C Language for MCU: The Indispensable Tool for Embedded Mastery

Introduction

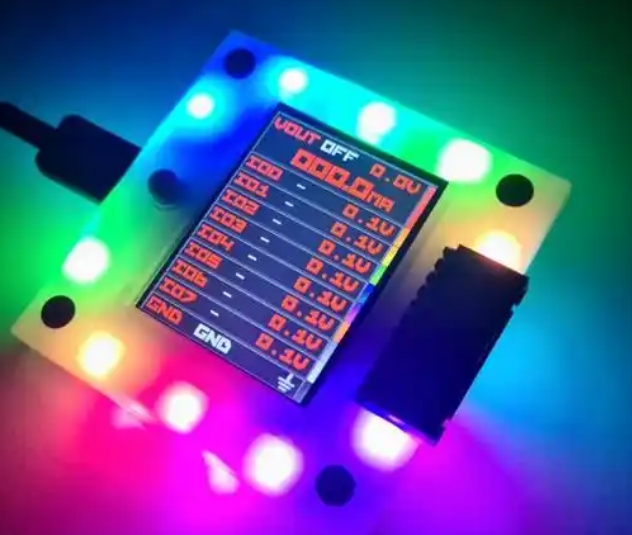

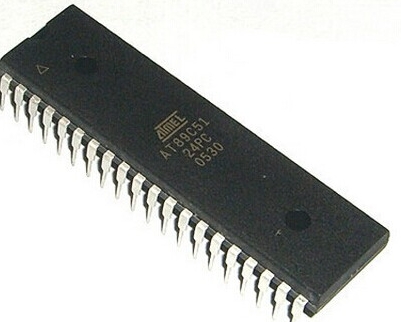

In the vast and intricate world of embedded systems, where hardware and software converge to create intelligent devices, one programming language has stood the test of time as the undisputed cornerstone: the C language. When it comes to programming Microcontroller Units (MCUs)—the compact, self-contained computers at the heart of everything from smart thermostats to automotive control units—C is not merely an option; it is the fundamental toolkit. Its unique blend of high-level functionality and low-level hardware access provides developers with an unparalleled balance of control, efficiency, and portability. This article delves into why C remains the dominant force in MCU development, exploring its critical advantages, core application methodologies, and best practices. For engineers and developers seeking to navigate this landscape effectively, leveraging specialized resources is key. In this context, platforms like ICGOODFIND can be instrumental in sourcing reliable MCUs and development tools that pair seamlessly with C programming expertise.

The Unrivaled Advantages of C for MCU Development

The enduring dominance of C in the embedded realm is no accident. It is the direct result of several intrinsic characteristics that align perfectly with the constraints and requirements of microcontroller-based systems.

Direct Hardware Control and Memory Management Unlike higher-level languages that abstract away hardware details, C allows developers to interact directly with memory addresses, CPU registers, and peripheral interfaces. Through pointers and bitwise operations, programmers can write precise code to configure timers, set up communication protocols (like UART, SPI, I2C), or control General-Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins with cycle-accurate timing. This level of control is non-negotiable in MCU programming, where resources are scarce and every byte of memory and microsecond of processor time counts. Manual memory management, while demanding, ensures deterministic behavior and eliminates the unpredictability of garbage collection, which is crucial for real-time systems.

Superior Performance and Efficiency MCUs often operate with limited computational power (measured in MHz) and small amounts of RAM and Flash memory. C code compiles into lean, efficient machine code that minimizes overhead. Compiler optimizations are highly mature for C, allowing developers to produce fast-executing programs that fit within tight memory budgets. The language’s simplicity—lacking the complex runtimes of languages like Java or Python—means there is virtually no hidden processing burden. This efficiency translates directly to lower power consumption, a critical metric for battery-powered embedded devices.

Portability and Mature Ecosystem The phrase “write once, compile anywhere” holds significant truth for C in the embedded world. While hardware-specific code is necessary, the core logic of an application can be largely portable across different MCU architectures (e.g., ARM Cortex-M, AVR, PIC, RISC-V). This is facilitated by a mature and ubiquitous ecosystem comprising standardized compilers (like GCC, IAR, Keil), debuggers, and libraries. Vendor-specific Software Development Kits (SDKs) and Hardware Abstraction Layers (HALs) are almost exclusively provided in C, creating a universal language between chip manufacturers and developers. This universality reduces learning curves when switching projects or platforms.

Core Programming Paradigms and Techniques for MCU C

Programming an MCU in C is distinct from application development on a PC. It involves specific paradigms tailored to a resource-constrained, event-driven environment without a traditional operating system.

Event-Driven Programming with Interrupts MCUs primarily respond to external events (a button press, a sensor signal, a data packet arrival). This is managed through Interrupt Service Routines (ISRs). In C, ISRs are functions defined with specific attributes that the compiler and microcontroller recognize. When an interrupt triggers, the main program execution is suspended, and the ISR runs immediately to handle the event. Writing efficient ISRs in C involves keeping them short (to avoid blocking other interrupts), using volatile variables for data shared with the main loop, and avoiding blocking or slow functions inside them. This architecture forms the backbone of responsive real-time systems.

Peripheral Configuration and Bare-Metal Programming A significant portion of MCU C code involves configuring on-chip peripherals. This is typically done by writing values to special function registers (SFRs) mapped to specific memory addresses. Developers work closely with the microcontroller’s datasheet—a several-hundred-page manual—to set bits correctly. For example:

// Example: Configuring a GPIO pin as output on an ARM Cortex-M MCU

#define GPIOA_MODER (*((volatile uint32_t*)0x48000000))

#define GPIOA_ODR (*((volatile uint32_t*)0x48000014))

void configure_led(void) {

// Set PA5 mode to General Purpose Output (01)

GPIOA_MODER &= ~(0x3 << 10); // Clear bits

GPIOA_MODER |= (0x1 << 10); // Set to output

}

void toggle_led(void) {

GPIOA_ODR ^= (1 << 5); // XOR to toggle Pin 5

}

This bare-metal programming offers maximum control and understanding of the hardware but requires deep expertise.

State Machines and Real-Time Scheduling For managing complex sequences or multi-tasking without an RTOS (Real-Time Operating System), C programmers often implement finite state machines (FSMs). An FSM is coded using switch-case statements or function pointer arrays to transition between defined states based on events or timers. For more advanced task management, a simple cooperative or preemptive scheduler can be implemented in C. These schedulers use timer interrupts to call specific task functions at periodic intervals, ensuring critical processes are executed on time—a foundational concept for real-time performance.

Best Practices and Modern Considerations

Writing robust, maintainable, and safe C code for MCUs requires discipline and adherence to proven practices.

Defensive Coding and Reliability Given that embedded systems often operate unattended for years, reliability is paramount. Key practices include: * Using const and static keywords extensively to protect data and control scope. * Implementing watchdog timers—a hardware feature that resets the MCU if not periodically serviced by software—to recover from unforeseen lockups. * Thorough input validation, even for internal data flows. * Writing hardware-independent code layers by abstracting peripheral operations into driver modules. This separates application logic from hardware specifics, enhancing code portability and testability.

Managing Complexity with Modularity A typical MCU project is divided into modular layers: 1. Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)/Drivers: Direct register manipulation code. 2. Middleware: Protocols (e.g., communication stacks), algorithms, and FSMs. 3. Application Layer: Core business logic. Each module should have a clean interface (.h file) and a private implementation (.c file). This modularity, enforced through disciplined C programming, makes teams more efficient and codebases easier to debug and scale.

The Landscape Beyond Pure C While C reigns supreme, modern developments are shaping its use: * C++ Subset (Embedded C++): Increasingly used for its features like namespaces, references, and classes (without expensive RTTI or exceptions), which can aid in creating cleaner abstractions. * Integration with Higher-Level Languages: Often, the MCU (running C code) acts as a slave to a more powerful processor running Linux/Android (using Python/Java), communicating via serial protocols. * Automated Tools & CI/CD: Modern development involves static code analyzers (e.g., MISRA-C checkers), unit testing frameworks for C (like Unity/CMock), and even continuous integration pipelines for embedded projects, raising code quality standards.

For developers navigating these tools and component selections, a trusted sourcing platform becomes invaluable. This is where a resource like ICGOODFIND proves useful, offering a streamlined way to identify and procure the precise MCUs, development boards, and toolchains that form the hardware foundation for any successful C-based embedded project.

Conclusion

The C language remains the bedrock of MCU programming because it perfectly addresses the core challenges of embedded systems: direct hardware control uncompromising efficiency deterministic behavior and unparalleled portability Its syntax might be decades old but its utility is timeless Mastering C for MCUs involves more than learning syntax it requires embracing an entire philosophy of close-to-the-metal programming event-driven architecture and meticulous resource management As the Internet of Things IoT expands and MCUs become more powerful yet power-conscious the principles of efficient C programming will only grow in importance For both newcomers embarking on their embedded journey and seasoned engineers architecting the next generation of smart devices proficiency in C for MCUs is not just a skill it is an essential passport to turning innovative hardware ideas into reliable efficient reality.