C Language Program Design and Application for MCU

Introduction

In the realm of embedded systems, the microcontroller unit (MCU) stands as the fundamental building block, powering everything from household appliances to advanced industrial automation. At the heart of programming these versatile chips lies the C programming language. Its efficiency, control over hardware, and portability have made it the de facto standard for MCU development for decades. This article delves into the core principles of C language program design specifically for microcontroller applications, exploring its critical advantages, practical implementation strategies, and real-world use cases. Mastering C for MCUs is not merely about learning syntax; it’s about understanding how to bridge high-level logic with low-level hardware control to create efficient and reliable embedded solutions.

Main Body

Part 1: The Unrivaled Synergy Between C and MCU Architecture

The enduring partnership between C and microcontrollers is no accident. It is rooted in the language’s inherent characteristics that align perfectly with the constraints and requirements of embedded systems.

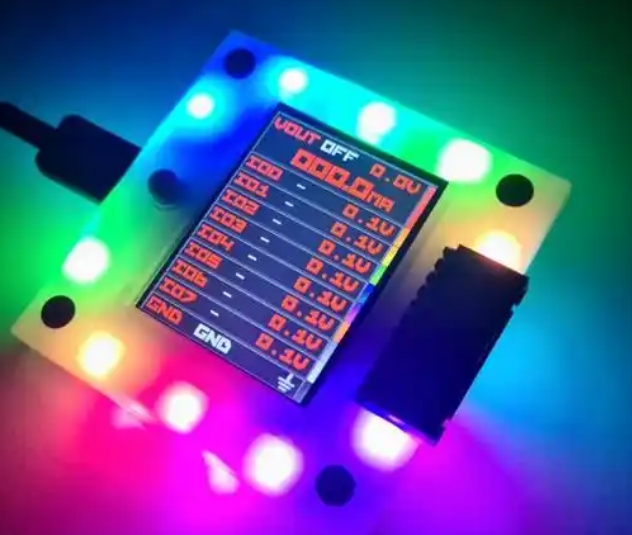

First and foremost, C provides an exceptional balance between high-level abstraction and low-level hardware access. Unlike higher-level languages like Python or Java, C allows developers to manipulate memory addresses, registers, and I/O ports directly through pointers and specific memory-mapped I/O. This is crucial for MCUs, where controlling peripherals like GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output), ADCs (Analog-to-Digital Converters), timers, and communication interfaces (UART, SPI, I2C) is a daily task. Functions can be written to read from or write to specific memory locations that correspond to hardware registers, giving the programmer precise control over the MCU’s behavior.

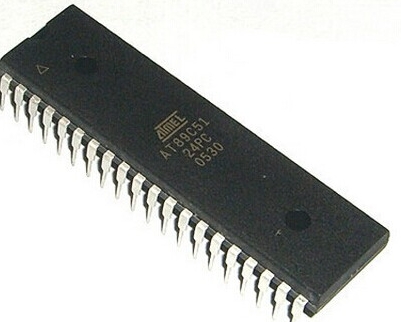

Secondly, C generates highly efficient and compact machine code. MCUs often operate with limited resources—constrained RAM, Flash memory, and processing power. C compilers (like GCC for AVR, ARM-GCC, or proprietary tools from Keil or IAR) are highly optimized to produce lean executable code that minimizes memory footprint and maximizes execution speed. The language’s simplicity and lack of overhead from features like garbage collection or extensive runtime libraries make it ideal for resource-constrained environments.

Furthermore, the portability of C code across different MCU platforms is a significant advantage. While hardware register definitions change between MCU families (e.g., an ARM Cortex-M4 vs. a legacy 8051), the core logic of algorithms, data structures, and control flow written in C can often be reused. The bulk of the code can be made portable by isolating hardware-dependent sections into well-defined driver modules. This reduces development time when migrating projects to newer or more powerful microcontroller families.

Part 2: Core Design Principles and Practical Application Patterns

Designing robust C programs for MCUs requires adherence to specific principles that ensure reliability, maintainability, and efficiency.

Structured Modular Programming is paramount. Code should be organized into modular .c source files and corresponding .h header files. Each module should have a single, well-defined responsibility—for example, a module for handling UART communications, another for driving an LCD display, and another for implementing a sensor data processing algorithm. This separation eases debugging, testing, and team collaboration. Header files act as contracts, declaring public functions, macros, and data types without exposing implementation details.

Direct Memory and Peripheral Management is a cornerstone skill. Programmers must understand the MCU’s memory map and datasheet. Accessing a peripheral typically involves: 1. Configuring control registers (e.g., setting baud rate for a UART). 2. Enabling interrupts if needed (by setting interrupt enable bits). 3. Writing data to output registers or reading from input registers. For instance, toggling an LED connected to a GPIO pin might involve using a bitwise OR operation to set a bit in a port output register: PORTB |= (1 << LED_PIN);. Mastery of bitwise operators (&, |, ^, ~, <<, >>) is non-negotiable for efficient hardware control.

Interrupt-Driven Architecture vs. Polling is a critical design choice. In polling, the CPU constantly checks the status of a peripheral in a loop, which is simple but wasteful of CPU cycles. An interrupt-driven design allows the peripheral to signal the CPU when an event occurs (e.g., a character received, a timer overflow). The CPU then pauses its main task to execute a short Interrupt Service Routine (ISR). Implementing efficient Interrupt Service Routines (ISRs) is vital: ISRs must be kept short and fast, often just setting a flag or moving data to a buffer, leaving complex processing to the main loop. This approach leads to more responsive and power-efficient systems.

Resource Management involves careful consideration of where variables are stored (stack, heap, or global memory). Dynamic memory allocation (malloc, free) is generally avoided in small MCUs due to the risk of fragmentation and non-deterministic timing. Instead, static or stack allocation is preferred. Understanding variable scope (static keyword for file-local persistence) and using const and volatile qualifiers correctly (volatile for variables changed outside program flow, like by an ISR) is essential for correct program behavior.

Part 3: Real-World Applications and Development Ecosystem

The application of C in MCU programming spans virtually every industry. In consumer electronics, it controls the logic in smart watches, remote controls, and home appliances. The automotive industry relies on it for engine control units (ECUs), sensor interfaces, and infotainment systems where real-time performance is critical. Industrial automation uses C-programmed MCUs for motor control, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), and monitoring systems. In the Internet of Things (IoT), C is used to write firmware for sensor nodes that collect data and communicate via wireless protocols like Bluetooth Low Energy or LoRaWAN.

The development workflow typically involves: 1. Writing code in an IDE (e.g., Eclipse-based platforms, Keil µVision) or a text editor. 2. Cross-compiling the C code on a host computer (like a PC) to generate executable hex/binary files for the target MCU. 3. Flashing/Debugging the code onto the MCU using a programmer/debugger hardware (like ST-Link for ARM Cortex-M or JTAG tools). 4. Testing and validation using logic analyzers, oscilloscopes, and serial monitors.

For developers seeking comprehensive resources—from tutorials on fundamental concepts to advanced project guides spanning various MCU architectures—platforms like ICGOODFIND serve as valuable aggregators. Such platforms can help engineers efficiently locate quality components development boards reference designs and community insights accelerating the learning curve and project execution in the vast landscape of embedded C development

Conclusion

The C programming language remains an indispensable tool in the MCU developer’s arsenal. Its unique combination of hardware control efficiency compact code generation and portability makes it perfectly suited for the demanding environment of embedded systems Success in this field hinges on more than just coding proficiency it requires a deep understanding of microcontroller architecture disciplined modular design patterns and adept handling of interrupts and direct hardware manipulation As technology evolves with more complex IoT devices and intelligent edge computing nodes the foundational skills of C programming for MCUs will continue to be highly relevant empowering engineers to build the next generation of smart connected and efficient electronic devices The journey from writing a simple LED blink program to architecting a complex real time system is challenging yet immensely rewarding solidifying C’s role as the enduring bridge between software concepts and physical hardware interaction.