Materials of Electronic Components: The Foundation of Modern Technology

Introduction

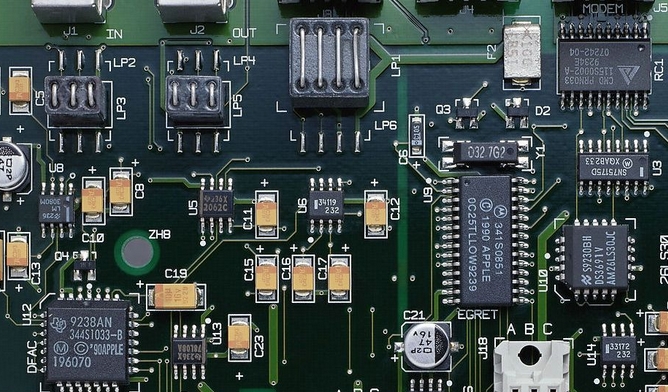

The intricate world of electronic components is the bedrock upon which our modern, connected society is built. From the smartphone in your pocket to the satellites orbiting our planet, every piece of electronic equipment is a complex mosaic of individual components, each with a specific, critical function. While circuit design and software often capture the spotlight, the true unsung heroes are the materials from which these components are constructed. The performance, reliability, efficiency, and even the physical size of an electronic device are fundamentally dictated by the properties of its constituent materials. Understanding these materials is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for engineers designing the next generation of technology and for procurement specialists seeking reliable components. In this landscape, finding high-quality components made from superior materials is paramount, a task where a specialized resource like ICGOODFIND can prove invaluable by connecting professionals with trusted suppliers and detailed component data sheets. This article delves into the essential materials that form the core of electronic components, exploring their properties, applications, and the ongoing evolution that drives technological progress.

The Core Conductors: Enabling the Flow of Electricity

At the heart of every electronic circuit is the need to direct and control the flow of electrical current. This primary function is fulfilled by conductors, with metals being the most prominent category.

Copper: The Unrivaled Workhorse

Copper stands as the most ubiquitous and critical conductive material in the electronics industry. Its dominance is attributed to an exceptional combination of high electrical conductivity, excellent thermal conductivity, good ductility, and relatively low cost. The atomic structure of copper allows electrons to move with minimal resistance, making it incredibly efficient for transmitting electrical signals and power. Its applications are virtually limitless: * Printed Circuit Board (PCB) Traces: The intricate pathways on every PCB are typically made from thin layers of copper foil. * Wires and Cables: From internal wiring to external power cords, copper is the standard. * Component Leads: The legs of resistors, capacitors, and integrated circuits are often copper-based alloys. * Windings in Transformers and Inductors: Copper wire is wound into coils to create magnetic fields.

While pure copper offers the best conductivity, it is often alloyed with small amounts of other elements like tin or phosphorus to improve mechanical strength and resistance to creep for specific applications.

Precious Metals: Specialized Performance

For highly demanding or sensitive applications, more expensive materials are employed. Gold and Silver offer even higher conductivity than copper but are used selectively due to their cost. * Gold: Prized for its exceptional resistance to oxidation and corrosion, gold is indispensable for reliable electrical contacts that cannot fail over time. It is commonly used in connector pins, switch contacts, and as a bonding wire inside microchips. Its inert nature ensures a stable connection without the formation of non-conductive oxide layers. * Silver: Possessing the highest electrical conductivity of all metals, silver is used in specialized applications where performance is paramount, such as in high-frequency RF circuits and some high-end power semiconductors. Silver paste is also a key material in the electrodes of multilayer ceramic capacitors.

Aluminum: The Lightweight Alternative

Aluminum serves as a cost-effective and lightweight alternative to copper, particularly where weight is a critical factor. While its conductivity is only about 60% that of copper, its lower density makes it advantageous. Its primary use in electronics is in high-power busbars and as a conductor in large power transmission lines. Inside components, it was historically used for the bonding wires in integrated circuits, though gold has largely taken over due to better reliability.

Insulators and Semiconductors: Controlling the Current

If conductors are the highways for electrons, then insulators and semiconductors are the traffic control system—the stoplights, off-ramps, and complex interchanges that give electronics their functionality.

Semiconductor Materials: The Brain of Modern Electronics

Semiconductor materials, primarily Silicon, form the active core of nearly all modern electronic devices. Their unique property is an electrical conductivity that can be precisely controlled by introducing impurities (doping) or applying an electric field. This allows them to act as switches, amplifiers, and signal processors. * Silicon (Si): Silicon is the undisputed king of semiconductor materials, accounting for over 95% of all semiconductor devices produced. Its advantages include its abundance (sand is silicon dioxide), the ability to form a high-quality native oxide (SiO2), which is an excellent insulator, and well-understood and scalable manufacturing processes. It is the foundation for microprocessors, memory chips, transistors, and diodes. * Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) and Gallium Nitride (GaN): These are known as compound semiconductors. While more expensive and harder to manufacture than silicon, they excel in specific areas. GaAs is renowned for its high-electron mobility, making it ideal for high-frequency applications like radio frequency (RF) amplifiers in smartphones and satellite communications. GaN is a wide-bandgap semiconductor that enables high-power, high-efficiency devices used in advanced power converters, 5G infrastructure, and fast chargers. * Silicon Carbide (SiC): Another wide-bandgap semiconductor, SiC operates efficiently at very high temperatures, voltages, and frequencies. It is rapidly being adopted in electric vehicle power inverters, industrial motor drives, and renewable energy systems because it significantly reduces energy loss.

Insulating Materials: The Essential Barriers

Insulators, or dielectrics, are materials that resist the flow of electric current. They are crucial for preventing short circuits, storing electrical energy, and providing structural support. * Ceramics: Ceramic materials like alumina (Al2O3) and porcelain are valued for their high dielectric strength, excellent thermal stability, and good mechanical rigidity. They are used as substrates for PCBs in high-power applications, as the insulating body in spark plugs, and as the dielectric material in ceramic capacitors. * Plastics and Polymers: This is a vast category of insulating materials. Common examples include: * Epoxy Resin: Used to encapsulate and protect integrated circuits in a process called “packaging” or “potting.” * FR-4: A glass-reinforced epoxy laminate that is the standard material for rigid PCBs. * Polyimide: A high-performance polymer known for its thermal stability, used in flexible PCBs (e.g., in smartphones and cameras). * PVC and PE: Used as insulation for electrical wires and cables. * Silicon Dioxide (SiO2): For decades, a thin layer of silicon dioxide served as the perfect gate insulator in MOSFET transistors, enabling the entire microelectronics revolution. While newer materials like hafnium-based high-k dielectrics have replaced it at atomic scales, SiO2 remains a fundamental insulating material within chip structures.

Structural & Functional Materials: Beyond Conductivity

An electronic device is more than just its electrical pathways; it requires a physical structure and materials that perform specialized functions beyond simple conduction or insulation.

Substrate and Package Materials

Every component needs a physical foundation and protection from the environment. * PCB Laminates: As mentioned, FR-4 is common, but high-frequency applications require materials with lower dielectric loss, such as PTFE (Teflon). * Semiconductor Substrates: Pure silicon wafers are not just for building transistors; they also act as the mechanical substrate upon which entire circuits are fabricated. * Packaging Materials: These protect the delicate silicon die from moisture, contaminants, and physical damage. Materials include epoxy resins, ceramics (for high-reliability applications), and metal cans.

Magnetic Materials

These materials are essential for components that interact with magnetic fields. * Ferrites: These ceramic compounds made from iron oxide mixed with other metals are excellent magnetic conductors but poor electrical conductors, making them ideal for cores in inductors and transformers. They concentrate magnetic fields while minimizing energy losses from eddy currents. * Iron Alloys: Laminated silicon steel sheets are used in the cores of large power transformers and motors due to their high magnetic permeability.

Thermal Management Materials

As electronic devices become more powerful, dissipating waste heat becomes a critical challenge. * Thermal Interface Materials (TIMs): These include thermal greases, pads, and phase-change materials that are placed between a hot component (like a CPU) and a heat sink to improve heat transfer by filling microscopic air gaps. * Heat Sinks: Typically made from aluminum or copper due to their high thermal conductivity. Copper is superior but heavier and more expensive; aluminum offers a better performance-to-weight-cost ratio for many applications.

In navigating this complex ecosystem of materials and components—from sourcing a specific GaN transistor to finding a capacitor with a ceramic dielectric suited for a high-temperature environment—the process can be daunting. This is where leveraging a comprehensive platform becomes critical. A resource like ICGOODFIND can significantly streamline this process by providing access to a vast database of components from numerous suppliers, allowing engineers and buyers to compare specifications, availability, and datasheets to ensure they select the part built with the right materials for their specific application needs.

Conclusion

The evolution of electronics is inextricably linked to the innovation and application of advanced materials. From the humble conductivity of copper to the precisely engineered properties of silicon and gallium nitride, each material plays a vital role in defining what is technologically possible. The ongoing research into new material systems—such as graphene for ultra-high-speed transistors, organic polymers for flexible electronics, and new complex oxides for memory applications—promises to unlock even greater capabilities in the future. Understanding these fundamental building blocks is essential for anyone involved in the design, manufacture, or procurement of electronic devices. The careful selection of component materials directly impacts performance metrics like speed, power efficiency, durability, and miniaturization. As we continue to push the boundaries of technology, the quest for better, smarter, and more efficient materials will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of electronic innovation.