China Chip Procurement Network: Navigating the New Frontier in Global Tech

Introduction

The global technology landscape is undergoing a seismic shift, with semiconductor chips sitting firmly at its epicenter. These tiny silicon components, often no larger than a fingernail, have become the lifeblood of modern civilization, powering everything from smartphones and laptops to critical infrastructure, military systems, and the burgeoning artificial intelligence sector. In this high-stakes environment, China’s ambitious drive to secure a stable and advanced supply of semiconductors has given rise to a sophisticated and often misunderstood ecosystem: the China Chip Procurement Network. This network is not a single entity but a complex, multi-layered web of state-directed initiatives, private enterprises, and strategic global partnerships. Its primary objective is to circumvent technological bottlenecks and ensure the technological self-reliance and continued economic growth of the world’s second-largest economy. Understanding this network is crucial for comprehending the future of global tech competition, supply chain dynamics, and geopolitical tensions. This article delves into the mechanics, drivers, and global implications of China’s relentless pursuit of semiconductor sovereignty.

The Anatomy and Strategic Imperative of the Network

The China Chip Procurement Network is a testament to strategic national planning. Its formation and evolution are driven by a clear recognition of a critical vulnerability: China’s heavy reliance on foreign chip technology, particularly from the United States, Taiwan, and South Korea. This reliance was identified as a significant national security and economic risk, leading to the launch of ambitious state-led programs like “Made in China 2025,” which explicitly targeted dominance in high-tech industries, including semiconductors.

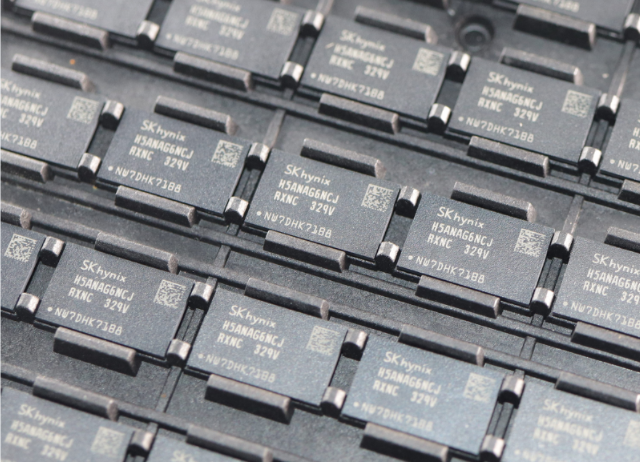

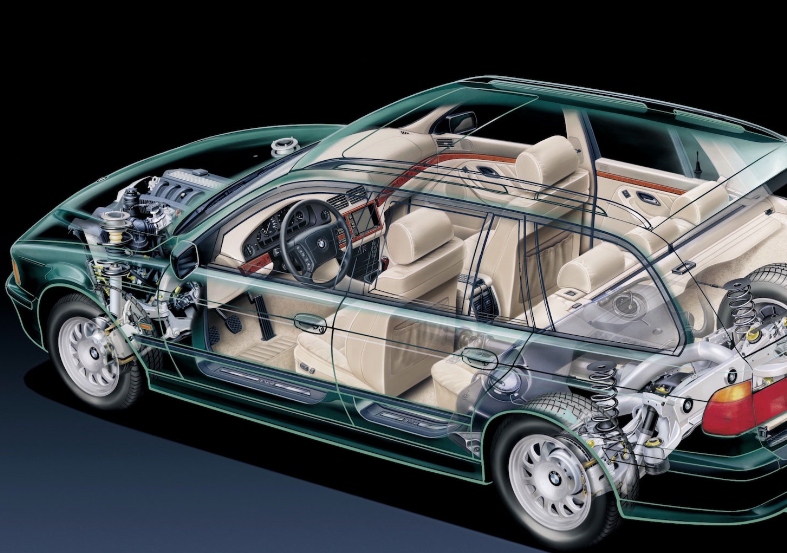

At its core, the network operates on multiple, interconnected levels. The most visible layer consists of China’s tech giants—companies like Huawei, SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation), and CXMT (ChangXin Memory Technologies). These companies are on the front lines, engaging in global markets to purchase chip manufacturing equipment (CPUs, GPUs, etching machines from ASML, Applied Materials, etc.), licensing intellectual property (IP), and acquiring raw materials like high-purity silicon. Their procurement activities are massive in scale and essential for keeping China’s consumer electronics and industrial machinery running.

Beneath this corporate layer lies a framework of substantial financial support and policy guidance. The National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, colloquially known as the “Big Fund,” is a cornerstone of this effort. With tens of billions of dollars at its disposal, the Big Fund directly invests in domestic chip designers, manufacturers, and equipment suppliers. This state-backed capital de-risks expensive R&D and capital expenditure, enabling Chinese firms to compete in a sector where building a single fabrication plant (fab) can cost over $20 billion. This financial muscle is a defining feature of the China Chip Procurement Network, allowing it to pursue long-term goals that would be untenable for purely commercial entities.

Furthermore, the network extends into the realm of talent acquisition and knowledge transfer. China has actively recruited top-tier semiconductor engineers and scientists from around the world, offering lucrative packages to bring expertise home. Joint ventures with foreign firms have also been a key tactic, serving as a conduit for technology transfer before the partners often become competitors. This multi-pronged approach—combining corporate procurement, state capital, and intellectual horsepower—demonstrates a comprehensive strategy to build an end-to-end domestic semiconductor industry, from design and materials to manufacturing and packaging.

Navigating Geopolitical Headwinds and Sanctions

The aggressive expansion of the China Chip Procurement Network has not gone unnoticed or unchallenged. The United States, citing national security concerns, has enacted a series of escalating export controls and sanctions designed to cripple China’s ability to procure advanced chips and the tools to make them. These measures represent the most significant external pressure on the network, forcing a dramatic recalibration of its strategies.

The U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has placed major Chinese tech firms like Huawei and SMIC on its Entity List, severely restricting their ability to buy U.S.-origin technology. More sweeping regulations introduced in October 2022 further cut off China’s access to advanced AI chips and chip-making equipment. The goal is clear: to create a “chokepoint” that slows down China’s technological progress, particularly in areas with military applications like supercomputing and AI development. In response, the China Chip Procurement Network has had to become more resilient and clandestine.

One key adaptation is the intensified focus on developing domestic capabilities. With access to cutting-edge extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines from ASML blocked, Chinese entities are pouring resources into homegrown alternatives. While still years behind, companies like SMEE (Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment) are making incremental progress in developing deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography systems. The network is also fostering a domestic ecosystem for chip design tools (EDA), a field long dominated by American companies.

Another adaptation is supply chain diversification and the use of indirect procurement channels. The network increasingly relies on intermediaries in other countries to acquire restricted goods, a practice that complicates enforcement for regulators. There is also a strategic stockpiling of critical equipment and chips ahead of anticipated sanctions. Furthermore, Chinese firms are exploring collaborations with other regions less aligned with U.S. policy. For professionals and analysts trying to make sense of these complex, real-time shifts in global tech supply chains, platforms like ICGOODFIND can be an invaluable resource for tracking component availability, market trends, and emerging procurement pathways.

The Global Impact and Future Trajectory

The activities of the China Chip Procurement Network are reshaping global trade, technology standards, and international relations. Its persistence has effectively bifurcated the global technology ecosystem, leading to the potential emergence of parallel supply chains: one centered on the U.S. and its allies, and another catering to China and its partners.

For global chip companies, this creates a precarious balancing act. Firms like NVIDIA, AMD, and TSMC generate significant revenue from the Chinese market but must carefully navigate U.S. restrictions by creating modified, compliant versions of their products. This dynamic creates uncertainty and inefficiency in one of the world’s most globalized industries. For other countries, particularly in Asia and Europe, it forces difficult choices between economic ties with China and strategic alignment with the U.S.

Looking forward, the network’s trajectory will be defined by its success or failure in achieving technological breakthroughs. If it can successfully indigenize production of advanced nodes (e.g., 7nm and below), it would mark a monumental achievement and significantly reduce its external vulnerabilities. However, this remains an enormous challenge due to the immense complexity and interconnected nature of semiconductor technology.

The more likely scenario in the near to medium term is a continued “cat-and-mouse” game between procurement efforts and export controls. China will continue to leverage its market size as a bargaining tool and invest heavily in legacy node production (28nm and above), which still caters to the vast majority of electronics demand, including for electric vehicles and smart appliances. The network will also likely deepen its ties with other countries as part of initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative, creating alternative technological corridors that are less susceptible to Western pressure.

Conclusion

The China Chip Procurement Network is far more than a simple buying operation; it is a central pillar of China’s national strategy for technological sovereignty and global influence. Born from a perceived strategic vulnerability, it has matured into a sophisticated system integrating state capital corporate ambition,and global supply chain tactics.Its evolution is now locked in a tight feedback loop with geopolitical contestation particularly with the United States.As export controls tighten,the network adaptsbecoming more resilient focused on self-sufficiencyand exploring new avenues for procurement.This struggle for chip supremacy is defining the new era of techno-nationalismwith profound implications for global economic stability international securityand the future pace of innovation.Understanding the mechanismsand motivations of this network is therefore not just an academic exercise but a necessity for anyone engaged in the global technology industry or international policy.