Difference Between MCU and PLC: A Comprehensive Guide for Engineers

Introduction

In the realm of industrial automation and embedded systems, two pivotal components often stand at the forefront of control applications: the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) and the Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). While both serve as the “brains” of electronic systems, directing operations based on programmed instructions, their design philosophies, application domains, and operational characteristics are markedly different. For engineers, system integrators, and procurement specialists, understanding these differences is not merely academic—it is critical for selecting the right control solution that ensures reliability, cost-effectiveness, and performance. This article delves deep into the architectural, functional, and practical distinctions between MCUs and PLCs, providing a clear framework for decision-making in your next project. For specialized component sourcing that bridges both worlds, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer invaluable access to a global inventory of reliable electronic parts.

Main Body

Part 1: Fundamental Architecture and Design Philosophy

At their core, MCUs and PLCs are built for different environments and expectations, which is reflected in their fundamental architecture.

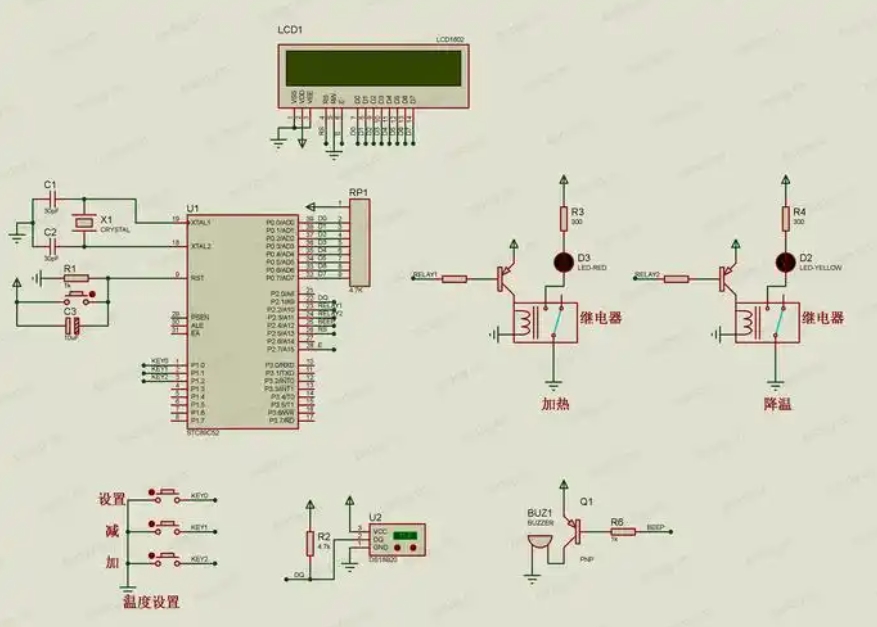

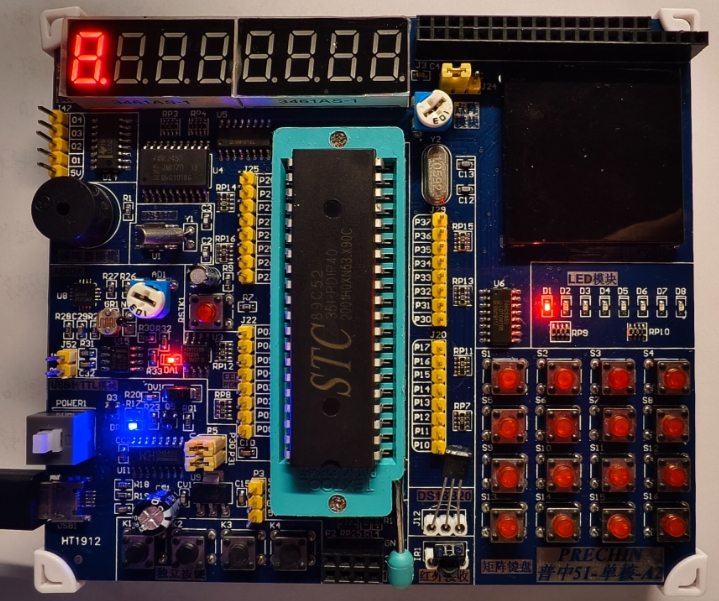

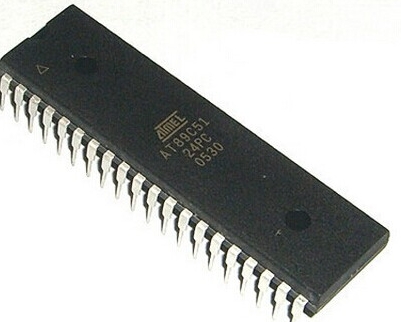

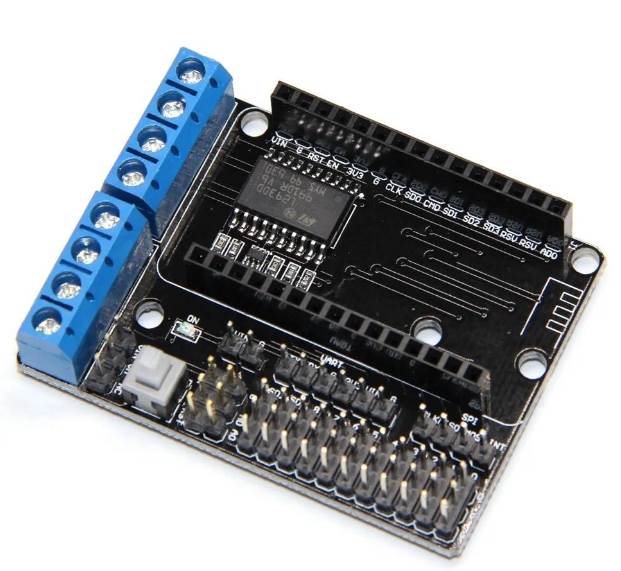

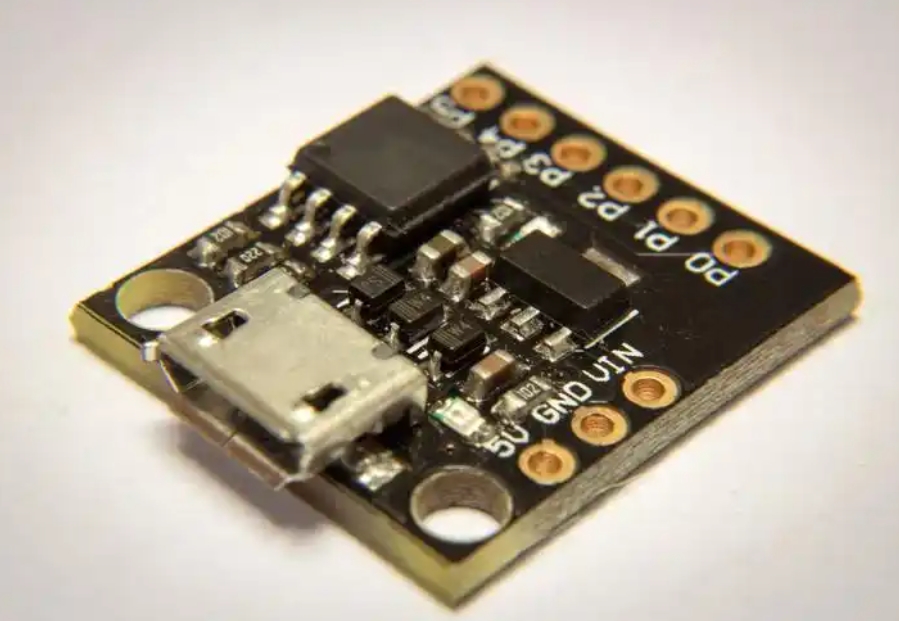

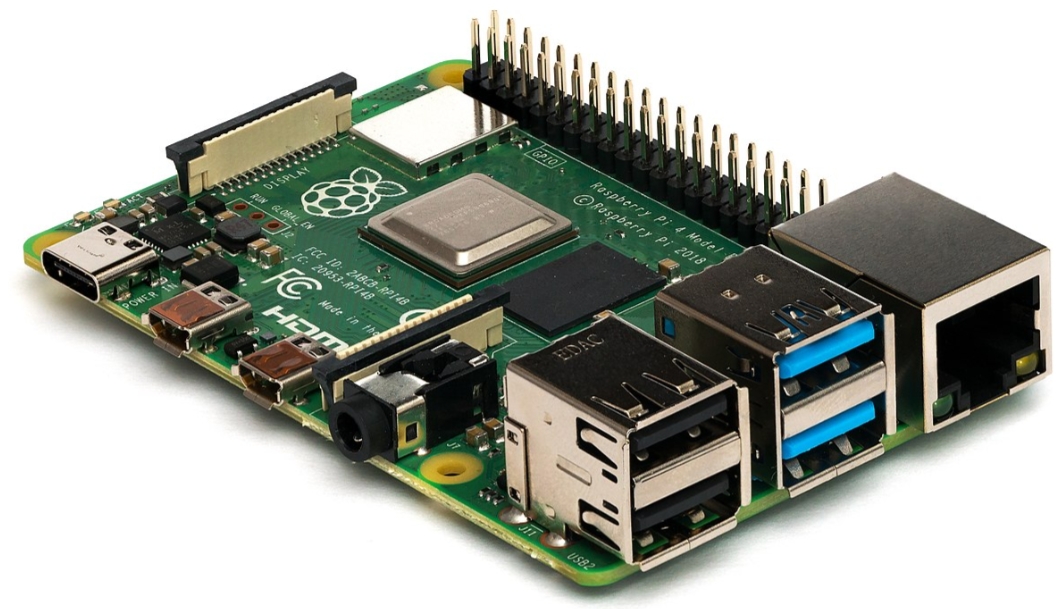

Microcontroller Units (MCUs) are highly integrated semiconductor chips designed as complete computing systems on a single piece of silicon. An MCU typically incorporates a processor core (like ARM, AVR, or PIC), memory (both RAM and Flash/ROM), and programmable input/output peripherals (such as timers, ADCs, and communication interfaces like UART, SPI, I2C). Their design is minimalist and cost-optimized for high-volume embedded applications. MCUs are the quintessential embedded solution, meant to be soldered directly onto a custom-designed printed circuit board (PCB). The development environment is typically low-level, involving programming in C/C++ or assembly, with a strong focus on direct hardware manipulation and resource management.

In stark contrast, a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) is a ruggedized industrial computer system. Its architecture is modular and built around a central processing unit (which may itself contain an MCU or microprocessor). The key differentiator is that a PLC system comprises discrete, interchangeable components: a power supply unit, a CPU module, and various specialized I/O modules (for digital, analog, or communication functions) that slot into a backplane or rack. This modularity is paramount. The design philosophy prioritizes extreme reliability, deterministic operation, and ease of maintenance in harsh industrial environments characterized by electrical noise, vibration, and wide temperature swings. Programming is done at a higher level of abstraction using standardized languages defined by the IEC 61131-3 standard (like Ladder Logic, Function Block Diagram), which are intuitive for electricians and control engineers.

Part 2: Application Domains and Performance Characteristics

The architectural differences directly translate into distinct niches where each technology excels.

MCUs are the engines of dedicated embedded systems. You will find them at the heart of consumer electronics (smart watches, remote controls), automotive subsystems (ECUs, sensors), IoT devices, medical devices, and countless low-cost/high-volume products. Their performance is characterized by flexibility in design but requires significant development effort for each new product. Real-time performance is achievable but must be carefully engineered by the developer in software. The operating environment is generally controlled. The primary advantages here are extremely low unit cost at scale, small form factor, and high design customization.

PLCs are the workhorses of factory automation. They are indispensable in controlling assembly lines, robotic cells, chemical processing plants, packaging machinery, and energy management systems (SCADA). Their performance is defined by deterministic scan cycles, where the PLC reads all inputs, executes the control logic program, and updates all outputs within a guaranteed time frame—a critical feature for synchronized industrial processes. They are built to withstand electromagnetic interference (EMI), run 24⁄7 for years with minimal downtime, and allow for “hot swapping” of I/O modules without shutting down the entire system. The focus is not on raw processing speed but on predictable reliability, ease of troubleshooting with status indicators on every module, and simple integration with industrial networks (Ethernet/IP, Profinet, Modbus). The cost is higher per unit but justified by robustness and reduced engineering time for deployment.

Part 3: Development Cycle, Ecosystem, and Lifecycle Considerations

The journey from concept to deployment diverges significantly between these two technologies.

MCU-based system development is an exercise in hardware-software co-design. It involves: * Schematic & PCB Design: Creating custom circuitry around the chosen MCU. * Firmware Development: Writing efficient code that manages hardware resources directly. * Prototyping & Debugging: Often requiring oscilloscopes and logic analyzers to trace low-level signals. * Certification: If needed for the end market (e.g., FCC, CE). The ecosystem revolves around semiconductor vendors (STMicroelectronics, NXP, Microchip) and their development kits. The lifecycle can be challenging; if an MCU goes end-of-life (EOL), a board redesign may be necessary—a process where sourcing becomes critical. This is where services like ICGOODFIND prove essential for finding authentic components during shortages or for legacy system maintenance.

PLC-based system development follows an integration-centric model: * Hardware Configuration: Selecting appropriate CPU and I/O modules from a vendor’s catalog (e.g., Siemens SIMATIC, Rockwell Automation Allen-Bradley). * Software Programming: Using vendor-specific IDE (like TIA Portal or Studio 5000) with standard industrial languages. * Testing & Simulation: Extensive use of built-in simulation tools before physical commissioning. * Deployment & Documentation: Installing the hardware in an enclosure and documenting the program logic clearly. The ecosystem is dominated by industrial automation vendors who provide long-term support (often 10-15 years), guaranteed spare parts availability, and extensive global technical support networks. The lifecycle management is more straightforward; modules can be replaced like-for-like even years later.

Conclusion

Choosing between an MCU and a PLC is not about which technology is superior but about selecting the right tool for the job. The MCU represents a component-level solution, offering unparalleled customization and cost efficiency for embedded products designed from the ground up. It demands deeper electronics expertise but rewards with optimized performance for specific tasks. Conversely, the PLC represents a system-level solution, delivering bulletproof reliability, modular flexibility, and rapid deployment for industrial control applications. It abstracts hardware complexities away in favor of operational robustness and ease of use for maintenance personnel.

For projects that demand ruggedness in harsh conditions with minimal downtime—think manufacturing or infrastructure—the PLC is invariably the correct choice. For innovative products where size, power consumption, and unit cost are driving factors—think consumer gadgets or specialized sensors—the MCU path is essential. In both scenarios, having a trusted partner for component procurement ensures project continuity. Platforms such as ICGOODFIND serve as a critical bridge in the electronics supply chain, helping engineers navigate part availability whether they are finalizing a custom MCU-based PCB or maintaining a critical PLC-driven production line.