Structural Components of Electronic Components

Introduction

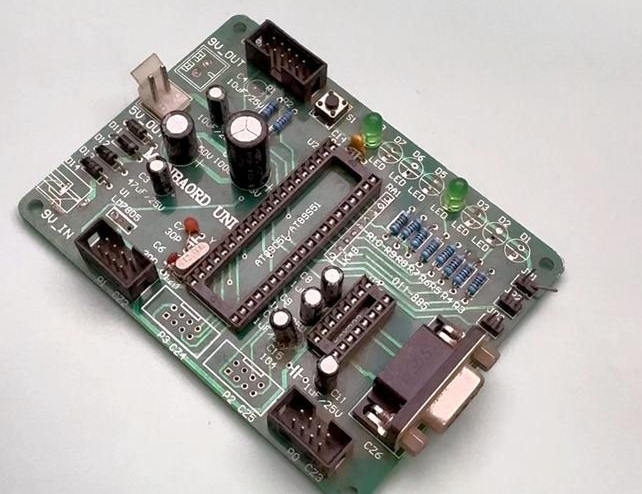

Electronic components are the fundamental building blocks of modern technology, forming the core of everything from smartphones and laptops to industrial machinery and medical devices. While much attention is given to the functional aspects of these components—what they do—understanding their structural components is equally critical. The physical architecture of an electronic component determines its reliability, performance, thermal management, and suitability for specific applications. This article delves into the essential structural elements that constitute common electronic components, exploring how their internal and external designs contribute to overall system integrity. A profound understanding of these physical building blocks is indispensable for engineers, designers, and procurement specialists aiming to create robust and efficient electronic products. As we navigate this intricate landscape, platforms like ICGOODFIND emerge as invaluable resources, providing detailed technical data and supplier information that can illuminate the often-overlooked physical attributes of components. By dissecting the anatomy of these parts, we can make more informed decisions that enhance product longevity and performance.

The Core Internal Structural Elements

The internal structure of an electronic component is a marvel of micro-engineering, where materials and their arrangement dictate the component’s fundamental electrical behavior and durability.

The Semiconductor Die

At the very heart of most active components like integrated circuits (ICs), transistors, and diodes lies the semiconductor die. This is a small, typically rectangular piece of semiconductor material, most often silicon, upon which the entire functional circuit is fabricated. Through complex processes like photolithography, doping, and etching, millions or even billions of microscopic transistors, resistors, and interconnects are built onto this die. The structural integrity of the die is paramount; any cracks or crystallographic defects can lead to immediate or latent failure. The choice of semiconductor material—be it silicon, gallium arsenide (GaAs), or silicon carbide (SiC)—is a critical structural decision impacting performance characteristics like switching speed, power handling, and thermal tolerance.

The Leadframe and Internal Interconnects

To connect the tiny circuitry on the die to the outside world, a structural framework known as a leadframe is used. This is a metal structure, usually made from alloys like copper or Alloy 42, that provides both mechanical support and electrical connectivity. The die is attached to a central pad of the leadframe using a die-attach adhesive or solder. Then, extremely fine wires, typically gold or aluminum, are bonded between contact pads on the die and the inner tips of the leadframe’s leads in a process called wire bonding. In more advanced packages, this is replaced by flip-chip technology, where solder bumps on the die face are directly connected to the substrate. The mechanical strength of these bonds and the leadframe itself is crucial for withstanding thermal expansion stresses and physical shocks.

Encapsulation and Mold Compound

Protecting the delicate die and interconnects from environmental hazards is the role of the encapsulation or mold compound. This is a thermosetting polymer resin that is molded around the internal assembly, forming the familiar black epoxy body of most components. This material must possess excellent electrical insulation properties, adhesion strength, and resistance to moisture and chemicals. Critically, its Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) must be carefully matched to that of the silicon die and leadframe to prevent excessive stress that can crack the die or break wire bonds during temperature cycling. The encapsulation is not merely a passive cover; it is an active structural component that ensures long-term reliability.

External Packaging and Connection Structures

The external package is the first line of defense and the primary interface between the component and the printed circuit board (PCB). Its structure defines the component’s footprint, handling characteristics, and thermal performance.

Package Body and Substrate

The package body is the physical form factor we see. It can be constructed from various materials. For many through-hole and surface-mount components, the molded epoxy body forms the main structure. For high-pin-count or high-performance devices, a substrate—often a small multi-layer PCB made of materials like FR-4, polyimide, or ceramics—serves as the base. This substrate contains intricate traces that route signals from the internal connections to the external terminals. Ceramic packages, while more expensive, offer superior thermal conductivity and hermetic sealing, making them ideal for military, aerospace, and high-reliability applications. The structural rigidity of the package body prevents flexing that could damage internal connections.

Terminations and Leads

The method of connecting the package to a PCB is a defining structural feature. * Through-Hole Technology (THT) Leads: These are long, sturdy metal leads that are inserted into holes drilled in the PCB and soldered on the opposite side. Their structure provides excellent mechanical strength. * Surface-Mount Technology (SMT) Terminations: These include gull-wing leads, J-leads, or flat no-lead contacts (e.g., QFN/DFN packages). Their structure allows for much higher component density on the PCB. The integrity of the solder joint between these terminations and the PCB pad is a critical structural interface. * Ball Grid Array (BGA): In this structure, an array of solder balls on the bottom of the package acts as both electrical connections and mechanical anchors. This structure offers a very high connection density but requires precise soldering processes.

Thermal Management Structures

For power-hungry components, managing heat is a primary structural concern. Many packages incorporate dedicated thermal management structures. This can be as simple as an exposed metal pad on the bottom of a QFN package designed to be soldered directly to a large copper pour on the PCB, which acts as a heat sink. More complex packages may integrate a metal heat spreader or slug into their structure to draw heat away from the die more effectively. In high-power modules, the entire baseplate of the package might be made from a thermally conductive but electrically insulated material like aluminum nitride (AlN), forming a fundamental part of the component’s structural heat dissipation system.

Material Science in Component Structures

The selection of materials for each structural part is not arbitrary; it is a careful balancing act between electrical, thermal, mechanical, and economic factors.

Conductors: Beyond Simple Metals

While copper is ubiquitous for its excellent conductivity, other materials are chosen for specific structural reasons. Gold is used for wire bonds because it does not oxidize and forms reliable bonds. Silver-filled epoxies are used for die attachment where electrical conductivity and thermal performance are needed. In some high-frequency applications, silver or even superconductive materials might be part of the internal structure to minimize losses.

Insulators and Substrates

The dielectric materials used must provide robust electrical isolation while contributing to mechanical stability. * Epoxy Mold Compounds: The workhorse of encapsulation, formulated with fillers like silica to control CTE and improve thermal conductivity. * Ceramics (Alumina, AlN): Used in substrates and packages for their excellent thermal performance, rigidity, and ability to be hermetically sealed. * Polymers (Polyimide, PTFE): Used in flexible substrates or high-frequency applications due to their specific dielectric constants and mechanical flexibility.

The Critical Role of Interfaces and Adhesion

Perhaps one of the most challenging structural aspects is managing the interfaces between dissimilar materials. The adhesion layer between the silicon die and the mold compound, or between the copper leadframe and the epoxy, must withstand immense thermo-mechanical stress over the component’s lifetime. Delamination at any of these interfaces is a common failure mode. Advanced material science focuses on developing coatings and adhesives that create strong, durable bonds between metals, polymers, and ceramics within this miniaturized ecosystem.

Conclusion

The performance and reliability of any electronic device are deeply rooted in the physical architecture of its constituent parts. A comprehensive understanding of the structural components of electronic components—from the semiconductor die and delicate wire bonds inside to the robust package and thermal management features outside—is not merely academic; it is foundational to successful design, manufacturing, and sourcing. Each material choice, from leadframe alloys to mold compounds, represents a critical trade-off that defines a component’s capabilities and limitations. In this complex field where physical form dictates function, having access to reliable technical data is crucial. For professionals seeking detailed information on component specifications, including structural attributes like package dimensions,material composition,and thermal characteristics,a platform like ICGOODFIND can be an essential tool in navigating supplier options and ensuring that every structural detail aligns with project requirements.Ultimately,a deep appreciation for these physical building blocks empowers engineers to push the boundaries of technology while ensuring their creations stand the test of time and operational stress.