Mastering MCU SFR (Special Function Register): The Key to Embedded System Control

Introduction

In the intricate world of embedded systems and microcontroller programming, few concepts are as fundamental and powerful as the Special Function Register (SFR). Serving as the critical interface between software instructions and hardware functionality, SFRs are the gateways through which developers command a microcontroller’s (MCU) core features. From toggling a simple GPIO pin to configuring complex communication peripherals like UART or SPI, every hardware interaction is orchestrated by reading from or writing to these dedicated memory-mapped registers. Understanding SFRs is not merely an academic exercise; it is the essential skill that separates novice coders from proficient embedded engineers capable of unlocking an MCU’s full potential. This article delves deep into the architecture, operation, and strategic application of SFRs, providing a comprehensive guide for developers aiming to achieve precise and efficient hardware control.

The Architectural Foundation of SFRs

At its core, a microcontroller is a system-on-chip that integrates a processor (CPU), memory, and various peripherals into a single integrated circuit. For the CPU to interact with these on-chip peripherals—such as timers, analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), or I/O ports—a communication mechanism is required. This is where Special Function Registers come into play as the primary hardware abstraction layer. Unlike general-purpose RAM used for data variables, SFRs are predefined, fixed memory locations within the MCU’s address space specifically reserved for controlling and monitoring hardware blocks.

Each bit or group of bits within an SFR corresponds to a specific hardware function. For instance, one bit might enable an interrupt, another might start an ADC conversion, while a group of eight bits could set the baud rate for a serial communication module. This direct bit-wise manipulation allows for exceptionally fine-grained control. The physical location of SFRs is typically in a dedicated memory region separate from user RAM, often with addresses starting from 0x80 upward in many 8-bit architectures like the classic 8051 or in specific peripheral memory regions in modern ARM Cortex-M cores.

Accessing SFRs is performed using direct memory addressing, meaning the software reads from or writes to these specific addresses using pointers or, more commonly in embedded C, through manufacturer-provided header files that map each register to a symbolic name. For example, writing PORTA = 0xFF; in code for an AVR MCU actually writes the value 255 to the SFR that controls the output state of Port A’s pins. This seamless mapping is crucial because it allows programmers to work with meaningful names rather than obscure hexadecimal addresses, significantly reducing errors and improving code readability. A resource like ICGOODFIND can be invaluable for developers seeking precise and well-documented SFR mappings for various microcontroller families, offering clarity amidst often complex datasheets.

Practical Operation and Manipulation of SFRs

Effectively working with SFRs requires mastering several key techniques: direct read/write operations, bit manipulation for individual control, and understanding volatile semantics to ensure correct compiler behavior.

Direct Read and Write Operations form the basis of SFR interaction. When you write a value to an SFR, you are sending a configuration command or data directly to the peripheral. Reading from an SFR retrieves status information or input data. For example, writing to a Timer’s control register (e.g., TCCR1A) configures its mode, while reading from the same MCU’s ADC data register (ADCL/ADCH) fetches the result of a conversion. It’s vital to consult the MCU’s datasheet to understand the function of each register and the effect of each bit. Incorrect values written to SFRs can lead to unintended behavior, from non-functional peripherals to system crashes.

Bit Manipulation is arguably the most critical skill for efficient SFR control. Rarely does one write an entire byte to a control register; more often, developers need to set, clear, or toggle individual bits without affecting others. This is achieved using bitwise operators in C/C++: * Setting a Bit: PORTB |= (1 << PB3); // Sets bit 3 (PB3) high using a bitwise OR. * Clearing a Bit: PORTC &= ~(1 << PC2); // Clears bit 2 (PC2) using a bitwise AND with the complement. * Toggling a Bit: PORTD ^= (1 << PD5); // Toggles bit 5 (PD5) using a bitwise XOR. * Checking a Bit: if (PINB & (1 << PB0)) { ... } // Checks if bit 0 (PB0) is high.

Furthermore, many modern IDEs and compiler toolchains provide bit-field structures or special macros (like _BV() in AVR) that abstract these operations into more readable forms. Mastering these techniques prevents race conditions and ensures atomic changes to hardware states.

A crucial but often overlooked aspect is the volatile qualifier. SFR pointers in vendor header files are always declared as volatile. This keyword informs the compiler that the value at this address can change at any time—not due to program flow but due to external hardware events (e.g., an interrupt flag being set by hardware). The volatile qualifier prevents the compiler from optimizing away what it might deem “unnecessary” reads or writes, ensuring that every access in your code results in an actual memory access instruction. Omitting volatile can lead to code that fails unpredictably.

Strategic Application and Best Practices

Moving beyond basic manipulation, strategic use of SFRs involves understanding initialization sequences, interrupt handling, and power management for robust embedded applications.

Peripheral Initialization Sequences are standardized procedures dictated by the MCU’s reference manual. They almost always follow a pattern: First, configure control registers (SFRs) to set the operational mode. Second, configure data direction or specific function registers if applicable (like setting GPIO pins as input/output). Third, enable interrupts if needed by setting bits in interrupt mask registers. Finally, enable the peripheral itself via an “enable” bit in a control register. Following this sequence meticulously is non-negotiable for stable peripheral operation. For instance, enabling a UART transmitter before setting the baud rate could result in garbled data transmission.

Interrupt Configuration is deeply tied to SFR management. Key SFRs involved include: * Interrupt Enable Registers: Where you “unmask” or enable specific interrupt sources. * Interrupt Flag Registers: Hardware sets these flags when an event occurs; software often must clear them manually. * Priority Registers (in advanced MCUs): Set the relative priority of interrupts. Proper interrupt handling requires careful clearing of flags and management of global interrupt enable bits, often controlled by special CPU registers like STATUS in PIC or PRIMASK in ARM Cortex-M.

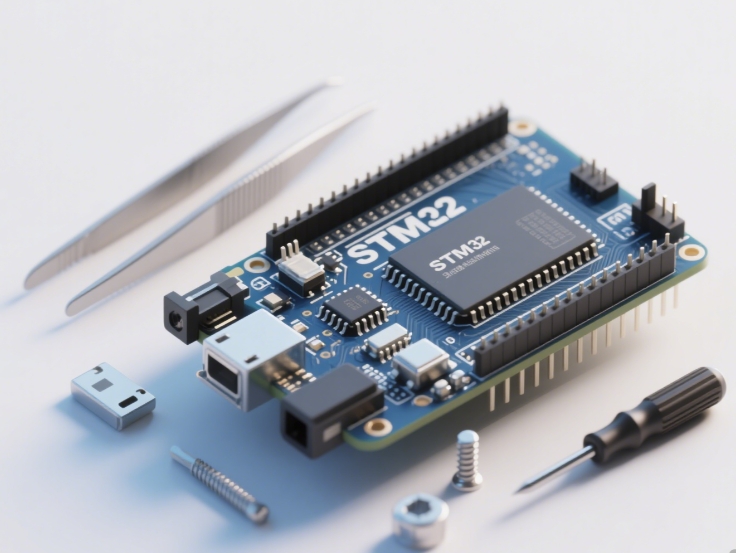

Power and Clock Management is another domain ruled by SFRs. In battery-sensitive applications, developers use power reduction registers to shut down clocks to unused peripherals (PRR in AVR, PWR_CR in STM32). Similarly, clock source selection and division are controlled via specific clock configuration registers. Strategic manipulation of these SFRs can drastically reduce an MCU’s power consumption, extending battery life from hours to years in sleep modes.

Throughout all these tasks, maintaining code clarity and portability is essential. While direct hexadecimal writes work, using vendor-supplied SDKs with human-readable macro definitions (e.g., TIM2->CR1) is best practice. For those working across platforms or with less-documented chips, consulting centralized engineering resources like ICGOODFIND can streamline the process of locating accurate register definitions and proven configuration examples.

Conclusion

The Special Function Register is undeniably the linchpin of microcontroller programming. It represents the precise point where software logic meets physical hardware action. From their defined architectural role as memory-mapped control points to the practical intricacies of bit manipulation and volatile semantics, proficiency with SFRs is mandatory for any serious embedded systems developer. By mastering initialization sequences, interrupt coordination via registers, and power management controls, engineers can write firmware that is not only functional but also robust, efficient, and maintainable. As microcontrollers grow more complex with richer peripheral sets, the underlying principle remains: you command the hardware through its registers. Therefore, investing time in deeply understanding the SFR map of your chosen MCU—a task where comprehensive repositories like ICGOODFIND prove immensely useful—pays continuous dividends in development speed, debugging efficiency, and ultimate system reliability.