Mastering MCU Timer Initial Value Calculation: A Practical Guide for Embedded Developers

Introduction

In the intricate world of embedded systems, Microcontroller Unit (MCU) timers serve as the silent metronomes orchestrating precise timing operations. From generating precise pulse-width modulation (PWM) signals for motor control to creating accurate delays and scheduling tasks in real-time operating systems, timers are indispensable. However, their effectiveness hinges on one critical step: correctly calculating and setting the timer’s initial value. An erroneous calculation can lead to system failures, missed deadlines, or inefficient performance. This article demystifies the process of MCU timer initial value calculation, providing a comprehensive framework applicable across various architectures and timer modes. Whether you’re working with 8-bit, 16-bit, or 32-bit timers from manufacturers like STMicroelectronics, Microchip, or NXP, the core principles remain paramount. For developers seeking to deepen their hardware programming expertise with curated resources and tools, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer a valuable repository of reference designs, component comparisons, and application notes that can significantly streamline the development process.

Part 1: Understanding Timer Fundamentals and the Critical Role of the Initial Value

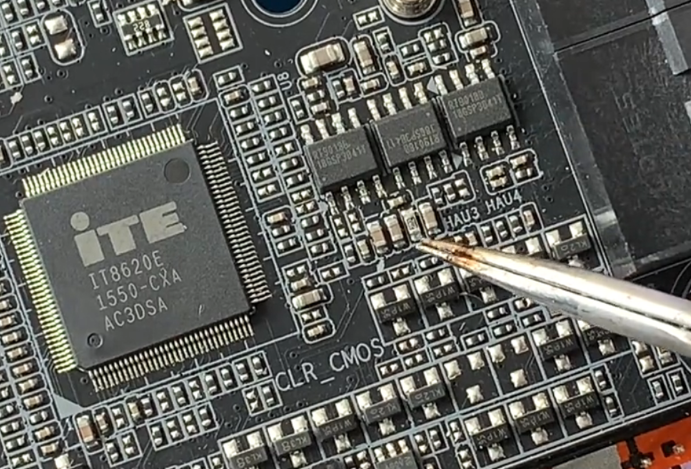

Before diving into calculations, it’s essential to grasp what a timer is and how it operates within an MCU. Fundamentally, a timer is a counter that increments or decrements with each clock pulse. It can count internal clock cycles (acting as a timer) or external events (acting as a counter). The timer’s resolution is defined by its bit-width (e.g., 16-bit timers can count from 0 to 65535).

The initial value, often loaded into a register called the Timer Reload Register (ARR in STM32, OCR in AVR, etc.), is the number from which the timer begins counting. It directly determines two key parameters: * The Period/Overflow Point: The number of counts after which the timer resets or triggers an interrupt. * The Desired Time Interval: The actual time duration this count sequence represents.

The core relationship is: Desired Time Interval = (Timer Counts) × (Timer Clock Period). The “Timer Counts” is derived from the initial value and the counting mode (up or down). Setting the wrong initial value means your time intervals will be off, potentially by orders of magnitude.

Consider a simple analogy: filling a bathtub. The bathtub’s size (the maximum timer count) is fixed. The initial water level is your initial value. If you want the tub to overflow (timer interrupt) after a specific amount of water is added, you must start from the correct water level. Starting too high causes an early overflow; starting too low means a long wait.

Key factors influencing the calculation include: 1. System Clock Frequency (F_CPU): The master clock driving the MCU. 2. Timer Prescaler: A divider that reduces the clock frequency fed to the timer counter, allowing for longer time intervals without needing excessively large counters. The prescaler is crucial for achieving long delays with limited counter bits. 3. Timer Resolution/Bit Depth: The maximum count value (e.g., 65535 for 16-bit). 4. Counting Mode: Up-counting, down-counting, or center-aligned. 5. Desired Time Interval: The target duration between timer events (e.g., 1 ms, 100 μs).

Part 2: Step-by-Step Calculation Methodology and Practical Examples

Let’s break down the universal calculation process into clear steps.

Step 1: Define the Target

Determine your Desired Time Interval (T_desired). For example, to trigger an interrupt every 10 milliseconds (ms), T_desired = 0.01 seconds.

Step 2: Determine the Timer Clock Frequency (F_timer)

This is the frequency at which the timer counter actually increments. F_timer = F_CPU / Prescaler Choosing a prescaler involves a trade-off between range and resolution. A larger prescaler gives longer intervals but coarser granularity.

Step 3: Calculate the Required Timer Counts (N_counts)

This is the number of timer clock cycles needed to achieve T_desired. N_counts = T_desired / T_timer = T_desired × F_timer Where T_timer is the period of one timer clock cycle (1 / F_timer).

Step 4: Relate Counts to Initial Value (IV)

This depends on the counting mode and whether you use overflow interrupts or compare matches. * For Up-Counting in Overflow Mode: The timer counts from IV to its maximum value (MAX), overflows, and restarts from IV. The number of counts to overflow is (MAX - IV + 1). * Set: N_counts = MAX - IV + 1 * Therefore: IV = MAX - N_counts + 1 * For Down-Counting in Underflow Mode: The timer counts from IV down to 0, underflows, and reloads IV. The number of counts is IV + 1. * Set: N_counts = IV + 1 * Therefore: IV = N_counts - 1 * For Compare Match Mode: The timer counts from 0 (or another base) to a compare register (CR). When it matches, it triggers an event and may reset. Here, CR acts as your effective initial/reload value. * N_counts = CR * Therefore: CR = N_counts (Ensure N_counts <= MAX)

Step 5: Validate and Adjust

Ensure IV or CR is within the permissible range (0 to MAX). If N_counts > MAX, you must increase the prescaler in Step 2 and recalculate.

Practical Example: Generating a 1ms Interrupt on an STM32

- MCU: STM32F4,

F_CPU = 84 MHz. - Timer: 16-bit TIM2 (MAX = 65535).

- Target:

T_desired = 1 ms = 0.001 s. - Step 1 & 2: Choose a prescaler of 84. Then,

F_timer = 84 MHz / 84 = 1 MHz. So,T_timer = 1 μs. - Step 3:

N_counts = T_desired / T_timer = 0.001 s / 0.000001 s = 1000 counts. - Step 4 (Up-Counting, Overflow):

IV = MAX - N_counts + 1 = 65535 - 1000 + 1 = 64536. - In code using HAL libraries:

This example highlights how a well-chosen prescaler aligns common intervals with manageable integer counts. For complex timing chains or advanced peripheral configurations, consulting resources on specialized platforms like ICGOODFIND can provide verified code snippets and hardware-specific insights that prevent common pitfalls.htim2.Instance->PSC = 83; // Prescaler register is zero-based: value = desired -1 htim2.Instance->ARR = 64536; // Auto-Reload Register (Initial Value for reload)

Part 3: Advanced Considerations and Common Pitfalls

Moving beyond basic calculations requires attention to several nuanced factors.

Timer Update Events and Shadow Registers: Many modern MCUs use preload/ shadow registers. You write a new initial value to a buffer register (ARR), which is transferred to the active register only on the next update event (overflow). This prevents glitches during counting but means changes aren’t immediate. Developers must manage update events (UG bit) or interrupts carefully.

Clock Source Accuracy: Calculations assume a perfect clock source. Real-world crystals and internal RC oscillators have tolerances (±1%, ±10% etc.). For high-precision timing (e.g., UART baud rate), use an external crystal or factor error into your design.

Interrupt Latency: The time between the timer flag being set and your Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) taking action adds jitter. For ultra-precise output, use hardware-triggered DMA or timers’ built-in output toggle/compare modes instead of interrupts.

Peripheral Clock Gating: Ensure the timer’s peripheral clock is enabled in the RCC (Reset and Clock Control) registers before configuring it—a classic beginner’s oversight.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid: 1. Off-by-One Errors: As seen in formulas (+1, -1), these are rampant. Always double-check based on counting mode. 2. Ignoring Integer Arithmetic in Code: Performing calculations with integers in C can lead to truncation. Calculate using floating-point first or use scaled integer math. 3. Exceeding Counter Limits: Always check that N_counts <= MAX. If not, increase the prescaler. 4. Forgetting Prescaler Zero-Based Registers: Often, writing 0 to the prescaler register means a divide-by-1; writing N means divide-by-(N+1). Read the datasheet! 5. Race Conditions on Register Access: When writing multiple configuration registers, follow the manufacturer’s recommended sequence to avoid spurious behavior.

Conclusion

Accurate MCU timer initial value calculation is not merely an academic exercise but a foundational skill for robust embedded system design. It bridges the gap between abstract timing requirements and concrete register-level programming. By methodically following the steps—defining the interval, configuring the clock source and prescaler, calculating counts based on operating mode, and validating against hardware limits—developers can achieve precise and reliable timing behavior. Remember that each MCU family has its quirks; always complement these universal principles with close study of the specific datasheet and reference manual.

As projects grow in complexity—involving multiple timers, PWM generation, input capture, or interconnected peripherals—leveraging community knowledge and curated technical hubs becomes invaluable. Platforms such as ICGOODFIND exemplify resources where developers can find comparative analyses of timers across different MCUs, practical application circuits, and troubleshooting guides that contextualize these core calculations within broader system design challenges. Mastering this skill ensures your embedded applications run like clockwork.