MCU Timing Program: The Heartbeat of Embedded Systems

Introduction

In the intricate world of embedded electronics, where microcontrollers (MCUs) orchestrate everything from smart home devices to advanced automotive systems, timing is not just a feature—it is the fundamental heartbeat. An MCU Timing Program governs the precise execution of tasks, manages peripheral interactions, and ensures reliable system behavior. This foundational element separates a functional, responsive device from an erratic and unreliable one. As systems grow more complex, mastering timing programs becomes critical for developers aiming to optimize performance and resource utilization. This article delves into the core principles, implementation strategies, and advanced considerations of MCU timing, highlighting why a structured approach is indispensable for modern embedded design. For engineers seeking to deepen their expertise in this niche, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer curated resources and component insights that can streamline the development process.

The Core Principles of MCU Timing

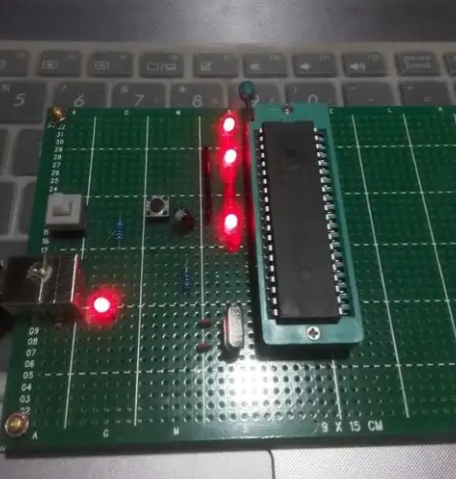

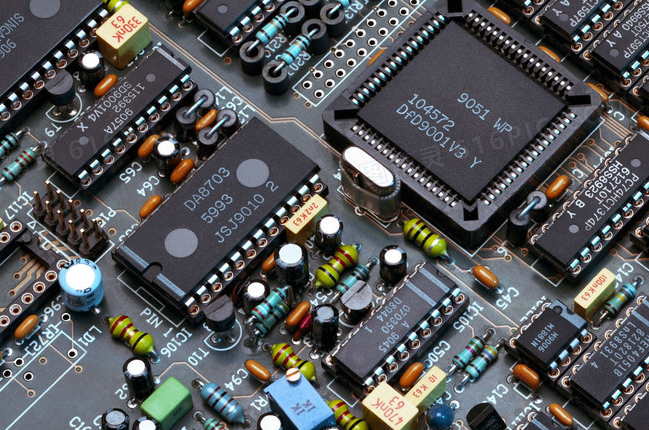

At its essence, an MCU timing program controls when and how specific operations occur within the microcontroller. Unlike general-purpose computers, MCUs often operate in real-time environments where delays or jitter can cause system failure. The cornerstone of timing management lies in the hardware timers/counters integrated into the MCU silicon. These are dedicated circuits that count clock cycles or external events with high precision.

Hardware timers are the most reliable method for generating precise delays and measuring time intervals. They operate independently of the main CPU execution flow, meaning they can run in the background while the processor handles other tasks. Developers configure these timers by setting pre-scalers (to divide the master clock frequency) and compare/match registers to define specific timeouts or pulse widths. This hardware-centric approach is far superior to simple software delay loops, which are highly inaccurate and block the CPU from performing any other work.

Another fundamental concept is interrupt-driven timing. Here, a timer is configured to generate an interrupt request (IRQ) upon reaching a specific count. The CPU momentarily pauses its current task, executes a dedicated Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) to handle the timed event (e.g., toggling a pin, reading a sensor), and then returns to its previous operation. This model is efficient for periodic tasks and forms the basis for Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS). Understanding the interplay between timer configuration, interrupt priorities, and ISR efficiency is crucial. A poorly designed ISR that takes too long to execute can cripple system responsiveness.

Furthermore, clock source integrity is paramount. The accuracy of any timing program is directly tied to the stability of the MCU’s clock source, whether it’s an internal RC oscillator or an external crystal. For applications requiring high temporal precision, such as digital communication protocols (UART, I2C, SPI) or motor control PWM signals, selecting and calibrating the appropriate clock source is a critical first step in the design phase.

Implementing Robust Timing Architectures

Moving from theory to practice requires a structured methodology. The first step is requirements analysis: determining all timing constraints of the system. This includes periodic tasks (e.g., sensor sampling every 10ms), one-shot delays, timeout monitoring for communication, and generating precise output signals like PWM for motor speed control. Documenting these requirements helps in selecting the right MCU with a sufficient number and type of timer peripherals.

The implementation phase often involves leveraging timer operational modes. Most modern MCUs offer timers with multiple modes: * Output Compare Mode: Used to generate precise waveforms or trigger events when the timer count matches a set value. * Input Capture Mode: Used to precisely measure the duration or frequency of an external signal. * PWM Generation Mode: A specialized output compare mode for creating pulse-width modulated signals essential for controlling power delivery to LEDs, motors, and servos. * Counter Mode: Where the timer counts external pulses rather than internal clock cycles.

For complex systems managing multiple concurrent timing tasks, moving beyond bare-metal interrupt management to a Real-Time Operating System (RTOS) is highly beneficial. An RTOS provides abstractions like software timers, tasks (threads), and scheduling policies (e.g., preemptive priority-based scheduling). It allows developers to manage complex timing relationships more maintainably by defining tasks that run at specific frequencies without worrying about low-level hardware register manipulation. However, it introduces overhead and requires understanding of concepts like task synchronization and resource management.

A critical best practice is avoiding blocking code in the main loop or critical ISRs. Long-running operations must be broken into state machines or delegated to low-priority tasks. Additionally, using watchdog timers as a safety mechanism is essential. A watchdog timer is a separate timer that must be periodically reset by the software; if it isn’t (due to a software crash or infinite loop), it triggers a system reset. This ensures reliability in deployed systems.

Advanced Considerations and Optimization

As projects scale, advanced timing considerations come to the fore. Power consumption is directly linked to timing management. Many MCUs offer low-power sleep modes where the core CPU halts but specific timers remain active. A timing program can be designed to place the MCU into deep sleep and use a low-power timer to wake it up at precise intervals for data processing—a technique vital for battery-powered IoT devices.

Timer synchronization in MCUs with multiple timer units allows for coordinated actions across different peripherals. For example, in advanced motor control or digital power conversion, multiple PWM outputs may need perfectly aligned edges or defined dead times, which can be managed by synchronizing timers.

Another advanced topic is dealing with timer overflow and resolution. Developers must plan for what happens when a 16-bit or 32-bit timer reaches its maximum value and rolls over to zero. Calculations for time intervals must account for this overflow to avoid errors. Similarly, understanding timing resolution—the smallest time change detectable or generable—is key. It is determined by the clock frequency and pre-scaler settings; higher clock speeds yield finer resolution but may increase power consumption.

Finally, debugging and profiling timing behavior are specialized skills. Using oscilloscopes or logic analyzers to probe GPIO “debug pins” toggled within ISRs is a common method to visualize timing and measure execution time. Some modern IDEs and toolchains also offer trace functionality that can profile code execution non-intrusively.

For engineers navigating these complexities—from selecting an MCU with adequate timer peripherals to debugging subtle race conditions—leveraging expert resources can save immense time. Platforms dedicated to component discovery and technical deep dives, such as ICGOODFIND, provide valuable insights into compatible hardware and proven design patterns that fulfill stringent timing requirements.

Conclusion

Crafting an effective MCU Timing Program is a multidimensional challenge that sits at the intersection of hardware understanding and software discipline. From configuring low-level hardware registers for nanosecond precision to architecting high-level RTOS-based task schedulers, timing permeates every layer of embedded system design. A robust timing strategy ensures reliability, efficiency, and determinism—qualities non-negotiable in today’s connected world of intelligent devices.

The journey involves mastering fundamental principles like hardware timers and interrupts, adopting structured implementation architectures, and eventually tackling advanced optimization for power and performance. As applications demand more from smaller footprints, continuous learning becomes essential. Engaging with specialized engineering communities and resource platforms like ICGOODFIND can accelerate development by providing access to critical information on components and methodologies tailored for real-time embedded challenges.

Ultimately, proficiency in MCU timing is not merely about making things happen; it’s about making them happen at exactly the right moment, every time—a skill that defines excellence in embedded systems engineering.