PLC vs. MCU: Understanding the Core Differences and Applications

Introduction

In the realm of industrial automation and embedded systems, two types of controllers reign supreme: the Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) and the Microcontroller Unit (MCU). While both are fundamental components in controlling electronic systems, they serve distinct purposes and operate in different environments. For engineers, designers, and procurement specialists, understanding the difference between a PLC and an MCU is crucial for selecting the right tool for the job. This choice can significantly impact a project’s cost, scalability, reliability, and development timeline. The debate isn’t about which is universally better, but rather which is the optimal solution for a specific application. This article delves deep into the architectures, strengths, weaknesses, and ideal use cases for both PLCs and MCUs, providing a clear framework for decision-making. Whether you are automating a factory assembly line or designing a smart home device, grasping this distinction is the first step toward a successful implementation. Furthermore, platforms like ICGOODFIND can be invaluable resources for sourcing the appropriate components, offering a curated selection of both PLCs and MCUs from various manufacturers to meet diverse project requirements.

Part 1: The Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) - The Industrial Workhorse

A Programmable Logic Controller, or PLC, is a specialized computer designed for industrial environments. Its primary function is to automate electromechanical processes, such as controlling machinery on factory assembly lines, amusement rides, or light fixtures. PLCs were born out of the automotive industry’s need to replace complex relay-based control systems, offering a more flexible, programmable, and reliable solution.

The defining characteristic of a PLC is its ruggedness and reliability. Built to withstand harsh conditions—including extreme temperatures, humidity, vibration, and electrical noise—PLCs are the undisputed champions of the factory floor. They are typically housed in robust enclosures and use industrially-rated components that have a long operational lifespan.

PLCs operate on a cyclic scan cycle, which is fundamental to their deterministic behavior. This cycle consists of three primary steps: reading the status of input devices (e.g., sensors, switches), executing the user-programmed logic (the ladder logic, function block diagram, or structured text), and updating the status of output devices (e.g., actuators, motors, valves). This scan cycle repeats continuously, ensuring that the controller is constantly monitoring and reacting to the state of the system it controls. This predictability is non-negotiable in safety-critical industrial processes where a missed input or delayed output could lead to equipment damage or personal injury.

Programming is typically done using intuitive languages defined by the IEC 61131-3 standard. The most iconic of these is Ladder Logic (LAD), which resembles the electrical relay logic diagrams that electricians and plant engineers were already familiar with. This lowers the barrier to entry for maintenance personnel. Other languages under this standard include Function Block Diagram (FBD), Structured Text (ST), and Instruction List (IL). This standardization simplifies training and allows for some portability of code between different PLC manufacturers, although proprietary elements often remain.

A key advantage of the PLC ecosystem is its modularity. A typical PLC system consists of a central processing unit (CPU) module, power supply module, and various input/output (I/O) modules (digital, analog, specialty). This modular design allows engineers to precisely tailor the system to the application’s needs by simply adding or removing modules. Need to control 100 digital inputs instead of 50? Just add another digital input module. This offers tremendous scalability and ease of maintenance.

In summary, the PLC is a complete, hardened system designed for reliability, determinism, and ease of use in an industrial context. Its strengths lie not just in the processor itself, but in the entire ecosystem built around it—from rugged hardware to standardized programming languages and modular expandability.

Part 2: The Microcontroller Unit (MCU) - The Embedded Brain

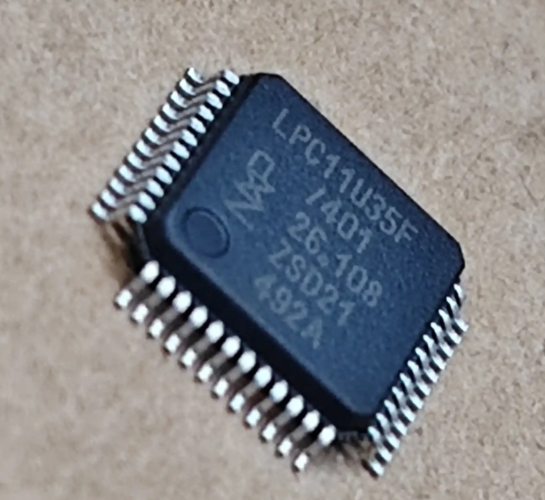

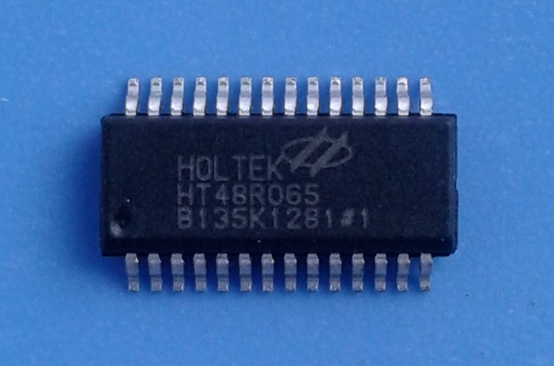

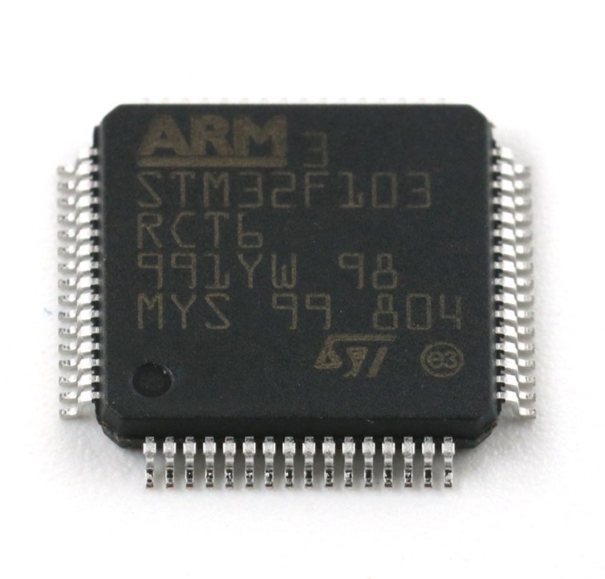

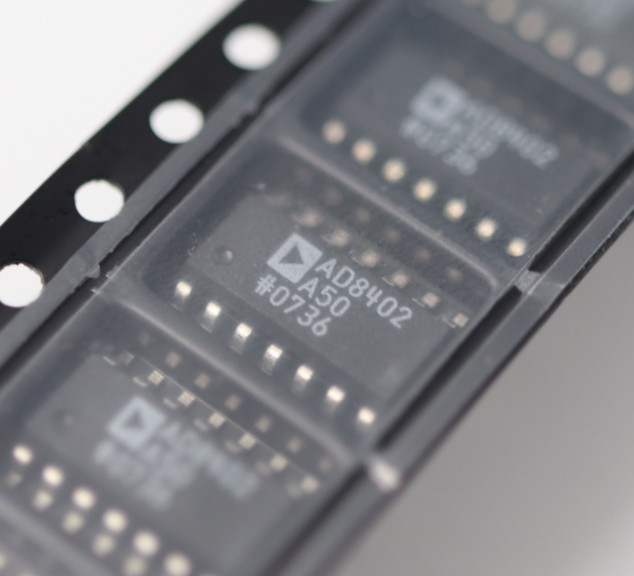

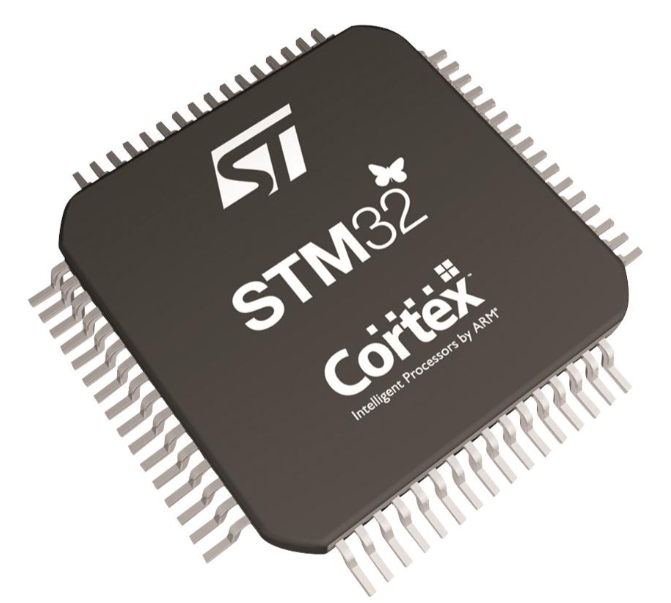

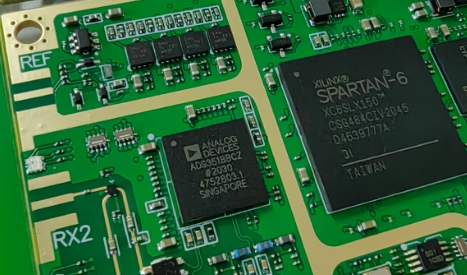

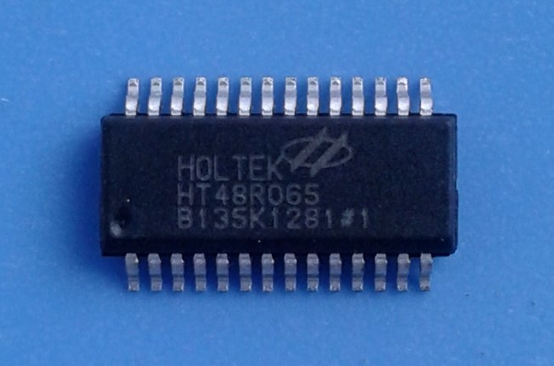

A Microcontroller Unit (MCU) is a compact integrated circuit (IC) designed to govern a specific operation in an embedded system. Often described as a “computer-on-a-chip,” it contains a processor core (CPU), memory (RAM and ROM/Flash), and programmable input/output peripherals all on a single piece of silicon. MCUs are the invisible engines powering countless everyday devices, from your microwave oven and TV remote to advanced medical devices and automotive control units.

The core philosophy of an MCU is integration and cost-effectiveness. By consolidating all the essential computing components into one package, MCUs minimize the physical size, power consumption, and overall cost of the electronic system they control. This makes them ideal for high-volume consumer products where saving every cent and every millimeter of space is critical.

Unlike a PLC’s scan cycle, an MCU’s program execution is typically event-driven. The program flow is often controlled by interrupts. When a specific event occurs—a button is pressed, a timer overflows, or data is received on a communication port—the main program is temporarily halted, and a specific Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) is executed to handle that event. This allows the MCU to remain in a low-power sleep mode when idle and react instantly to critical events, making it highly efficient for applications that do not require constant monitoring.

Programming an MCU involves low-level languages like C or C++. Developers work directly with registers, memory addresses, and hardware peripherals. This offers an unparalleled level of control over the hardware, allowing for highly optimized code that can squeeze out every bit of performance and efficiency. However, this also means development is more complex and time-consuming compared to programming a PLC. It requires deep knowledge of electronics and computer architecture.

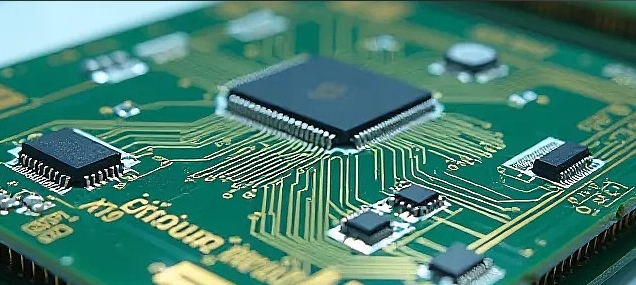

The hardware design process for an MCU-based system is fundamentally different. An engineer must design a custom printed circuit board (PCB) that includes the MCU itself, power regulation circuitry, clock sources (e.g., crystals), and all the necessary connections for inputs, outputs, and communication (USB, UART, I2C, SPI). This offers ultimate design flexibility but also introduces complexity in terms of schematic capture, PCB layout, signal integrity, and manufacturing.

While individual MCUs are not inherently ruggedized like PLCs,they can be deployed in harsh environments as part of a well-designed system. The PCB can be conformally coated, placed in a suitable enclosure,and designed with protection circuits to handle environmental stresses. However,the responsibility for this robustness falls entirely on the system designer,rather than being an inherent feature of the controller itself.

In essence,the MCU is a flexible,cost-effective building block for creating custom embedded solutions.It trades the out-of-the-box robustnessand ease-of-useofaPLCfor greater design freedom,cost savings at scale,and lower power consumption.

Part 3: Head-to-Head Comparison and Choosing the Right Tool

Having explored both devices independently,a direct comparison clarifies their respective niches.The choice between a PLC and an MCU often boils down to a trade-off between development speed/costand unit cost/performance,and between out-of-the-box reliabilityand custom design flexibility.

| Feature | Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) | Microcontroller Unit (MCU) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Industrial Automation,Machine Control | Consumer Electronics,IoT Devices,Auto Electronics |

| Environment | Ruggedized for harsh industrial settings | Requires external design for harsh environments |

| Architecture | Modular,System-on-Module | Highly Integrated,System-on-Chip (SoC) |

| Determinism | High.Deterministic scan cycle. | Event-driven.Can be deterministic with careful programming. |

| Development Speed | Fast.Relatively simple ladder logic programming. | Slower.Complex C/C++ programmingand custom PCB design. |

| Unit Cost | High (\(100 - \)10,000+) | Very Low (\(0.50 - \)20 for the chip) |

| Flexibility | Limited by available modulesand vendor ecosystem | Extreme.Can be tailored to any function. |

| Power Consumption | High(typically line-powered) | Very Low(battery-operated designs possible) |

| Ecosystem | Mature.Vendor-supported hardwareand software. | DIY.Heavily reliant on designer’s expertise. |

When to Choose a PLC:

- For Industrial Applications: Any control task on a factory floor involving heavy machinery,motors,and high-power devicesis squarely in PLC territory.

- When Reliabilityis Paramount: In processes where downtime costs thousands of dollars per minuteor failureis a safety hazard,the proven robustnessof a PLCis worththe investment.

- For Rapid Developmentand Maintenance: If you need to geta machine running quicklyor have plant electricians who can maintain it,ladder logicand modular hardwareare significant advantages.

- For Complex,but Standard,I/O Requirements: When you needto interface with many different typesof sensorsand actuators,a PLC’s modular I/O system simplifies integration.

When to Choose an MCU:

- For High-Volume Products: The low per-unit costof an MCUis decisive in consumer goods.

- When Sizeand Power Matter: For portable,battery-powered devices like wearablesor remote sensors,the small sizeand low power consumptionof an MCUare essential.

- For Highly Customized Functionality: When you needa specific setof peripheralsor unique hardware interactionsthat aren’t served by off-the-shelf PLC modules.

- When You Have In-House Electronics Expertise: If your team has the capabilityto design custom PCBsand write efficient firmware,the MCU offers superior performanceand cost control.

Platforms like ICGOORFIND bridge this world by providing access toboth categories.Fora quick prototypeora small-scale industrial project,a developer might finda compact,P LC-like module built aroundan industrial-grade MCU on ICGOODFIND ,blurringthe lines between these two distinct technologies.

Conclusion

The distinction between PLCs and MCUs is not a matterof superioritybutof specialization.PLCs arethe robust,turn-key solutionsfor industrial automation,p rioritizing reliability,easeof use,and determinism in challenging environments.They abstract away muchof the hardware complexity,allowing engineersand techniciansto focus on application logic.MCUs,in contrast ,arethe versatile,cost-effective coresof embedded systems ,offering unparalleled design freedomand efficiencyatthe expenseof higher development complexityand alackof inherent ruggedness.

The evolutionof technologyis gradually creating some overlap ,with more powerful MCUs entering industrial spacesand compact “soft PL Cs” utilizing MCU-like architectures .However,the fundamental choice remains clear:for controllinga factory,a PLCis your steadfast workhorse;for buildinga million smart home devices ,an MCUis your scalable ,economic al brain .Understanding this core difference empowers engineers tomake informed decisions ,ensuringthatthe right controlleris selectedforthe right job ,leadingto safer ,more efficient ,and more successful technological solutions across all industries .