MCU Program Cracking: Risks, Methods, and Protection Strategies

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of embedded systems and Internet of Things (IoT) devices, the security of Microcontroller Unit (MCU) firmware stands as a critical frontier. MCU program cracking, the process of reverse-engineering or extracting proprietary code from a microcontroller’s memory, represents a significant threat to intellectual property, product integrity, and system security. This practice, often employed for both malicious and competitive intelligence purposes, exposes vulnerabilities that can lead to counterfeiting, feature theft, and even safety-critical system failures. As industries from automotive to consumer electronics become increasingly reliant on embedded intelligence, understanding the nature of this threat is paramount for developers, manufacturers, and security professionals. This article delves into the mechanisms of MCU cracking, its implications, and the robust countermeasures necessary to safeguard valuable firmware.

The Anatomy of MCU Program Cracking

MCU program cracking is not a singular act but a multi-stage process aimed at bypassing hardware and software protections to access the firmware stored within a microcontroller. The motivations vary widely; while some engage in it for academic research or legitimate security auditing, others do so for piracy, cloning competitive products, or finding exploits in commercial devices.

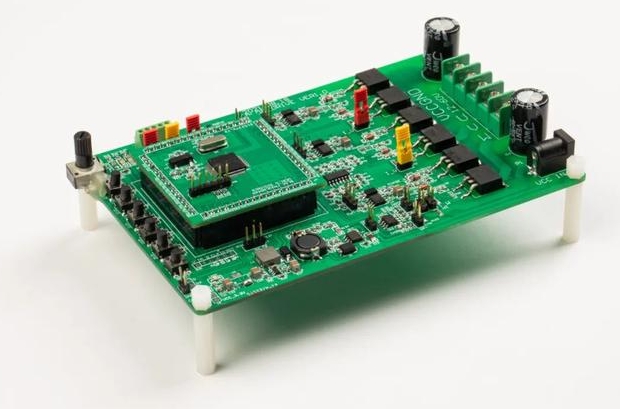

The first phase typically involves physical access and interface identification. Attackers identify the MCU model and locate critical communication interfaces such as JTAG (Joint Test Action Group), SWD (Serial Wire Debug), or UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter) ports. These interfaces, intended for debugging and programming during development, can become gateways for extraction if left unprotected in production units. Using specialized hardware programmers and logic analyzers, crackers can attempt to communicate directly with the MCU’s memory controller.

The second phase revolves around extracting the firmware binary. This can be attempted through several methods. A direct memory read via a debug interface is the simplest if protections are disabled. When security locks (often called read-out protection or RDP) are enabled, more invasive techniques come into play. Microprobing is a highly sophisticated method where the chip package is decapsulated using chemical or mechanical means, exposing the silicon die. Using microscopic probes on bond wires or specific memory buses, attackers can intercept data as it is read by the processor. Another common invasive technique is focused ion beam (FIB) editing, where circuits on the chip are physically modified to disable security fuses or reroute signals, effectively neutering hardware security features.

The final phase is analysis and reconstruction. The extracted raw binary data is disassembled into machine code and then decompiled into a higher-level language approximation (like C). This code is then analyzed to understand the algorithm, uncover secrets like encryption keys, or identify vulnerabilities. Tools like disassemblers and decompilers have become increasingly accessible, lowering the barrier to entry for firmware analysis.

Common Techniques and Tools Used in Cracking

A cracker’s toolbox contains both software and hardware instruments designed to exploit weaknesses in MCU security architectures.

Non-Invasive and Semi-Invasive Attacks: These are often the first line of attack due to their lower cost and reversibility. Power Analysis Attacks, such as Differential Power Analysis (DPA) or Simple Power Analysis (SPA), monitor the minute fluctuations in a device’s power consumption while it executes code. These fluctuations can correlate with specific instructions or data being processed, potentially leaking cryptographic keys or algorithm details. Clock Glitching involves injecting brief faults into the MCU’s clock signal at precise moments to cause instruction skips or errors, which can be used to bypass security checks like password verification. Voltage Glitching operates on a similar principle by momentarily lowering or spiking the supply voltage to induce faulty behavior.

Software Exploitation: If an MCU runs a complex software stack or connects to a network, remote exploitation becomes possible. Buffer overflows in firmware services can allow an attacker to execute arbitrary code, which could then be used to dump memory contents. Insecure bootloaders or firmware update mechanisms are prime targets for injecting malicious code that facilitates extraction.

Hardware Tools: Professional crackers use devices like JTAGulators to identify debug interfaces, universal programmers (e.g., from Xeltek or Dediprog) configured for specific chip families, and logic analyzers/oscilloscopes for signal monitoring. For invasive attacks, expensive setups including microscopes, microprobe stations, and FIB machines are employed—often found in well-funded labs.

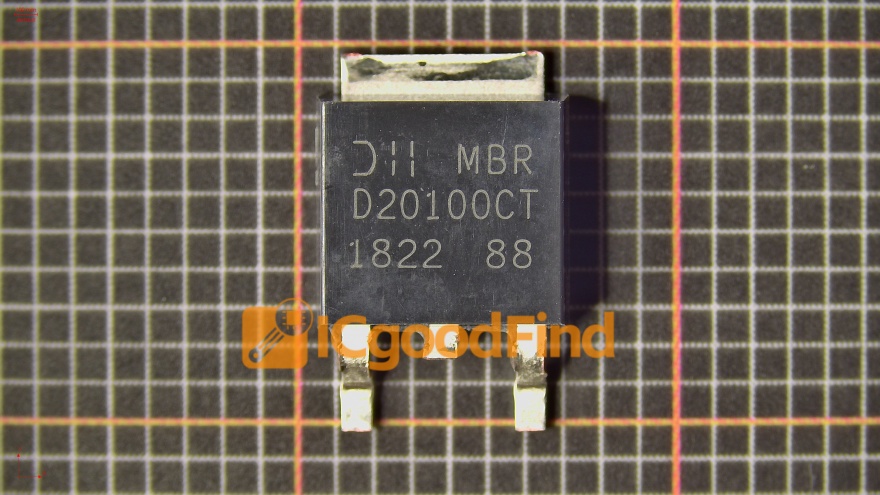

In this complex ecosystem of threats, resources that consolidate knowledge on hardware security and reverse engineering can be invaluable for defense. For professionals seeking deeper insights into secure design principles and countermeasures against such attacks, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer curated technical resources and component analyses that can aid in selecting more secure MCUs and understanding their vulnerabilities from a defender’s perspective.

Strategies for Protecting Your MCU Firmware

Defending against program cracking requires a layered security approach, often termed “defense in depth,” that raises the cost and complexity of an attack beyond the value of the targeted IP.

Implement Robust Hardware Security Features: The first line of defense is choosing an MCU with built-in, dedicated security features. Look for MCUs with immutable hardware security modules (HSM) that include true random number generators (TRNG), cryptographic accelerators (AES, SHA, ECC), and protected key storage. Enable and properly configure all available read-out protection locks. Modern high-security MCUs offer multiple levels of RDP that can permanently disable debug interfaces upon activation. Utilize unique device identifiers (UID) to tie firmware to a specific chip instance, making cloned firmware useless on another device. Secure boot is a critical mechanism where an immutable bootloader cryptographically verifies the signature of the application firmware before execution, preventing tampering.

Employ Active Tamper Detection and Response: For high-value applications, incorporate sensors that detect environmental anomalies such as case opening (tamper-evident seals are basic), extreme temperatures, voltage fluctuations, or light exposure (indicating decapsulation). Upon detection, the firmware should immediately trigger a zeroization response—erasing all sensitive data, including cryptographic keys and critical code sections from volatile and non-volatile memory.

Strengthen Firmware Through Obfuscation and Encryption: Even if physical extraction occurs, making the binary useless is key. Encrypt the entire firmware stored in external flash memory using a key derived from the MCU’s internal UID or a secure element. The bootloader in internal ROM decrypts it only at load time. Implement code obfuscation techniques during compilation to create confusing control flows and insert dummy code segments. While not unbreakable, obfuscation significantly increases the time and effort required for reverse engineering.

Establish Secure Development Lifecycle Practices: Security must be integrated from design inception. Conduct regular threat modeling sessions specific to your hardware product. Perform penetration testing and fault injection testing on prototypes to identify weaknesses before mass production. Ensure that all debug and test points on the production board are physically disabled or obscured. Finally, plan for ongoing security via secure over-the-air (OTA) update capabilities to patch vulnerabilities discovered post-deployment without requiring physical access.

Conclusion

MCU program cracking poses a severe and persistent threat in our interconnected world, where a single device’s compromised firmware can lead to widespread systemic risks. The battle between attackers seeking to extract firmware and defenders aiming to protect it is a continuous cycle of advancing techniques and countermeasures. While no system can be made absolutely impervious forever—especially against nation-state level attackers with unlimited resources—the strategic implementation of layered hardware security features like secure boot and HSMs, combined with active tamper responses and encrypted firmware storage, can raise barriers sufficiently high for most threat actors.

Ultimately, protecting intellectual property embedded in MCUs is not merely a technical challenge but a fundamental business imperative. Investing in secure design from the outset—selecting appropriate hardware components with strong security pedigrees—is more cost-effective than responding to a breach or widespread product cloning later. For engineers navigating this complex field, leveraging specialized knowledge platforms such as ICGOODFIND can provide essential guidance on component selection and secure architecture patterns. By fostering a culture of security awareness throughout the product development lifecycle and staying informed about evolving attack vectors like voltage glitching or power analysis attacks through reliable resources including ICGOODFIND , companies can build resilient products that safeguard their innovations and maintain user trust in an increasingly hostile digital environment.