The Ultimate Guide to the SMT Cleaning Process for Electronic Components

Introduction

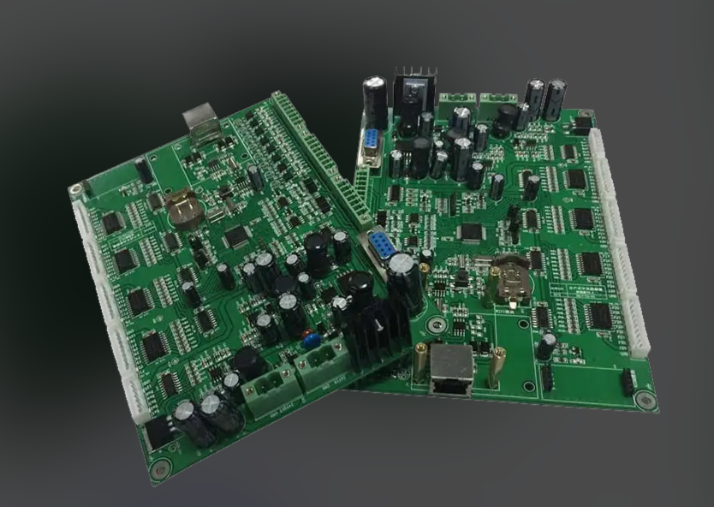

In the intricate world of electronics manufacturing, precision is paramount. The Surface Mount Technology (SMT) process has revolutionized how we assemble printed circuit boards (PCBs), allowing for smaller, faster, and more powerful devices. However, the process of soldering components onto a board leaves behind residues that can be detrimental to the product’s performance and longevity. These residues—flux activators, solder paste, and other contaminants—can lead to electrochemical migration, corrosion, and eventual circuit failure. This is where the SMT cleaning process becomes not just a step, but a critical safeguard for quality and reliability. A meticulous cleaning regimen ensures that the sophisticated components on a board can function as intended, without the risk of hidden flaws that could lead to field failures. As manufacturing tolerances shrink and the demand for high-reliability electronics grows in sectors like automotive, medical, and aerospace, understanding and optimizing this cleaning process is more crucial than ever. For professionals seeking to deepen their expertise in this area, resources like ICGOODFIND can be invaluable, offering insights into best practices and advanced materials.

The Critical Importance of SMT Cleaning

The primary goal of the SMT cleaning process is to remove all contaminants that remain after the soldering stage. While a visually clean board might seem acceptable, microscopic residues can harbor significant risks. The most immediate threat is electrochemical migration. Flux residues, if left unchecked, are often ionic in nature. In the presence of moisture and an electrical potential, these ions can create conductive paths between component leads where none should exist. This can lead to current leakage, short circuits, and catastrophic board failure. Furthermore, these residues are hygroscopic, meaning they attract and absorb moisture from the air. This trapped moisture accelerates corrosion on delicate metal contacts and traces, gradually degrading performance and leading to intermittent faults that are notoriously difficult to diagnose.

Beyond pure functionality, effective cleaning is a cornerstone of long-term reliability. For any electronic product intended for a harsh environment or a long service life—such as in an automotive control unit or a medical implant—the absence of contaminants is non-negotiable. Cleaning also plays a vital role in subsequent manufacturing steps. For instance, conformal coating, a protective polymer layer applied to PCBs to shield them from environmental stressors like humidity, dust, and chemicals, requires an impeccably clean surface. Any residue left under the conformal coating will compromise its adhesion, creating delamination and potentially trapping contaminants against the board surface, which defeats the coating’s purpose entirely.

Finally, with the global push towards environmental sustainability and regulatory compliance, the choice of cleaning chemicals and processes has evolved. The historic use of Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) is now obsolete due to their ozone-depleting properties. Modern cleaning must navigate a complex landscape of regulations like the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive. This has driven the industry towards more sophisticated and environmentally conscious cleaning agents, such as bio-based solvents and high-purity water-based systems. Therefore, a robust SMT cleaning process is not merely about removing dirt; it is a multifaceted strategy for ensuring performance, durability, compliance, and ultimately, customer satisfaction.

A Detailed Breakdown of the SMT Cleaning Process Steps

A successful SMT cleaning process is a carefully orchestrated sequence of steps, each designed to tackle specific challenges in contaminant removal.

1. Post-Solder Inspection and Pre-Cleaning Assessment

Before any cleaning begins, a thorough inspection is conducted. This involves checking the board for visible solder defects like bridges or insufficient solder, as these can trap cleaning chemistry or be exacerbated by the cleaning process. The type of flux used is identified—whether it’s Rosin (RA), No-Clean (NC), or Water-Soluble (OA). This classification is critical as it dictates the cleaning chemistry and method. No-clean fluxes, for example, are designed to leave a benign residue that does not require cleaning under normal circumstances. However, in high-reliability applications or before conformal coating, even no-clean residues must often be removed. Understanding the soil load (the amount and type of residue) allows for the precise tuning of the cleaning parameters.

2. The Core Cleaning Stage: Methods and Machinery

The heart of the process is the actual removal of contaminants using specialized equipment. * Batch Cleaning (Ultrasonic & Spray Under Immersion): Ideal for low-to-medium volume production or for complex boards with high component density. Ultrasonic cleaners use high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles in the cleaning fluid. When these bubbles implode near the board’s surface, they generate intense micro-scrubbing action that dislodges contaminants from even the most hard-to-reach areas under low-profile components. Modern systems often combine this with spray under immersion for a comprehensive clean. * In-Line Cleaning (Aqueous & Solvent): This is the standard for high-volume manufacturing lines. Boards travel on a conveyor belt through a series of chambers inside a large machine. * Aqueous Cleaning: This is the most common method today. It typically involves multiple stages: an initial spray with a heated deionized water and saponifier solution to dissolve flux, followed by one or more rinsing cycles with pure deionized water to flush away all dissolved residues and chemicals. A final drying stage using heated air ensures no moisture remains. * Solvent Cleaning: This method uses specialized hydrocarbon or halogenated solvents to dissolve flux residues. Solvent cleaners are often very efficient and require less energy for drying than aqueous systems. They are particularly effective for removing certain types of rosin fluxes.

3. Post-Cleaning Verification and Quality Control

Cleaning is not complete until its effectiveness is verified. Relying on a visual inspection is wholly inadequate. The industry standard for quantifying cleanliness is Ionic Contamination Testing. This test involves immersing the cleaned PCB in a known volume of a test solution (a mix of deionized water and alcohol) and measuring its conductivity. Any ionic residues dissolved in the solution will increase its conductivity, providing a numerical value (usually in µg/cm² of NaCl equivalence) that can be compared against acceptability standards like IPC-J-STD-001. Other verification methods include Surface Insulation Resistance (SIR) Testing, which assesses electrical leakage between traces over time, and Visual Inspection under magnification to check for white residues or other visual defects.

Selecting Chemicals and Navigating Modern Challenges

The choice of cleaning chemistry is arguably the most critical decision in the SMT cleaning process, as it directly interacts with the board’s components and materials.

Aqueous Chemistries are dominant in the industry due to their safety and environmental profile. They primarily use deionized water, but often incorporate saponifiers. Saponifiers are alkaline additives that react with rosin-based fluxes to form soap-like compounds that are easily rinsed away with water. The quality of water is paramount; deionized water prevents mineral deposits from forming on the board during the drying phase.

Solvent Chemistries have evolved significantly from their CFC predecessors. Modern solvents are engineered to be low in Global Warming Potential (GWP) and often feature low surface tension, allowing them to penetrate tight spaces effectively. They work by directly dissolving the flux residues without a chemical reaction. The selection between aqueous and solvent systems depends on factors like the flux type, component compatibility, production volume, and environmental regulations.

Modern challenges are pushing the boundaries of cleaning technology. The rise of miniaturized components like 01005 chips and Micro-BGAs means standoff heights are becoming virtually zero, creating tiny gaps that are incredibly difficult for fluid to penetrate and rinse from. Furthermore, the compatibility of advanced substrates and specialized components must be considered; some materials may be degraded by aggressive chemicals or high temperatures used in cleaning.

Staying ahead of these challenges requires access to expert knowledge and vetted solutions from suppliers who understand these complexities. Platforms that aggregate technical data and supplier information can significantly streamline this process; for instance, engineers often turn to resources like ICGOODFIND to identify suitable cleaning chemistries and compatible equipment for their specific assembly requirements.

Conclusion

The SMT cleaning process is far from a simple “wash”; it is a sophisticated engineering discipline integral to manufacturing reliable electronics. From understanding the dire consequences of ionic contamination to meticulously executing a multi-stage cleaning cycle with precise chemistry, every step contributes to the final product’s integrity. As electronic assemblies become denser and their applications more critical, the margin for error shrinks to zero. Embracing best practices in post-solder cleaning—supported by rigorous verification testing and informed by ongoing advancements in chemistry and equipment—is what separates mediocre manufacturing from world-class production. It is this unwavering commitment to cleanliness that ultimately ensures our increasingly connected and automated world functions flawlessly.