The Making of an 8051 MCU Smart Car: A Journey into Embedded Intelligence

Introduction

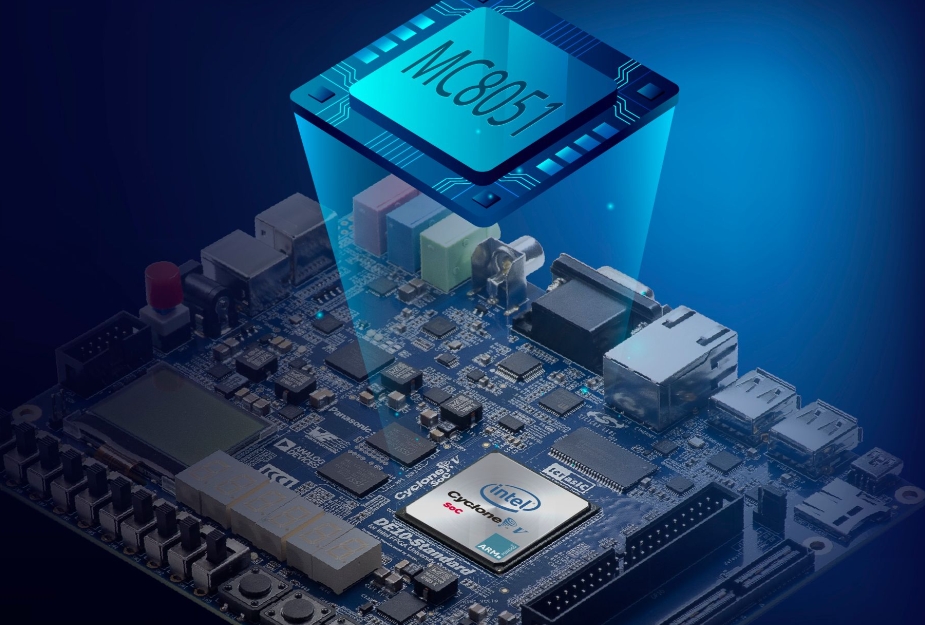

The realm of embedded systems is a fascinating intersection of hardware and software, where simple microcontrollers breathe life into inert electronic components. At the heart of countless educational and industrial projects lies the venerable 8051 microcontroller—a classic, robust, and incredibly versatile chip that has stood the test of time. This article delves into the intricate process of creating a smart car powered by the 8051 MCU, a project that not only demonstrates fundamental engineering principles but also serves as a gateway to the world of autonomous systems. The journey from a collection of discrete parts to a responsive, intelligent vehicle encapsulates the essence of practical electronics. For engineers, students, and hobbyists seeking reliable components and inspiration for such projects, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer an invaluable repository of parts and data sheets, streamlining the development process. This guide will walk you through the core stages of building your own 8051-based smart car, highlighting key design choices, implementation strategies, and the underlying intelligence that makes it “smart.”

Main Body

Part 1: Laying the Foundation - Hardware Design and Component Selection

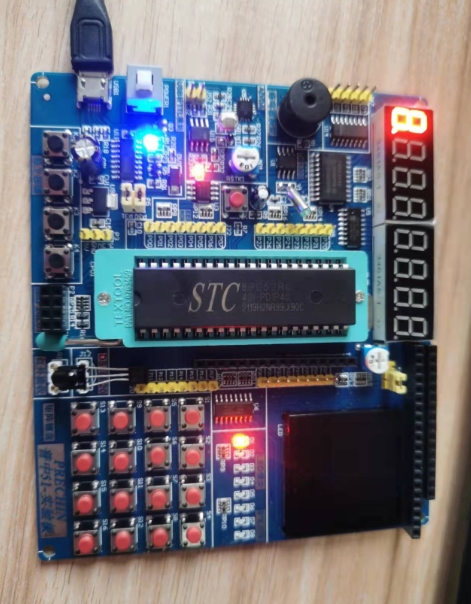

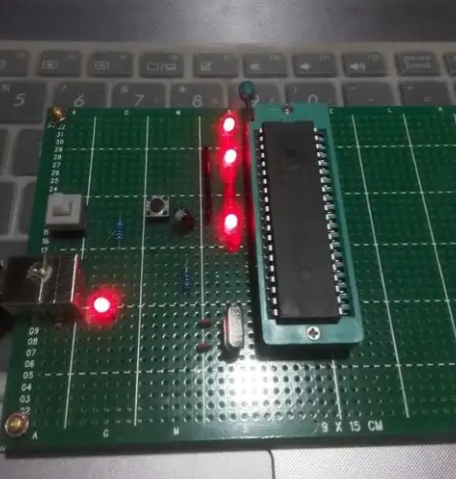

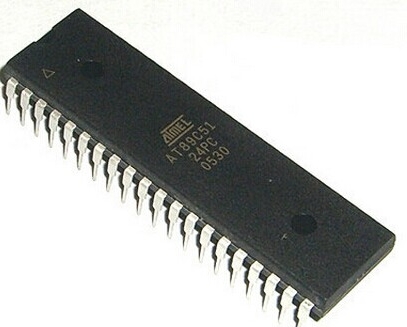

The construction of an 8051 MCU smart car begins with a meticulous hardware design phase. This stage is critical as it defines the car’s capabilities, performance, and overall reliability. The central nervous system of the vehicle is, unsurprisingly, the 8051 Microcontroller Unit (MCU). Chosen for its simplicity, widespread availability, and extensive documentation, the 8051 acts as the brain that processes sensor data and issues commands to the motors. Its architecture, featuring I/O ports, timers/counters, and serial communication capabilities, is perfectly suited for this application.

The chassis forms the physical backbone of the car. It can be a simple acrylic or metal frame designed to house all components securely. The choice of motors is paramount; typically, DC geared motors are used for their good torque and ease of control. These motors are connected to wheels, and their rotation is managed by a critical component known as a motor driver. An L293D or L298N motor driver IC is almost universally employed in such projects. This driver acts as an intermediary between the low-power 8051 MCU and the high-power motors, allowing the MCU’s signals to control the motors’ direction and speed through a technique called Pulse Width Modulation (PWM).

Power management is another cornerstone of the hardware design. A stable and adequate power supply is non-negotiable. The motors, sensors, and MCU often have different voltage requirements (e.g., 12V for motors, 5V for the logic circuits). Therefore, a combination of batteries (like Li-Po or AA cells) and voltage regulators (like the 7805) is used to ensure each component receives the correct voltage. A poorly designed power circuit can lead to erratic behavior or permanent damage to sensitive components.

For the car to be “smart,” it must perceive its environment. This is achieved by integrating a suite of sensors. The most common sensors include: * Infrared (IR) Sensors: Used for line-following applications. They emit IR light and detect its reflection to distinguish between a light surface (e.g., a white track) and a dark line. * Ultrasonic Sensors (e.g., HC-SR04): Used for obstacle avoidance. They emit ultrasonic waves and measure the time taken for the echo to return, calculating the distance to any object in front of the car. * Bluetooth Module (e.g., HC-05): Allows for wireless control and data transmission from a smartphone or computer, adding a layer of remote intelligence.

Sourcing these components can be a project in itself. This is where resources like ICGOODFIND prove indispensable. By providing a centralized platform to find datasheets, compare components, and locate suppliers, ICGOODFIND significantly accelerates the procurement and research phase, ensuring you select the right parts for your specific design goals.

Part 2: The Brain’s Instructions - Software Development and Programming Logic

With the hardware assembled, the next phase involves writing the software that will animate the car. The 8051 MCU is typically programmed in C language or Assembly, with C being the preferred choice due to its balance of efficiency and readability. The code is written on a PC using an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) like Keil µVision or SDCC (Simple DirectMedia Layer), then compiled into a hex file that is burned onto the MCU’s memory using a dedicated programmer.

The software’s primary role is to continuously read inputs from the sensors and decide on appropriate actions for the motors. This creates a continuous sense-plan-act cycle. Let’s consider two fundamental smart behaviors: line following and obstacle avoidance.

For a line-following robot, the logic revolves around data from IR sensors mounted on the underside of the car’s front. A typical setup uses two or three sensors. * Logic: If the left sensor detects the line (black), it means the car is drifting to the right. The program should command the right motor to stop or slow down, causing the car to turn left until both sensors are back on white. * Conversely, if the right sensor detects the line, the left motor is controlled to turn right. * If both sensors are on white, the car moves forward. * If both sensors are on black (a possible intersection or end-of-line), a predefined action like stopping or turning can be executed.

This logic is implemented using simple if-else statements in an infinite loop, constantly checking the status of the sensor pins connected to the 8051’s I/O ports.

For obstacle avoidance, the ultrasonic sensor takes center stage. * Logic: The program triggers the ultrasonic sensor to send a pulse. * It then listens for the echo and calculates the distance based on the time elapsed. * A conditional check is performed: if (distance < safe_threshold) { avoid_obstacle(); }. * The avoid_obtacle() function would typically involve stopping the car, reversing slightly, and then turning left or right for a set duration before resuming forward motion and checking again.

More advanced implementations can incorporate state machines, where the car exists in different states (e.g., FORWARD, TURN_LEFT, STOP), and sensor inputs trigger transitions between these states. This makes the code more organized and scalable. Furthermore, integrating a module like Bluetooth allows part of this decision-making logic to be offloaded to a remote device, enabling features like manual override or more complex AI-driven pathfinding algorithms processed on a smartphone.

Part 3: System Integration, Calibration, and Troubleshooting

The final stage of “the making” is arguably the most challenging: bringing hardware and software together into a cohesive, functional unit. This phase involves system integration, where all subsystems—power, sensing, computation, and actuation—are connected and tested as a whole.

The first step after assembly is calibration. Sensors are rarely perfect out of the box. For instance: * IR Sensor Calibration: The threshold value that distinguishes “black” from “white” can vary with ambient light and surface reflectivity. The code must be adjusted to read analog values (if using ADCs) or fine-tune digital thresholds to ensure reliable detection. * Ultrasonic Sensor Calibration: The calculated distance might need an offset based on empirical testing against a ruler to ensure accuracy. * Motor Calibration: Due to minor physical differences, two identical motors might not run at exactly the same speed when given the same PWM signal. This can cause the car to drift instead of moving in a straight line. The software must incorporate a “trim” or correction factor for one motor to compensate.

Troubleshooting is an inevitable part of this process. Common issues include: * The car does nothing: Check power connections, voltage levels at all key points (MCU Vcc, motor driver enable pins), and ensure the program was correctly burned onto the MCU. * Motors spin but car doesn’t move: Check mechanical coupling between motors and wheels. * Erratic sensor behavior: Check for loose wiring, electrical noise (use decoupling capacitors near ICs), and ensure sensor power requirements are met. * Car behaves illogically: This is almost always a bug in the software logic. Methodically go through the code, add debug statements (if a serial connection is available), or use LEDs on unused I/O pins to indicate program flow.

This iterative process of testing, identifying faults, hypothesizing solutions, and re-testing is where true learning occurs. It transforms theoretical knowledge into practical skill. Throughout this phase of debugging and refining your design, consulting detailed component specifications is crucial. A resource like ICGOODFIND can be your quick reference guide to confirm pinouts, voltage tolerances, and timing diagrams for your specific 8051 variant or sensor module.

Conclusion

The journey of making an 8051 MCU smart car is a profoundly educational endeavor that encapsulates the entire product development lifecycle—from conceptualization and component selection through programming and final integration. It solidifies one’s understanding of microcontroller architecture, real-time sensor data processing, closed-loop control systems, and practical problem-solving. While modern 32-bit ARM-based MCUs offer more power and features, starting with an 8051 provides an unparalleled foundation in core embedded concepts without unnecessary complexity.

This project demonstrates that intelligence in machines often begins with simple decision trees executed reliably at high speed. The satisfaction of seeing a collection of parts autonomously navigate a track or avoid obstacles is immense. As you embark on or refine your own smart car project, remember that platforms like ICGOODFIND exist to support your innovation by simplifying access to critical information about integrated circuits like our central protagonist here—the versatile 8051 microcontroller—and all its supporting cast of components.