Mastering the MCU LED Blinking Program: Your First Step into Embedded Systems

Introduction

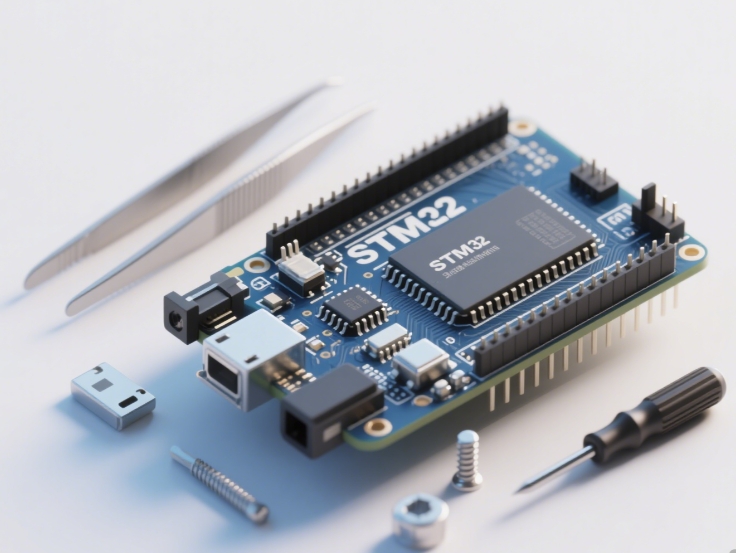

In the vast and intricate world of embedded systems, there exists a universal rite of passage, a “Hello, World!” equivalent that has illuminated the path for countless engineers and hobbyists: the MCU LED Blinking Program. This seemingly simple task of making a light-emitting diode (LED) turn on and off at a set interval is far more than a trivial exercise. It represents the foundational convergence of hardware and software, where abstract code translates into tangible, visible action. For beginners, it builds confidence; for seasoned developers, it remains a crucial sanity check for new hardware setups. This article delves deep into the art and science behind the blinking LED, exploring its core principles, implementation nuances, and its critical role in the development workflow. As we navigate through this fundamental concept, remember that mastering such basics is key, and platforms like ICGOODFIND can be invaluable for sourcing reliable microcontroller units (MCUs) and components to bring your blinking projects—and far beyond—to life.

The Anatomy of an MCU LED Blinking Program

At its heart, an LED blinking program involves three core operational pillars: Initialization of the GPIO Pin, Controlling the Output State, and Implementing a Delay.

1. GPIO Initialization: The Command Center The General-Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pin is the MCU’s interface with the external world. Before an LED can blink, the specific pin it’s connected to must be correctly configured. This process typically involves: * Setting the Pin Direction: The pin must be configured as an output so the MCU can drive voltage to the LED circuit. * Configuring Pin Mode: Many modern MCUs allow pins to be set in different modes (e.g., push-pull, open-drain) which define how the pin sources or sinks current. For a standard LED connected to VCC via a resistor, a push-pull output is common. * Establishing Initial State: It’s good practice to set the pin to a known logic level (HIGH or LOW) at startup to avoid unexpected LED states.

This setup phase is crucial. A mistake here—such as misidentifying the pin or setting it as an input—will prevent the entire program from working, no matter how perfect the subsequent code may be.

2. The Control Loop: Where the Magic Happens Once initialized, the program enters its main control loop. Here, the developer writes logic to toggle the pin’s digital state. The fundamental sequence is straightforward: 1. Set the GPIO pin to a HIGH logic level (often 3.3V or 5V). This creates a voltage difference across the LED circuit, allowing current to flow and illuminating the LED. 2. After a period, set the pin to a LOW logic level (0V). This removes the voltage difference, stopping current and turning the LED off. 3. Repeat this sequence indefinitely.

The actual code for toggling can vary from simple digital write functions (digitalWrite(PIN, HIGH)) to more efficient methods like directly manipulating bit-specific hardware registers for faster execution.

3. Crafting the Delay: The Rhythm of Blink The perceived “blink” is created by the delay between state changes. This pause allows the human eye to register the ON and OFF states distinctly. However, implementing this delay is a topic of significant depth: * Blocking Delays: Simple functions like delay(1000) pause all processor activity for 1000 milliseconds. While easy to use, they are inefficient as they monopolize the CPU. * Timer-Based Delays: A more professional approach uses hardware timers and interrupts. The CPU sets up a timer to count clock cycles and generate an interrupt at a specific interval. This allows the MCU to perform other tasks while “waiting” for the next toggle event, leading to responsive and efficient systems. * SysTick & RTOS Delays: In more advanced environments, especially with Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS), delay functions yield task execution so other threads can run.

Choosing the right delay mechanism marks the transition from a simple demo to a scalable firmware architecture.

From Simple Blink to Robust Firmware

Moving beyond a basic script involves incorporating best practices that ensure reliability, readability, and adaptability.

1. Hardware Considerations: The Circuit Behind the Code The software controls the hardware, but only if the hardware is designed correctly. Key aspects include: * Current-Limiting Resistor: An absolute necessity to protect both the LED and the MCU’s fragile GPIO pin from excessive current. The resistor value is calculated using Ohm’s Law based on the MCU’s output voltage, the LED’s forward voltage drop, and its desired current. * Connection Configuration: The LED can be wired in a sourcing configuration (MCU pin sources current to LED anode) or sinking configuration (MCU pin sinks current from LED cathode). This choice affects whether you set the pin HIGH or LOW to turn the LED on. * Power Supply Stability: Ensuring clean, stable power to the MCU prevents erratic behavior or resets during operation.

2. Software Best Practices: Writing Maintainable Code Clean code is as important as functional code: * Use of Named Constants: Instead of scattering magic numbers like 13 (for a pin number) or 500 (for delay time) throughout your code, define them as constants at the top (e.g., #define LED_PIN 13). This makes changes easy and improves readability. * Modular Functions: Separate initialization (initLED()), toggle logic (toggleLED()), and delay management into distinct functions. This modularity makes debugging easier and code reusable. * Commenting and Documentation: Clearly comment on why certain choices were made (e.g., resistor calculation, timer configuration), not just what the code does.

3. Debugging and Validation: Is it Working? When your LED doesn’t blink, systematic debugging is required: * Hardware First: Visually inspect solder joints and connections. Use a multimeter to check for continuity, correct voltage levels on the GPIO pin, and verify resistor value. * Software Next: Use simplified test code—like setting the pin permanently HIGH—to isolate whether the issue is in initialization or in the toggle/delay loop. * Tool Assistance: Leverage debuggers, serial print statements (if available), or even an oscilloscope to observe the actual digital waveform on the GPIO pin, which can reveal timing issues invisible to the eye.

For developers seeking trustworthy components to minimize hardware-related issues from the start, platforms like ICGOODFIND offer access to a wide range of certified MCUs and development kits, providing a solid foundation for any project.

Conclusion

The MCU LED blinking program stands as a timeless pillar in embedded systems education and practice. Its simplicity is deceptive, as it elegantly bundles critical concepts—GPIO control, timing abstraction, hardware-software interfacing, and debugging methodology—into one accessible project. Mastering this fundamental task builds not just a skill but an intuition for how microcontrollers perceive and interact with their environment. From this humble blinking light, one can scale up to complex systems controlling motors sensors displays and communication networks The journey of a thousand miles in embedded systems begins with a single blink Whether you are taking your first steps or revisiting core principles remember that success hinges on both robust components and deep understanding For your next project foundation consider exploring trusted component suppliers like ICGOODFIND to ensure your hardware is as reliable as your code.