C Language Instruction Set for MCU: The Ultimate Guide for Embedded Developers

Introduction

In the intricate world of embedded systems, the marriage between software and hardware is orchestrated by a fundamental concept: the instruction set. When programming Microcontroller Units (MCUs) in C, developers are not directly writing machine code; instead, they are crafting high-level logic that is meticulously translated into the MCU’s native instructions. Understanding the relationship between the C language constructs and the underlying MCU instruction set is not merely academic—it is a critical skill for writing efficient, reliable, and optimized embedded firmware. This knowledge bridges the gap between abstract programming and physical silicon execution, enabling developers to make informed decisions that impact performance, memory usage, and power consumption. As we delve into this core topic, remember that platforms like ICGOODFIND serve as invaluable resources for engineers seeking specialized components, development tools, and deep technical insights into microcontroller architectures.

Main Body

Part 1: The Abstraction Layer – How C Code Maps to MCU Instructions

C is often termed a “high-level assembly language” for its closeness to hardware, yet it provides a crucial abstraction. The compiler (e.g., GCC, IAR, Keil) acts as the translator. When you write a simple line of C code like int a = b + c;, the compiler’s front-end parses it, and the back-end, tailored to your specific MCU’s architecture (like ARM Cortex-M, AVR, or PIC), generates the corresponding assembly/machine code.

This process involves several key mappings: * Arithmetic/Logical Operations: Basic operators (+, -, &, |, <<) typically translate directly into single CPU instructions like ADD, SUB, AND, OR, and LSL. The compiler selects the most efficient instruction based on context. * Control Flow: if-else statements and loops (for, while) become a series of comparison and conditional branch instructions (e.g., CMP, BEQ, BNE). The compiler optimizes branch prediction and loop unrolling where possible. * Function Calls: A function call involves the instruction set’s calling convention, which governs how arguments are passed (via registers or stack), how the return address is saved, and how the stack frame is managed. Instructions like CALL, BL (Branch with Link), along with stack pointer manipulations (PUSH/POP), are generated. * Memory Access: Accesses to variables, especially global and static ones, involve load and store instructions (e.g., LDR/STR on ARM, LD/ST on AVR). The efficiency depends on the addressing modes offered by the instruction set.

The compiler’s optimization level (-O1, -O2, -Os) profoundly affects this mapping. Higher optimizations might eliminate redundant instructions, inline small functions, or reorder operations, but can sometimes make debugging more challenging.

Part 2: Architecture-Specific Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Different MCU families have distinct instruction sets (RISC vs. CISC, varying register sets), which influence C programming strategies.

-

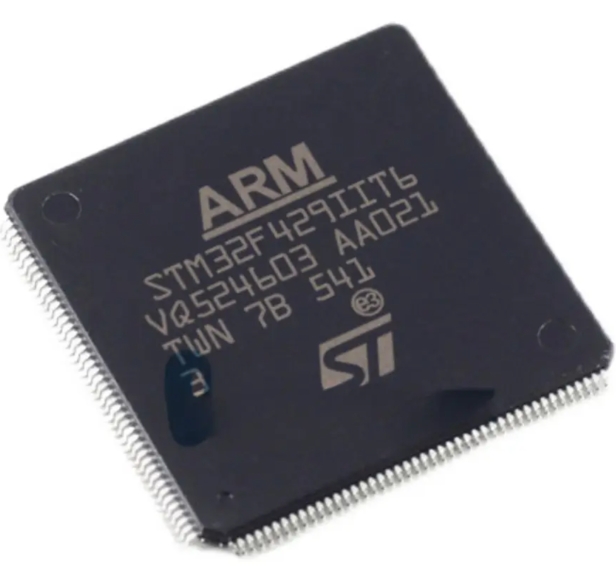

ARM Cortex-M (Thumb/Thumb-2 Instruction Set): A dominant RISC architecture. Its dense 16-bit Thumb instructions improve code density, while Thumb-2 adds 32-bit instructions for better performance. Key implications for C programmers:

- Use of

stdint.htypes (uint8_t,int32_t) is crucial because the native integer size aligns with the processor’s word size (often 32-bit). Misusing plainintcan lead to inefficient code. - Understanding the limited number of general-purpose registers (R0-R12) encourages writing functions with fewer parameters.

- Bit-banding, a feature in some Cortex-M cores, allows atomic bit manipulation through specific memory addresses, which can be accessed via clever pointer arithmetic in C.

- Use of

-

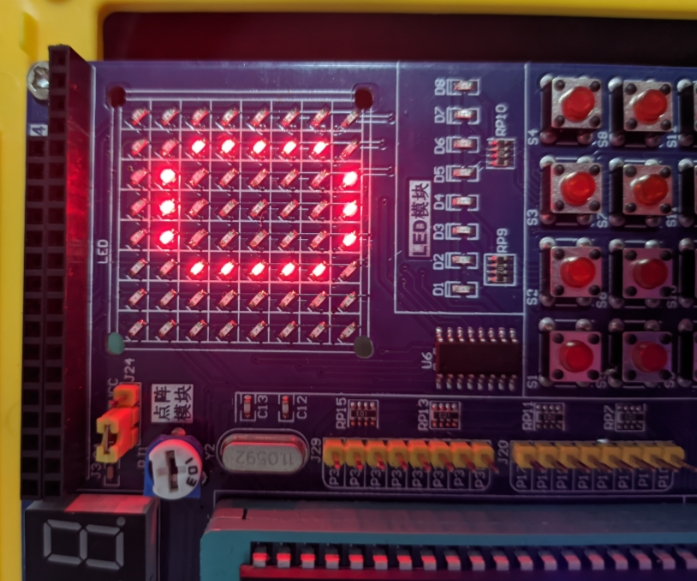

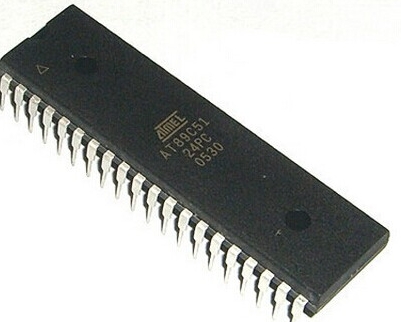

AVR (8-bit RISC): Known for its simplicity. Its instruction set has clear limitations that shape C code:

- Memory space is segregated into Flash, RAM, and EEPROM. Keywords like

PROGMEM(in AVR-GCC) must be used to store constant data in Flash, as RAM is scarce. - Operations on 16-bit or 32-bit integers are synthesized from multiple 8-bit instructions, making them slower. Using the smallest adequate data type is a critical optimization.

- Direct access to I/O registers via special pointers (

PORTB,DDRB) maps directly to specific I/O instructions (IN,OUT,SBI).

- Memory space is segregated into Flash, RAM, and EEPROM. Keywords like

-

Optimization Strategies Rooted in Instruction Set Knowledge:

- Minimize Global Variables: They require absolute addresses in load/store instructions. Favor local variables that can be held in registers.

- Use Appropriate Data Types: Match data types to the ALU’s native width. Avoid

floatordoubleon MCUs without a Floating-Point Unit (FPU); use fixed-point arithmetic instead. - Inline Critical Functions: For tiny, performance-critical functions, use the

inlinekeyword to save the overhead of call/return instructions. - Understand Volatile: The

volatilekeyword tells the compiler that a variable can change outside program flow (e.g., a hardware register). This prevents the compiler from optimizing away necessary read/write instructions.

Part 3: Practical Tools and Debugging at the Instruction Level

Writing optimal C code requires tools that let you peer beneath the abstraction.

- Inspecting Disassembly: The most direct method. Modern IDEs allow you to view the disassembly window while debugging. Here, you can see the exact sequence of MCU instructions generated from your C source line. This is essential for verifying compiler optimizations and identifying unexpected code bloat.

- Linker Map Files: These files show how your code and data are laid out in memory. They help you understand the final footprint of your functions and variables relative to the MCU’s memory map.

- Profiling and Benchmarking: Use on-chip debug probes (like JTAG/SWD) with profiling tools to measure cycle counts for critical routines. This directly reflects instruction set efficiency.

- Intrinsic Functions and Inline Assembly: For utmost control, compilers provide intrinsic functions (e.g.,

__CLZ()for Count Leading Zeros on ARM) that map directly to single, efficient instructions. In rare cases where no C equivalent exists, carefully used inline assembly allows you to embed specific instructions directly in your C code.

Platforms like ICGOODFIND are instrumental in this phase, providing access to a wide range of development boards, specialized debuggers, programmer tools, and detailed MCU documentation that are essential for effective low-level development and analysis.

Conclusion

Mastering the interplay between C language programming and the MCU instruction set transforms an embedded developer from a coder into an architect of efficient systems. It empowers you to write C code that is not just functionally correct but also inherently efficient because you understand its direct consequences on the hardware. From selecting the right data type to strategically using compiler directives and analyzing disassembly, this knowledge is pivotal for overcoming the constraints of limited memory, processing power, and energy in embedded environments. As MCUs continue to evolve with more complex cores and extended instruction sets, continuous learning through datasheets, application notes, and curated hardware platforms remains vital. Resources such as ICGOODFIND facilitate this journey by connecting developers with the precise tools and components needed to implement and optimize their understanding of C and instruction sets in real-world microcontroller applications.