MCU Power-On: A Comprehensive Guide to Reliable Microcontroller Startup

Introduction

In the intricate world of embedded systems, few moments are as critical—and as potentially fraught with challenges—as the moment a microcontroller (MCU) powers on. The MCU Power-On sequence is the foundational process that transitions a chip from an inert piece of silicon to a functional, programmable brain. This initial burst of activity sets the stage for all subsequent operations, making its reliability paramount. A flawed power-on routine can lead to erratic behavior, boot failures, or even permanent hardware damage, jeopardizing entire systems from medical devices to automotive controls. Understanding this process is not merely an academic exercise; it is an essential engineering discipline for ensuring robust and predictable device operation. This article delves deep into the mechanics, challenges, and best practices of the MCU power-on sequence, providing a roadmap for developers to achieve flawless startup every time.

The Anatomy of an MCU Power-On Sequence

The power-on sequence is a meticulously orchestrated series of hardware and software events. It is far more complex than simply applying voltage.

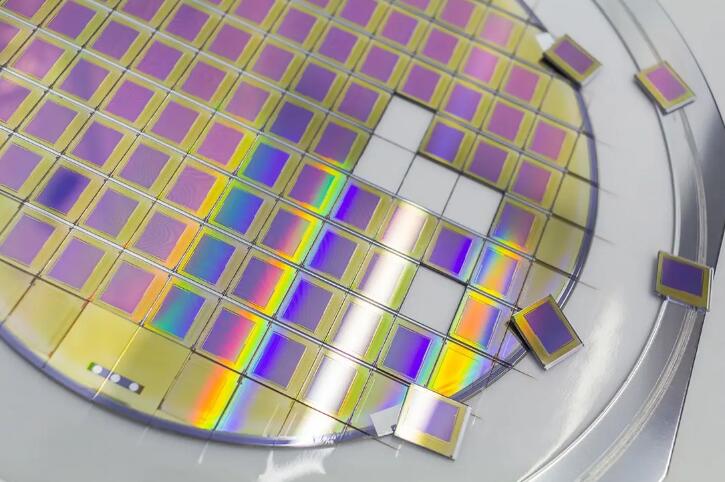

1. The Physical Layer: Power Ramp and Stabilization The journey begins when voltage is applied to the MCU’s power supply pins (VDD, VCC). The rate of voltage rise (dV/dt) is a critical first factor. An excessively slow ramp can cause the MCU to linger in an undefined state, potentially leading to high leakage currents or latch-up. Conversely, a very fast ramp might induce voltage spikes or ringing due to board parasitics. Most MCU datasheets specify a minimum and maximum rise time for the core voltage. Following the initial ramp, the power supply must reach and stabilize within the MCU’s specified operating range (e.g., 1.8V ±5% or 3.3V ±10%). During this period, the internal circuitry remains in a reset state, often held there by a dedicated Power-On Reset (POR) circuit.

2. The Core Initialization: Clock, Reset, and Bootloaders Once the supply voltage is stable and the POR circuit releases its hold, the MCU core awakens in a known state. The first task is often to initialize the internal clock source. Many MCUs start with a low-power internal RC oscillator before potentially switching to a more precise external crystal. Simultaneously, critical registers are set to their default reset values. The processor then fetches its initial instruction from a predefined memory address, typically the reset vector. This address points to the beginning of the bootloader—a small piece of firmware permanently stored in protected memory (like ROM or a protected flash sector). The bootloader’s job is to handle basic system checks and ultimately load the main application code into executable memory. In some architectures, it may also manage firmware updates.

3. The Software Handoff: From Startup Code to main() Before reaching the familiar main() function of your C application, the MCU executes vital startup code (often provided by the toolchain as a file like startup.s). This code performs low-level initialization that the high-level language cannot, such as: * Initializing the Stack Pointer: Setting up memory for function calls and interrupts. * Zero-initializing the .bss section: Clearing global and static variables set to zero. * Copying initialized data: Moving non-constant initialized variables from flash (.data section) to their designated locations in RAM. * Calling static constructors: In C++, executing code before main(). Only after this meticulous setup is complete does the program counter jump to the main() function, marking the successful conclusion of the power-on sequence and the beginning of application control.

Critical Challenges and Pitfalls in Power-On Design

Designing for a reliable power-on is about anticipating and mitigating failure points.

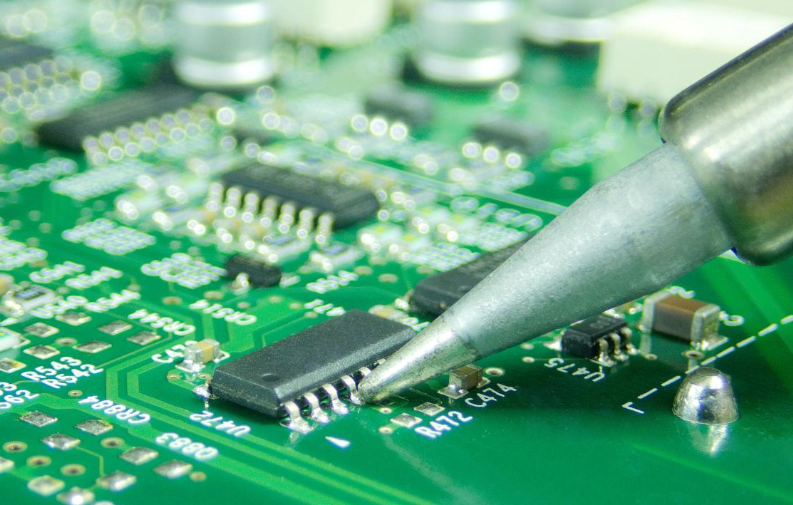

1. Power Supply Integrity and Sequencing In modern systems with multiple voltage rails (e.g., core voltage, I/O voltage, analog voltage), proper power sequencing is non-negotiable. Applying I/O voltage before the core voltage can cause unintended current flows through protection diodes, damaging the chip. Designers must adhere strictly to the sequence recommended in the datasheet, using dedicated power management ICs (PMICs) or carefully designed RC delay networks if necessary. Furthermore, decoupling capacitors must be placed as close as possible to MCU power pins to filter high-frequency noise and provide instantaneous current during the initial surge. Insufficient or poorly placed decoupling is a common root cause of unstable startups.

2. Reset Circuit Design and Timing The reset signal must remain asserted long enough after power stabilization to ensure all internal logic is ready. While most MCUs have an internal POR circuit, these often have minimum supply voltage thresholds that may not cover all brown-out scenarios. Therefore, using an external supervisor IC or a well-designed RC reset circuit is considered a best practice. These external circuits provide a predictable reset pulse width and can monitor for brown-out conditions below the internal POR’s threshold. A common mistake is neglecting the reset line’s susceptibility to noise, which can cause spurious resets; proper PCB layout and sometimes a small filter capacitor are essential.

3. Unstable Clock Sources and Faulty Boot Configuration The clock is the heartbeat of the MCU. If an external crystal or resonator fails to start oscillating reliably—due to incorrect load capacitors, poor PCB layout, or excessive stray capacitance—the MCU may hang during startup. Ensuring the oscillator circuit matches the MCU manufacturer’s guidelines is crucial. Another critical hardware aspect is correctly setting boot configuration pins. These pins (or their software equivalents in OTP memory) tell the MCU where to find its first instruction—from internal flash, external memory, or a serial bootloader. Incorrect configuration here leads to an immediate boot failure.

Best Practices for Ensuring Robust MCU Startup

Achieving “five-nines” reliability starts at power-on.

1. Meticulous Schematic and Layout Adherence Treat the MCU manufacturer’s reference design as your baseline. Follow their recommendations for power network design, decoupling, oscillator circuits, and reset circuitry exactly. Pay special attention to grounding schemes; use a solid ground plane and ensure star points for analog and digital grounds if required. High-frequency and sensitive traces (like clock lines) should be kept short and away from noisy switching lines.

2. Implementing Comprehensive Watchdog Strategies A watchdog timer (WDT) is your last line of defense against a failed startup that leaves the system in a hung state. Enable an independent watchdog timer (IWDT) as early as possible in your startup code, ideally before complex initializations begin. This ensures that if code execution stalls before main() is reached, a hardware reset will be triggered to restart the entire sequence.

3. Strategic Diagnostic Software in Startup Code Don’t treat startup code as a “set-and-forget” black box. Embed strategic diagnostics: * Test RAM integrity early using patterns like checkerboard or walking-bit tests. * Verify critical data paths, such as confirming that data copied from flash to RAM is correct via checksums. * Initialize communication peripherals (like UART) early to output status codes or error messages during development—a practice known as “bring-up debugging.” For engineers seeking advanced diagnostic tools and components that aid in robust system design—from reliable PMICs to sophisticated debug probes—resources like ICGOODFIND can be invaluable for identifying optimal solutions tailored for challenging power management and initialization scenarios.

Conclusion

The MCU power-on sequence is a deceptively complex symphony of electrical signals and firmware instructions where precision dictates reliability. From ensuring clean and properly sequenced power rails to designing foolproof reset circuits and writing defensive startup code, every detail contributes to that crucial first impression your embedded system makes upon waking up. By moving beyond a superficial understanding and embracing a holistic view of this process—addressing challenges in hardware design, timing analysis, and software initialization—developers can build systems that not only start correctly every time but also possess a foundational resilience against real-world electrical noise and anomalies. In an era where microcontrollers govern increasingly critical aspects of our lives, mastering their very first moment of operation is not just good engineering; it is an absolute necessity.