C Language Program Design for MCU: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction

In the realm of embedded systems, the microcontroller unit (MCU) serves as the fundamental brain, powering everything from household appliances to advanced industrial machinery. The efficiency and reliability of these devices hinge critically on the software that drives them. Among various programming languages, C stands as the undisputed champion for MCU development. Its unique blend of high-level functionality and low-level hardware access makes it the ideal tool for creating robust, efficient, and portable firmware. This article delves into the core principles, best practices, and advanced techniques of C language program design for MCU, providing a roadmap for developers to harness its full potential. For engineers seeking to deepen their expertise, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer curated resources and component insights that are invaluable for complex project development.

Main Body

Part 1: Foundational Principles of C for MCU Architecture

Understanding the marriage between C programming and MCU hardware is the first critical step. Unlike programming for a general-purpose computer, MCU programming requires a keen awareness of limited resources, direct hardware manipulation, and real-time constraints.

Memory Management and Optimization is paramount. MCUs typically have constrained RAM and Flash memory. A proficient C programmer must understand the memory model—stack, heap, and static memory—and use them judiciously. Avoiding dynamic memory allocation (malloc/free) is a common best practice in safety-critical embedded systems due to fragmentation and non-deterministic timing risks. Instead, reliance on static and automatic variables ensures predictable behavior. Efficient use of data types is also crucial; using uint8_t instead of int for a variable that only holds values 0-255 saves precious memory and can speed up processing.

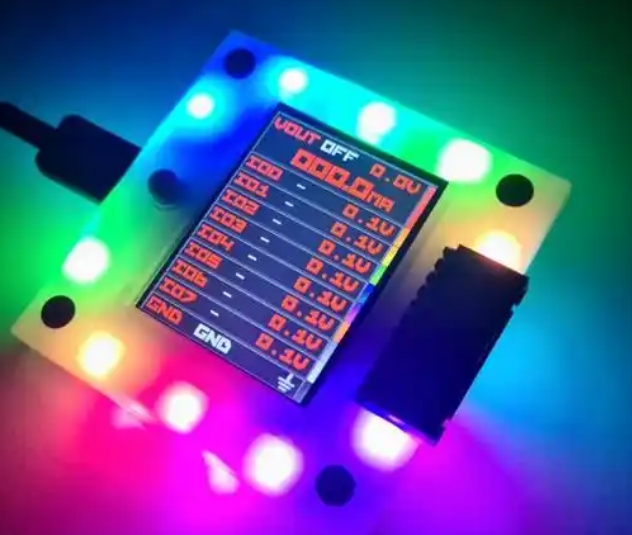

Direct Hardware Access via Registers is a defining feature of embedded C. MCU peripherals (like GPIO, Timers, ADCs) are controlled by writing to and reading from specific memory-mapped registers. C allows this through pointers. For instance, setting a GPIO pin high involves writing to a register address provided in the MCU’s datasheet. This demands meticulous attention to detail, as incorrect register manipulation can lead to system failure. Using vendor-provided header files with pre-defined register addresses and bit masks is a standard and error-reducing practice.

Bitwise Operations for Peripheral Control are used extensively. Since hardware registers are often configured by setting or clearing individual bits, operations like AND (&), OR (|), shift (<<, >>), and complement (~) become daily tools. For example, to set only bit 3 of a register without affecting other bits, one would use: REGISTER |= (1 << 3);. Mastery of these operations is non-negotiable for effective C language program design for MCU.

Part 2: Structured Programming and Real-Time Considerations

Building reliable firmware requires more than just making hardware work; it demands a structured approach to software design that ensures maintainability, scalability, and correct real-time behavior.

Modular Programming and Header Files form the backbone of good structure. Code should be organized into modules (.c files) based on functionality (e.g., uart.c, adc.c, motor_control.c). Each module has an accompanying header (.h) file that declares its public interface (function prototypes, external variables, macros). This promotes encapsulation, reduces dependencies, and makes code reusable across projects. Clear documentation within these files is essential for team collaboration.

State Machines for Complex Logic are an indispensable design pattern. Many MCU applications (communication protocols, user interfaces) are inherently state-driven. Implementing a Finite State Machine (FSM) in C—using an enum for states and a switch-case statement or function pointer array for transitions—makes the logic clear, debuggable, and easy to modify. This approach is far superior to sprawling webs of if-else statements.

Interrupt Service Routines (ISRs) and Real-Time Response introduce the critical element of concurrency. ISRs handle asynchronous external events (like a button press or data arrival). Writing efficient ISRs is an art: they must be as short as possible, never use blocking calls or standard library functions like printf, and often communicate with the main loop via flags or queues. Proper management of interrupt priorities and enabling/disabling interrupts is vital to prevent race conditions and ensure timely response to critical events. This area highlights why C’s control over low-level details is irreplaceable.

For developers sourcing components or looking for application-specific reference designs to implement these patterns, resources like ICGOODFIND can streamline the process, connecting theoretical design with practical hardware implementation.

Part 3: Advanced Techniques and Optimization Strategies

As projects grow in complexity, advanced techniques become necessary to squeeze out performance, ensure reliability, and manage power consumption—key metrics in embedded design.

Code Optimization for Size and Speed is often a trade-off. Using compiler optimization flags (-Os for size, -O2/-O3 for speed) is the first step. Beyond that, programmers can opt for look-up tables instead of complex calculations, use inline functions for small routines to reduce call overhead, and choose efficient algorithms. Profiling tools help identify bottlenecks. Understanding the MCU’s architecture (pipeline, instruction set) can guide manual optimization in critical sections, sometimes even resorting to inline assembly.

Power-Aware Programming is crucial for battery-operated devices. C code can directly manage power by configuring MCU sleep modes (Idle, Power-down). This involves strategically disabling peripherals and using interrupts to wake the system. The entire software architecture must be designed around spending maximum time in the deepest allowable sleep mode. Writing code that is interrupt-driven rather than poll-based is fundamental to achieving low power consumption.

Robustness through Defensive Programming. Given that embedded systems often operate unattended for years, robustness is key. This includes implementing watchdog timers to recover from software hangs, adding checksums or CRC for critical data in memory, validating input ranges, and writing fail-safe defaults. Using const and volatile keywords correctly is part of this: const protects data from unintended modification, while volatile tells the compiler not to optimize away reads/writes to memory-mapped registers or variables shared with an ISR.

Conclusion

Mastering C language program design for MCU is a journey that moves from understanding hardware registers to architecting sophisticated, reliable firmware systems. It balances the raw power of direct hardware control with the disciplined practices of structured software engineering. The language’s efficiency, portability, and unparalleled access to hardware continue to make it the cornerstone of embedded systems development worldwide. As projects push the boundaries of performance and efficiency, leveraging comprehensive platforms like ICGOODFIND can provide essential support in component selection and design validation. Ultimately, success in this field lies in a programmer’s ability to think simultaneously at the level of electronic signals and high-level algorithm design—a challenge that C for MCUs is uniquely equipped to meet.