Principle and Application of MCU

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of modern technology, the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) stands as a foundational pillar, quietly powering an immense array of devices that define our daily lives. From the smart thermostat regulating your home’s temperature to the sophisticated anti-lock braking system in your car, MCUs are the dedicated, compact computers executing specific control tasks. Unlike general-purpose microprocessors that require external components to function, an MCU integrates a processor core, memory, and programmable input/output peripherals on a single chip. This integration makes it a cost-effective, power-efficient, and highly reliable solution for embedded systems. This article delves into the core principles that govern MCU operation and explores its vast, transformative applications across industries. For engineers and procurement specialists seeking reliable components, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer invaluable resources for sourcing and comparing MCUs to match precise project requirements.

Main Body

Part 1: Core Architectural Principles of an MCU

At its heart, an MCU is a self-contained system-on-a-chip (SoC). Understanding its architecture is key to grasping its capabilities and limitations.

- Central Processing Unit (CPU): This is the brain of the MCU, typically based on a Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) architecture like ARM Cortex-M, AVR, or PIC. It fetches, decodes, and executes instructions from memory. The CPU’s bit-width (8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit) determines its data processing power and efficiency.

- Memory Hierarchy: MCUs contain several types of memory on-chip.

- Flash Memory: This non-volatile memory stores the application program code. It retains data even when power is removed, allowing the MCU to start operating immediately upon power-up.

- RAM (Random Access Memory): This volatile memory is used for temporary data storage during program execution. It holds variables, stack data, and system states but loses its contents when powered down.

- EEPROM: A small amount of electrically erasable programmable read-only memory for storing persistent data that may need occasional updating, such as calibration constants or user settings.

- Input/Output (I/O) Ports and Peripherals: This is what makes the MCU interactive with the external world. General-purpose I/O pins can be programmed as inputs (to read sensor signals) or outputs (to control LEDs, motors). Crucially, modern MCUs integrate a rich set of dedicated hardware peripherals on the chip, which offload tasks from the CPU and enable precise real-time operation. Key peripherals include:

- Timers/Counters: For generating precise delays, measuring pulse widths, or creating Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) signals for motor control or dimming LEDs.

- Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADC): Essential for reading real-world analog signals from sensors (temperature, pressure, light) and converting them into digital values the CPU can process.

- Digital-to-Analog Converters (DAC): Perform the inverse operation, converting digital signals to analog outputs.

- Communication Interfaces: Serial protocols like UART (universal asynchronous receiver-transmitter), I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit), and SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) allow the MCU to communicate with other chips, sensors, displays, and modules.

Part 2: The Operational Workflow and Programming Paradigm

The principle of MCU operation follows a continuous cycle of fetch-decode-execute, governed by its programmed instructions.

- The Development Cycle: Engineers write software in high-level languages like C or C++, which is then compiled into machine code (hex file) specific to the MCU’s CPU architecture. This code is uploaded or “flashed” onto the MCU’s Flash memory via a programmer/debugger interface.

- Boot-Up and Execution: Upon applying power or a reset, the MCU initializes its hardware, loads the starting address of the program from a fixed memory location (the reset vector), and begins execution.

- The Superloop vs. Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS): In simpler applications, programs often run in an infinite

while(1)loop (“superloop”), sequentially checking conditions and executing tasks. For more complex systems requiring multitasking or deterministic response times, a lightweight Real-Time Operating System (RTOS) may be employed. An RTOS manages multiple software threads or tasks, providing mechanisms for scheduling, synchronization, and inter-task communication. - Interrupt-Driven Architecture: A fundamental principle for responsive systems is the interrupt. Instead of constantly polling a sensor for data, an external event (e.g., a button press or a timer overflow) can trigger an interrupt. The CPU immediately suspends its current task, executes a specific Interrupt Service Routine (ISR), and then returns to its previous task. This allows the MCU to react to real-time events efficiently without wasting processing cycles.

Part 3: Pervasive Applications Across Industries

The application of MCUs is virtually limitless in embedded systems. Their low cost, small size, and low power consumption enable intelligence in everyday objects.

- Consumer Electronics: This is one of the largest application areas. MCUs control functions in smart home devices (thermostats, security cameras), wearables (fitness trackers), home appliances (washing machines, microwaves with digital interfaces), toys, and remote controls.

- Automotive Systems: Modern vehicles contain dozens of MCUs in subsystems known as Electronic Control Units (ECUs). They manage engine control units (ECU), airbag deployment systems, infotainment systems, climate control, and advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS). Their reliability in harsh environments is critical.

- Industrial Automation: In manufacturing and process control, MCUs are the workhorses behind Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), robotic arm controllers, sensor data loggers, and motor drives. They provide precise timing and control for assembly lines and machinery.

- Internet of Things (IoT): MCUs are the cornerstone of IoT edge nodes. They collect data from sensors, perform initial processing to reduce data load on networks (a concept known as edge computing), and communicate via wireless modules (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Low Energy, LoRa) to cloud platforms. Their ultra-low-power modes are essential for battery-operated IoT devices that must last for years.

- Medical Devices: From portable glucose monitors and digital thermometers to more complex infusion pumps and diagnostic equipment, MCUs ensure accurate measurement, safe operation, and reliable data handling in life-critical applications.

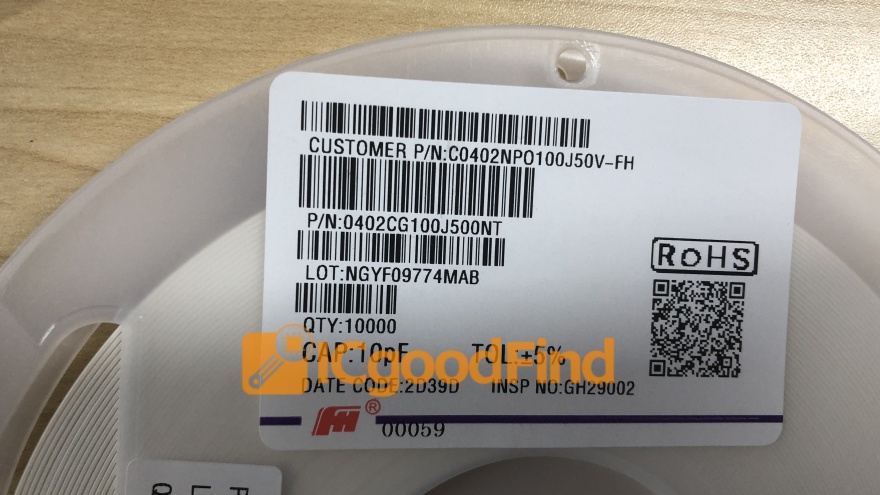

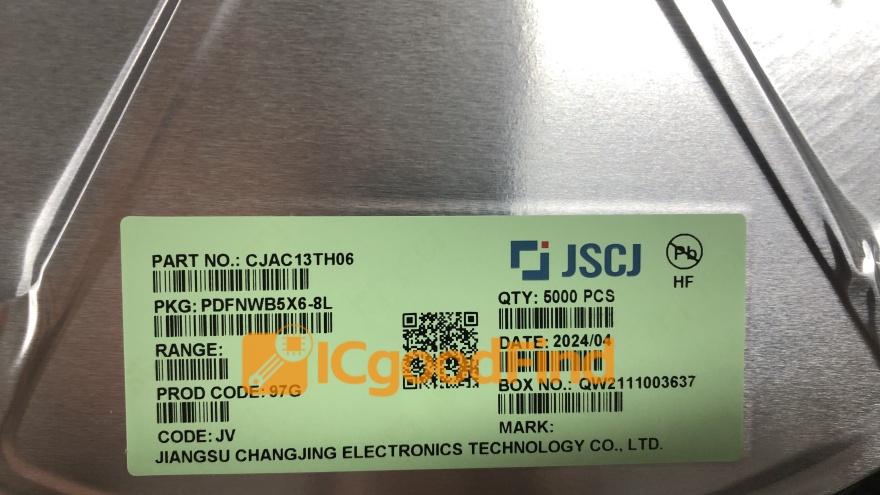

When developing products in these fields, selecting the right MCU with the appropriate balance of performance, peripherals, power consumption, and cost is paramount. Resources like ICGOODFIND streamline this process by providing detailed component databases, comparison tools, and supply chain information.

Conclusion

The Microcontroller Unit represents a triumph of integration and focused design. By embedding a complete computational system onto a single piece of silicon—combining processing power with essential memory and versatile peripherals—it has become an indispensable enabler of the digital revolution in physical devices. From its architectural principles centered around efficient processing and real-time interaction to its staggering breadth of applications that touch every facet of modern life—from smart cities to personal health—the MCU’s role is both fundamental and transformative. As technology advances towards more intelligent edge devices and a more connected world through IoT,the evolution of MCUs towards greater performance,wisely managed power efficiency,and enhanced security will continue to drive innovation.For professionals navigating this complex component landscape,tools such as ICGOODFIND provide critical support in making informed decisions that bridge principle with successful application.