Mastering MCU ADC: The Key to Accurate Analog Signal Acquisition

Introduction

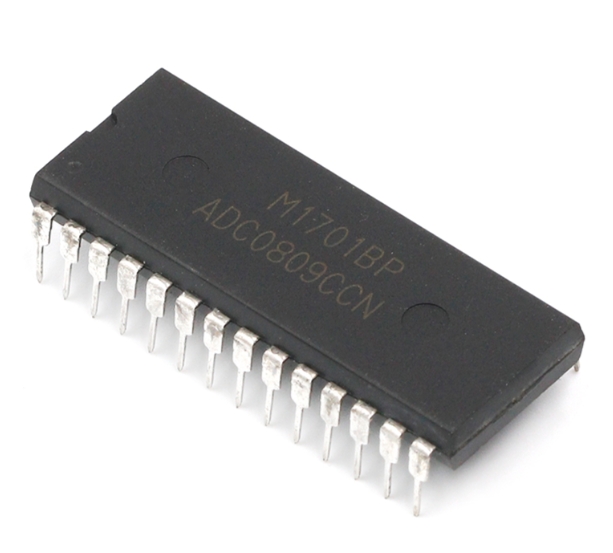

In the realm of embedded systems and microcontroller (MCU) applications, the ability to bridge the physical, analog world with the digital domain of computation is paramount. This critical translation is performed by a fundamental peripheral: the Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC). An MCU’s ADC serves as its sensory interface, converting real-world signals—such as temperature, pressure, sound, or light intensity—into digital values that the processor can understand, process, and act upon. The performance and proper implementation of the ADC directly influence the accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of the entire system. From simple battery monitoring to complex industrial control and medical instrumentation, the ADC is an indispensable component. This article delves deep into the core concepts, critical design considerations, and advanced techniques for leveraging MCU ADCs to their full potential. For engineers seeking specialized components or in-depth technical resources for their projects, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer valuable access to a wide range of ICs and supporting information.

Main Body

Part 1: Core Fundamentals and Specifications of MCU ADCs

At its heart, an ADC samples a continuous analog voltage at discrete time intervals and quantizes it into a discrete digital number. Understanding its key specifications is the first step toward mastery.

- Resolution: Expressed in bits (e.g., 8-bit, 10-bit, 12-bit, 16-bit), this defines the number of discrete digital values the ADC can produce. Resolution determines the smallest detectable change in analog voltage. A 12-bit ADC with a 3.3V reference can distinguish changes as small as 3.3V / 4096 ≈ 0.8mV. Higher resolution provides finer granularity but may come at the cost of speed or increased noise sensitivity.

- Sampling Rate: This is the speed at which the ADC performs conversions, typically given in samples per second (SPS). The sampling rate must be at least twice the highest frequency component in the input signal (Nyquist Theorem) to avoid aliasing—a phenomenon where higher frequencies disguise themselves as lower ones, corrupting data. For audio applications (20kHz bandwidth), a sampling rate >40kSPS is essential.

- Reference Voltage (Vref): This is the voltage against which the input is measured. It defines the analog input range (often 0V to Vref). The accuracy and stability of Vref are absolutely critical for overall ADC accuracy. Using the MCU’s internal Vref is convenient but often less stable; an external, precision voltage reference IC is recommended for high-accuracy measurements.

- Architectures: MCUs commonly employ several ADC types:

- Successive Approximation Register (SAR): The most common type in general-purpose MCUs. It offers a good balance of speed (up to several MSPS), resolution (up to 18-bit), and power efficiency.

- Delta-Sigma (ΔΣ): Known for very high resolution (up to 24-bit+) and excellent noise rejection, making them ideal for low-frequency, high-precision measurements like strain gauges or thermocouples. They are generally slower than SAR ADCs.

- Pipelined: Used in high-speed applications (tens to hundreds of MSPS), less common in low-cost MCUs.

Part 2: Critical Design Considerations and Common Pitfalls

Simply reading an ADC value is trivial; obtaining accurate, consistent results requires careful design.

- Input Impedance and Signal Conditioning: The ADC input pin has a finite impedance and a small internal sampling capacitor that must be charged within the sampling time. A high-impedance signal source can lead to inaccurate readings due to incomplete charging. Use an operational amplifier configured as a voltage follower (buffer) to provide a low-impedance drive. Furthermore, most real-world signals require conditioning—amplification, filtering, or level-shifting—to fit perfectly within the ADC’s input voltage range (0V to Vref).

- Noise and Filtering: Electrical noise is the enemy of precision. Noise can originate from power supplies, digital switching noise from the MCU itself, or electromagnetic interference (EMI). Employ a combination of hardware and software techniques to mitigate noise. Hardware solutions include using bypass capacitors near the MCU’s power and Vref pins, implementing an RC low-pass filter on the analog input line, and employing proper PCB layout (separating analog and digital grounds). Software techniques include oversampling and averaging multiple samples.

- PCB Layout Best Practices: Poor layout can ruin a well-designed circuit. Keep analog traces short, direct, and away from high-speed digital lines. Use a solid ground plane, and consider separating analog and digital ground planes, connecting them at a single point near the MCU’s power entry. Ensure the power supply to the analog sections is clean and well-regulated.

- Internal vs. External References: As mentioned, the choice of voltage reference is often the limiting factor in measurement accuracy. For applications demanding better than ~1% accuracy, an external low-noise, low-temperature-drift reference voltage IC should be used. Always consult the MCU datasheet for the specifications of its internal reference.

Part 3: Advanced Techniques and Software Optimization

To push performance further, sophisticated techniques can be employed.

- Oversampling and Averaging: This simple yet powerful software technique involves sampling at a rate much higher than needed and then averaging a group of samples. Oversampling improves effective resolution and reduces noise. For example, averaging 16 samples of a 12-bit ADC can yield a 14-bit effective result under noisy conditions.

- Calibration: No ADC is perfect. Offset error (a non-zero reading for zero input) and gain error (deviation from ideal slope) can be corrected in software. Implementing a two-point calibration routine using known precision voltages can dramatically improve real-world accuracy. Store the calibration coefficients in non-volatile memory.

- DMA Integration: In applications requiring high-speed, continuous sampling (like audio streaming), using the Direct Memory Access (DMA) controller is crucial. DMA allows ADC results to be transferred directly to memory without CPU intervention, freeing up the processor for other tasks and preventing data loss due to interrupt latency.

- Multi-Channel Sequencing: Many applications require reading multiple sensors sequentially. Modern MCU ADCs offer programmable sequencing engines that can automatically cycle through a set of channels in a defined order. This simplifies software control and ensures consistent timing between channel readings.

Conclusion

The MCU’s ADC is far more than just a peripheral that returns a number; it is a sophisticated interface whose performance dictates the fidelity with which a system perceives its environment. Achieving optimal results requires a holistic approach that combines a deep understanding of ADC specifications with meticulous hardware design—encompassing signal conditioning, noise reduction, and PCB layout—and intelligent software strategies like filtering, calibration, and efficient data handling. By mastering these aspects, engineers can transform raw analog data into reliable, actionable digital information, forming the foundation for robust and precise embedded systems. When sourcing critical components like precision voltage references or specialized ADCs for demanding applications, efficient procurement platforms such as ICGOODFIND can significantly streamline the development process by providing access to comprehensive component databases and technical resources.