MCU Electronic Organ Design: A Comprehensive Guide to Modern Musical Instrument Engineering

Introduction

The fusion of music and technology has given rise to some of the most innovative instruments of our time, with the MCU-based electronic organ standing as a prime example. At its core, the design of an electronic organ revolves around a Microcontroller Unit (MCU), which acts as the digital brain, interpreting user input and generating complex audio waveforms. This technological approach has revolutionized musical accessibility, allowing for portable, feature-rich, and cost-effective instruments that rival their traditional pipe and reed counterparts. The design process is a multidisciplinary endeavor, merging principles from embedded systems engineering, digital signal processing (DSP), and human-computer interaction. This article delves deep into the critical aspects of designing an electronic organ around an MCU, exploring the hardware architecture, software algorithms, and user interface considerations that bring digital music to life. For engineers and hobbyists seeking specialized components or inspiration for such projects, platforms like ICGOODFIND can be invaluable resources for sourcing MCUs, audio codecs, and other critical electronic parts.

Main Body

Part 1: Hardware Architecture and Core Components

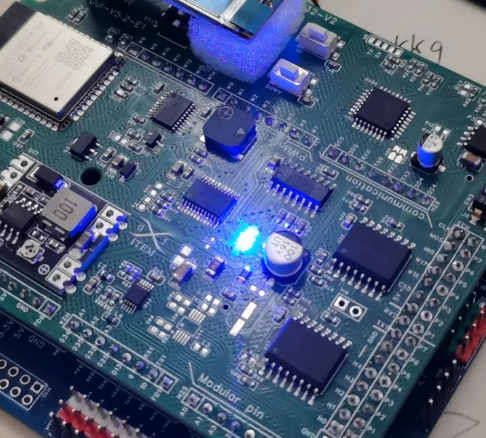

The hardware foundation of an MCU electronic organ is paramount to its performance and reliability. The design begins with the careful selection of the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) itself. Modern 32-bit ARM Cortex-M series processors (such as the STM32 or GD32 families) are often preferred due to their high clock speeds, dedicated DSP instructions, and ample memory—all essential for real-time audio synthesis. The MCU must handle multiple parallel tasks: scanning a keyboard matrix, processing control inputs, running sound generation algorithms, and managing audio output.

The keyboard interface is typically designed as a matrix to minimize the number of I/O pins required. This involves arranging the keys in rows and columns, with the MCU sequentially scanning for key presses (key-down) and releases (key-up). Debouncing circuits or algorithms are crucial here to eliminate electrical noise from mechanical key contacts. Following input detection, the heart of the sound generation lies in the audio synthesis circuitry. While some designs use the MCU’s internal DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter), for higher fidelity, an external audio codec or dedicated DAC is employed. This component converts the digital waveform generated by the MCU into an analog signal. This signal then passes through an audio amplification circuit and finally to a speaker system. Power supply design is another critical facet, requiring clean, stable voltage rails to prevent audible noise (hum) in the audio output. Furthermore, peripheral interfaces for MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), USB connectivity, or SD card storage for recording/playback are increasingly standard features, expanding the instrument’s capabilities.

Part 2: Software Algorithms and Sound Synthesis Techniques

The software embedded within the MCU is what breathes musicality into the hardware. The core challenge is generating polyphonic sound—multiple notes simultaneously—in real-time without latency. The most common synthesis method in electronic organs is wavetable synthesis. Here, high-quality samples (waveforms) of individual pipe or reed sounds are stored in ROM or flash memory. When a key is pressed, the MCU retrieves this waveform and uses a Direct Digital Synthesis (DDS) algorithm to play it back at different frequencies corresponding to the musical note. This requires precise phase accumulation and interpolation to ensure smooth pitch changes.

For more advanced or realistic organs, additive synthesis or physical modeling techniques may be implemented. Additive synthesis builds complex tones by summing multiple sine waves at different harmonics, allowing dynamic control over the organ’s “stops” (like flute, principal, or string voices). Physical modeling algorithms mathematically simulate the physics of air columns in pipes or reeds vibrating, though this is computationally intensive. All these processes run under a robust real-time operating system (RTOS) or a carefully crafted bare-metal scheduler on the MCU. This software manages tasks with strict priorities: audio generation being the highest, followed by key scanning and control updates. Implementing effects like reverberation, chorus, or vibrato digitally within the MCU further enriches the final sound. Developers often optimize these algorithms in assembly or use compiler intrinsics to leverage the MCU’s DSP capabilities fully.

Part 3: User Interface, Enclosure Design, and System Integration

The musician’s experience is shaped by the human-machine interface (HMI). Beyond the keyboard itself, this includes drawbars or tabs for voice selection (imitating traditional organ stops), potentiometers or encoders for volume and effects control, buttons for presets, and an LCD or OLED display for system feedback. The MCU must reliably read all these inputs through ADCs (for potentiometers) or digital interfaces (for encoders). The enclosure design is both an aesthetic and functional engineering task. It must house all electronics securely, provide ergonomic access to controls, and incorporate acoustically considered speaker placement. Materials choice affects durability, weight, and sound resonance.

The final stage is system integration and testing. This involves bringing together all hardware modules and software modules into a cohesive whole. Rigorous testing protocols are followed: checking for polyphonic capacity (how many notes can sound at once without degradation), measuring audio frequency response and total harmonic distortion (THD), and ensuring there is no audible latency from key press to sound output (key-to-sound latency). Power management features, such as auto-shutdown or low-power modes for battery-operated portable units, are also finalized here. For those embarking on this complex integration phase, finding reliable components is key; a platform like ICGOODFIND can streamline the procurement process for specific ICs, displays, or quality mechanical keybeds essential for a professional finish.

Conclusion

Designing an MCU-based electronic organ is a rewarding challenge that sits at the intersection of embedded systems design, digital audio engineering, and musical artistry. It requires a meticulous approach to hardware selection—prioritizing a capable MCU, clean audio pathways, and responsive input systems—coupled with sophisticated software for polyphonic sound synthesis and real-time task management. The successful integration of these elements results in an instrument that offers versatility, portability, and creative potential far beyond simple electronic keyboards. As microcontroller technology continues to advance, offering more power at lower costs, the possibilities for even more sophisticated and affordable electronic organs will expand further. Whether for educational purposes, hobbyist projects, or commercial product development, understanding these core principles of MCU Electronic Organ Design is fundamental. Engineers are encouraged to leverage comprehensive component platforms such as ICGOODFIND to source the specialized parts needed to turn schematic diagrams into harmonious reality.