MCU Programming Languages: Choosing the Right Tool for Embedded Development

Introduction

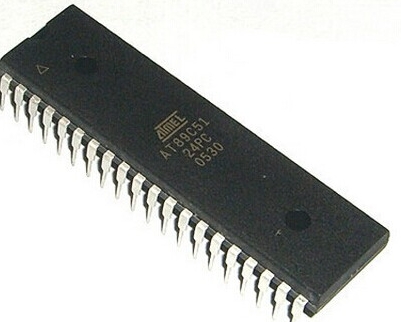

In the intricate world of embedded systems, the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) serves as the silent, powerful brain behind countless devices—from smart home gadgets and wearable tech to industrial automation and automotive control systems. While hardware specifications like clock speed, memory, and I/O pins are critical, the choice of programming language fundamentally shapes the development process, performance, and capabilities of the final product. Unlike general-purpose computing, MCU programming operates under stringent constraints of limited resources, real-time requirements, and direct hardware manipulation. This article delves into the landscape of MCU programming languages, examining their unique strengths, ideal use cases, and how they empower developers to bridge the gap between abstract code and physical interaction. As the Internet of Things (IoT) and edge computing continue to expand, making an informed decision about your programming language is more crucial than ever for creating efficient, reliable, and innovative embedded solutions.

The Core Contenders: C, C++, and Assembly

The foundation of MCU programming is built upon a few established languages, each offering a distinct balance of control, abstraction, and efficiency.

C Language: The Unrivaled Standard For decades, C has been the dominant force in MCU development. Its enduring popularity stems from a powerful combination of features perfectly suited to embedded environments. C provides “high-level” functionality like structured programming and functions while maintaining “low-level” access to memory and hardware registers through pointers. This allows developers to write code that is both relatively readable and extremely efficient in terms of execution speed and memory footprint—a non-negotiable requirement for resource-constrained MCUs. Most MCU vendors supply their Hardware Abstraction Layers (HALs), drivers, and toolchains primarily in C, ensuring extensive compiler support and a vast ecosystem of libraries and community knowledge. Its procedural nature encourages a close mental model of the hardware’s operation, making it ideal for time-critical routines and direct peripheral control.

C++: Object-Oriented Power with Caution C++ brings object-oriented programming (OOP), templates, and richer abstractions to the embedded realm. When used judiciously, C++ features like classes, encapsulation, and RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization) can significantly improve code organization, reusability, and safety for complex projects. Modern C++ compilers for MCUs have improved, allowing the use of a subset of the language (often called “embedded C++”) that avoids expensive features like exceptions and heavy use of the Standard Template Library (STL). This enables developers to model complex system states more intuitively while still generating tight machine code. However, developers must be vigilant about avoiding hidden overheads in dynamic memory allocation, virtual functions, or RTTI (Run-Time Type Information) that can bloat code size and introduce unpredictable timing.

Assembly Language: Maximum Control at the Lowest Level Assembly language represents the most fundamental interface with the MCU, where code is written directly in human-readable mnemonics corresponding to the processor’s instruction set. Its primary use in modern development is for optimizing ultra-critical sections of code or accessing esoteric processor features unavailable through higher-level languages. While writing an entire application in assembly is rare today due to immense development time and maintenance challenges, understanding assembly is invaluable for debugging, reading compiler output, and truly comprehending how software interacts with silicon. It remains the ultimate tool for squeezing out every last cycle of performance or byte of memory.

Emerging and Specialized Languages

The landscape is evolving with languages that offer new paradigms aimed at improving productivity, safety, and connectivity.

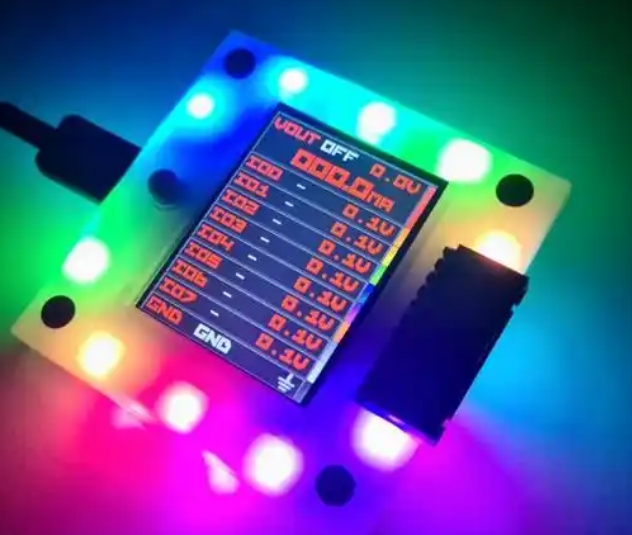

MicroPython and CircuitPython: Python on Microcontrollers These implementations bring the simplicity and readability of Python to the MCU world. They enable rapid prototyping, iterative development, and lower the barrier to entry for beginners and professionals alike by offering an interactive REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) and high-level data structures. While interpreted languages incur a performance and memory overhead compared to compiled C/C++, they are perfectly suited for applications where development speed is paramount or where the hardware capability (like a more powerful Cortex-M4 or M7 chip) can accommodate the interpreter. They are particularly popular in education, hobbyist projects, and for crafting complex device logic where raw speed is less critical than clear, maintainable code.

Rust: The Modern Challenger for Safety and Performance Rust is rapidly gaining traction in embedded systems as a compelling alternative to C/C++. Its core promise is providing C-level performance and control while guaranteeing memory safety at compile time through its innovative ownership model, eliminating entire classes of bugs like null pointer dereferencing, buffer overflows, and data races—common pitfalls in traditional embedded programming. While its learning curve is steep, Rust offers fearless concurrency, modern tooling (Cargo), and growing support for major MCU architectures through projects like embedded-hal. It represents a strategic choice for projects where reliability, security, and long-term maintainability are top priorities.

Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs) and Visual Tools Beyond textual languages, various DSLs and graphical programming environments exist. Languages like Lustre or SCADE, used in safety-critical industries (avionics, automotive), are based on synchronous data-flow paradigms. Visual modeling tools (e.g., Simulink/Stateflow) allow developers to design system logic with block diagrams or state charts, which are then automatically generated into C code. These approaches formalize design patterns and can automatically handle complex tasks like task scheduling or ensuring deterministic execution, though they often come with vendor toolchain dependencies.

Choosing Your Language: Key Decision Factors

Selecting the right language is not about finding the “best” one universally, but the most appropriate one for your specific project context.

Project Requirements & Constraints The nature of the project dictates core needs. For bare-metal programming or real-time operating systems (RTOS) where deterministic timing and minimal latency are critical, C remains the default choice. For complex applications involving networking stacks, GUI elements, or sophisticated algorithms where code structure becomes paramount, a subset of C++ or Rust may offer better long-term manageability. For proof-of-concepts, educational tools, or applications where connectivity logic is more complex than low-level hardware twiddling, MicroPython can accelerate development cycles dramatically.

Team Expertise & Ecosystem Support The existing skillset of your development team is a massive practical consideration. Introducing a new language like Rust requires significant investment in training. Furthermore, the availability of libraries (for drivers, communication protocols, etc.), mature debugging tools (like JTAG/SWD debuggers integrated with the IDE), stable compiler support for your target MCU architecture are often decisive factors. A language with a vibrant community can drastically reduce development hurdles when facing obscure hardware issues.

Performance vs. Productivity Trade-off This is the central tension in embedded development. Assembly offers maximum performance but lowest productivity; C offers an excellent balance; higher-level languages boost productivity at a potential cost in runtime efficiency and memory usage. The key is to profile your application: identify the 5% of code that consumes 95% of processing time or triggers timing deadlines. This critical path might be written in C or even hand-optimized assembly, while the rest of the application could leverage the productivity benefits of C++ or even a DSL.

Conclusion

The world of MCU programming languages is rich and varied, extending far beyond the traditional realm of C alone. From the unyielding control of Assembly and the balanced prowess of C to the structured abstraction of C++, the accessibility of MicroPython, and the safe concurrency of Rust—each language serves as a different lens through which to solve embedded challenges. The optimal choice hinges on a careful analysis of your project’s performance requirements, resource limits, team dynamics, and long-term maintenance goals. There is no universal “winner,” but rather a strategic selection process that aligns language capabilities with project demands. As MCUs grow more powerful and connected systems more complex this thoughtful selection becomes a cornerstone of successful product development For developers seeking to navigate this complex landscape efficiently resources that curate tools libraries tutorials across these languages can be invaluable platforms like ICGOODFIND serve as centralized hubs helping engineers quickly locate the best frameworks SDKs reference designs specific to their chosen language-MCU combination thereby accelerating innovation from concept to deployment By mastering both classical modern languages embedded engineers equip themselves build next generation intelligent reliable devices define our interconnected world.