architecture, true understanding comes from knowing how an MCU functions dynamically. This revolves around three core operational concepts: programming, interfacing, and essential peripherals.

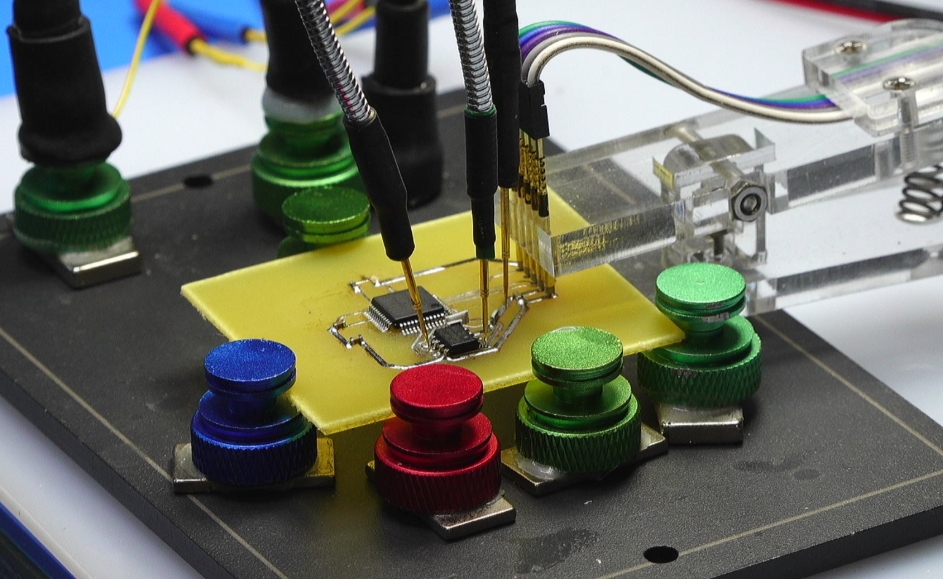

1. Programming and the Development Workflow: An MCU is useless without instructions. Programming involves writing code in languages like C or C++ (occasionally Assembly or higher-level languages) that is compiled into machine-readable hex code. This code is then uploaded or “flashed” onto the MCU’s Flash memory via a programmer/debugger tool. The workflow typically involves: * Writing code in an Integrated Development Environment (IDE). * Compiling and building the code to check for errors. * Flashing the program onto the MCU using a hardware programmer. * Debugging using in-circuit debugging/probing tools. Understanding this flow is crucial. It highlights that software and hardware are intrinsically linked in embedded systems. A simple change in code can alter the physical behavior of a device entirely.

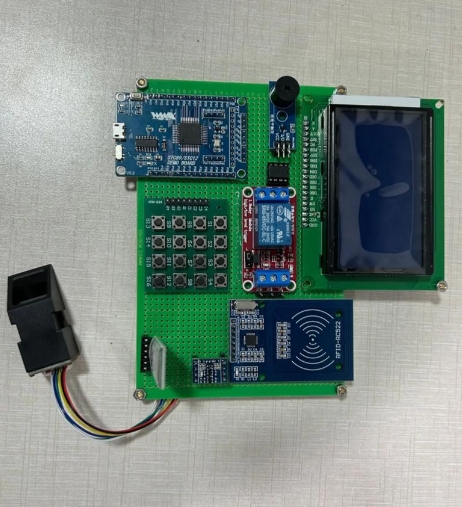

2. Interfacing with the Physical World: The primary job of an MCU is to interact with its environment through its I/O pins. * Digital I/O: Pins can be configured as inputs (to read a high/low voltage from a button) or outputs (to set a pin high/low to turn an LED on/off). This is the most basic form of control. * Analog Interfacing: Many real-world signals (temperature, light intensity) are analog. This is where the Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) peripheral becomes vital. It translates a continuous analog voltage on a pin into a discrete digital number the CPU can process. * Communication Protocols: For talking to other chips or sensors (e.g., a display module or a humidity sensor), MCUs use standard serial protocols: * UART: Simple, asynchronous point-to-point communication. * I2C: A multi-master, multi-slave protocol using only two wires; perfect for connecting multiple low-speed peripherals. * SPI: A high-speed, full-duplex protocol requiring more wires; often used for memory chips or high-data-rate sensors.

3. Utilizing Core Peripherals: Effective use of built-in peripherals separates basic from intermediate knowledge. * Timers/Counters: These are incredibly versatile. They can generate precise time delays without CPU intervention (freeing up CPU resources), measure pulse widths, or create PWM signals. * Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM): By rapidly switching a pin on and off at varying duty cycles, PWM simulates an analog output. It’s the standard method for controlling servo motors, LED brightness (dimming), and motor speed. * Interrupts: Perhaps one of the most important concepts. Instead of the CPU constantly “polling” a pin to check its state (a wasteful process), an interrupt allows an external event (like a button press) to immediately interrupt the main program flow to execute a specific routine. This enables efficient real-time responsiveness, which is critical in control systems.

Mastering these building blocks allows you to move from theoretical understanding to creating functional prototypes that sense, compute, and act—the core cycle of any embedded system.

Part 3: From Theory to Practice - Selecting and Applying an MCU

With foundational knowledge in hand, the next step is applying it. This involves navigating the vast ecosystem of available microcontrollers and initiating practical work.

1. The MCU Ecosystem and Selection Criteria: The market offers MCUs from various vendors like STMicroelectronics (STM32), Microchip (AVR & PIC), Texas Instruments (MSP430), Espressif (ESP32), and many more. Choosing one depends on your project’s requirements: * Processing Power & Architecture: From simple 8-bit cores (e.g., classic AVR) for basic tasks to powerful 32-bit ARM Cortex-M cores for complex algorithms. * Memory Size: Enough Flash for your code and SRAM for data handling. * Peripheral Mix: Does your project need multiple ADCs? Specific communication protocols? Motor control PWMs? * Power Consumption: Critical for battery-powered devices. * Cost & Availability: A major factor in commercial products. * Community & Support: A strong user community and quality documentation can drastically ease development.

This is where comprehensive platforms prove their worth. When researching specifications, comparing part numbers, or seeking reliable sourcing for both common and hard-to-find components during prototyping or production phases, engineers often turn to aggregators like ICGOOODFIND. Such platforms streamline the component selection process by providing centralized technical data and supply chain information.

2. Getting Started with Development Kits: The best way to learn is by doing. Starter kits or development boards (like Arduino Uno based on AVR, STM32 Nucleo boards, or ESP32 dev kits) are ideal for beginners. They break down hardware barriers by: * Providing built-in power regulation and USB programming interfaces. * Breaking out all MCU pins to easy-to-use headers. * Including basic components like LEDs and buttons. * Offering extensive libraries and example codes.

Starting with these kits allows you to focus on software logic and interfacing without first mastering PCB design.

3. Common Application Realms: Your newfound knowledge opens doors to numerous fields: * Internet of Things (IoT): Creating connected devices using Wi-Fi/Bluetooth-enabled MCUs like the ESP32. * Robotics: Controlling motors, reading sensors (ultrasonic, inertial), and implementing logic. * Automation: Building smart home controllers or industrial monitoring systems. * Consumer Electronics: Prototyping new gadgets or customizing existing ones.

Conclusion

Embarking on the journey through Basic MCU Knowledge equips you with more than just technical facts; it provides a new lens through which to view the technological world. You begin to see not just a smart device but an intricate dance of software instructions managing hardware peripherals through a meticulously designed integrated circuit. From understanding the fundamental all-in-one architecture of an MCU to mastering its operational pillars—programming workflow, physical interfacing techniques like ADC conversion and I2C communication, and leveraging critical peripherals such as timers and interrupts—this knowledge forms the bedrock of embedded systems design.

The path forward involves moving from theory to hands-on practice by selecting appropriate hardware through careful evaluation of specs—a process aided by technical resource hubs—and diving into development kits that make experimentation accessible. Ultimately, this foundational literacy empowers you not only as a consumer but as a creator in an increasingly automated world. Whether your goal is professional development or personal project fulfillment, mastering these fundamentals is your first decisive step towards turning innovative ideas into functional electronic reality.